- Google Slides Presentation Design

- Pitch Deck Design

- Powerpoint Redesign

- Other Design Services

- Guide & How to's

- How to present a research paper in PPT: best practices

A research paper presentation is frequently used at conferences and other events where you have a chance to share the results of your research and receive feedback from colleagues. Although it may appear as simple as summarizing the findings, successful examples of research paper presentations show that there is a little bit more to it.

In this article, we’ll walk you through the basic outline and steps to create a good research paper presentation. We’ll also explain what to include and what not to include in your presentation of research paper and share some of the most effective tips you can use to take your slides to the next level.

Research paper PowerPoint presentation outline

Creating a PowerPoint presentation for a research paper involves organizing and summarizing your key findings, methodology, and conclusions in a way that encourages your audience to interact with your work and share their interest in it with others. Here’s a basic research paper outline PowerPoint you can follow:

1. Title (1 slide)

Typically, your title slide should contain the following information:

- Title of the research paper

- Affiliation or institution

- Date of presentation

2. Introduction (1-3 slides)

On this slide of your presentation, briefly introduce the research topic and its significance and state the research question or objective.

3. Research questions or hypothesis (1 slide)

This slide should emphasize the objectives of your research or present the hypothesis.

4. Literature review (1 slide)

Your literature review has to provide context for your research by summarizing relevant literature. Additionally, it should highlight gaps or areas where your research contributes.

5. Methodology and data collection (1-2 slides)

This slide of your research paper PowerPoint has to explain the research design, methods, and procedures. It must also Include details about participants, materials, and data collection and emphasize special equipment you have used in your work.

6. Results (3-5 slides)

On this slide, you must present the results of your data analysis and discuss any trends, patterns, or significant findings. Moreover, you should use charts, graphs, and tables to illustrate data and highlight something novel in your results (if applicable).

7. Conclusion (1 slide)

Your conclusion slide has to summarize the main findings and their implications, as well as discuss the broader impact of your research. Usually, a single statement is enough.

8. Recommendations (1 slide)

If applicable, provide recommendations for future research or actions on this slide.

9. References (1-2 slides)

The references slide is where you list all the sources cited in your research paper.

10. Acknowledgments (1 slide)

On this presentation slide, acknowledge any individuals, organizations, or funding sources that contributed to your research.

11. Appendix (1 slide)

If applicable, include any supplementary materials, such as additional data or detailed charts, in your appendix slide.

The above outline is just a general guideline, so make sure to adjust it based on your specific research paper and the time allotted for the presentation.

Steps to creating a memorable research paper presentation

Creating a PowerPoint presentation for a research paper involves several critical steps needed to convey your findings and engage your audience effectively, and these steps are as follows:

Step 1. Understand your audience:

- Identify the audience for your presentation.

- Tailor your content and level of detail to match the audience’s background and knowledge.

Step 2. Define your key messages:

- Clearly articulate the main messages or findings of your research.

- Identify the key points you want your audience to remember.

Step 3. Design your research paper PPT presentation:

- Use a clean and professional design that complements your research topic.

- Choose readable fonts, consistent formatting, and a limited color palette.

- Opt for PowerPoint presentation services if slide design is not your strong side.

Step 4. Put content on slides:

- Follow the outline above to structure your presentation effectively; include key sections and topics.

- Organize your content logically, following the flow of your research paper.

Step 5. Final check:

- Proofread your slides for typos, errors, and inconsistencies.

- Ensure all visuals are clear, high-quality, and properly labeled.

Step 6. Save and share:

- Save your presentation and ensure compatibility with the equipment you’ll be using.

- If necessary, share a copy of your presentation with the audience.

By following these steps, you can create a well-organized and visually appealing research paper presentation PowerPoint that effectively conveys your research findings to the audience.

What to include and what not to include in your presentation

In addition to the must-know PowerPoint presentation recommendations, which we’ll cover later in this article, consider the following do’s and don’ts when you’re putting together your research paper presentation:

- Focus on the topic.

- Be brief and to the point.

- Attract the audience’s attention and highlight interesting details.

- Use only relevant visuals (maps, charts, pictures, graphs, etc.).

- Use numbers and bullet points to structure the content.

- Make clear statements regarding the essence and results of your research.

Don’ts:

- Don’t write down the whole outline of your paper and nothing else.

- Don’t put long, full sentences on your slides; split them into smaller ones.

- Don’t use distracting patterns, colors, pictures, and other visuals on your slides; the simpler, the better.

- Don’t use too complicated graphs or charts; only the ones that are easy to understand.

- Now that we’ve discussed the basics, let’s move on to the top tips for making a powerful presentation of your research paper.

8 tips on how to make research paper presentation that achieves its goals

You’ve probably been to a presentation where the presenter reads word for word from their PowerPoint outline. Or where the presentation is cluttered, chaotic, or contains too much data. The simple tips below will help you summarize a 10 to 15-page paper for a 15 to 20-minute talk and succeed, so read on!

Tip #1: Less is more

You want to provide enough information to make your audience want to know more. Including details but not too many and avoiding technical jargon, formulas, and long sentences are always good ways to achieve this.

Tip #2: Be professional

Avoid using too many colors, font changes, distracting backgrounds, animations, etc. Bullet points with a few words to highlight the important information are preferable to lengthy paragraphs. Additionally, include slide numbers on all PowerPoint slides except for the title slide, and make sure it is followed by a table of contents, offering a brief overview of the entire research paper.

Tip #3: Strive for balance

PowerPoint slides have limited space, so use it carefully. Typically, one to two points per slide or 5 lines for 5 words in a sentence are enough to present your ideas.

Tip #4: Use proper fonts and text size

The font you use should be easy to read and consistent throughout the slides. You can go with Arial, Times New Roman, Calibri, or a combination of these three. An ideal text size is 32 points, while a heading size is 44.

Tip #5: Concentrate on the visual side

A PowerPoint presentation is one of the best tools for presenting information visually. Use graphs instead of tables and topic-relevant illustrations instead of walls of text. Keep your visuals as clean and professional as the content of your presentation.

Tip #6: Practice your delivery

Always go through your presentation when you’re done to ensure a smooth and confident delivery and time yourself to stay within the allotted limit.

Tip #7: Get ready for questions

Anticipate potential questions from your audience and prepare thoughtful responses. Also, be ready to engage in discussions about your research.

Tip #8: Don’t be afraid to utilize professional help

If the mere thought of designing a presentation overwhelms you or you’re pressed for time, consider leveraging professional PowerPoint redesign services . A dedicated design team can transform your content or old presentation into effective slides, ensuring your message is communicated clearly and captivates your audience. This way, you can focus on refining your delivery and preparing for the presentation.

Lastly, remember that even experienced presenters get nervous before delivering research paper PowerPoint presentations in front of the audience. You cannot know everything; some things can be beyond your control, which is completely fine. You are at the event not only to share what you know but also to learn from others. So, no matter what, dress appropriately, look straight into the audience’s eyes, try to speak and move naturally, present your information enthusiastically, and have fun!

If you need help with slide design, get in touch with our dedicated design team and let qualified professionals turn your research findings into a visually appealing, polished presentation that leaves a lasting impression on your audience. Our experienced designers specialize in creating engaging layouts, incorporating compelling graphics, and ensuring a cohesive visual narrative that complements content on any subject.

#ezw_tco-2 .ez-toc-widget-container ul.ez-toc-list li.active::before { background-color: #ededed; } Table of contents

- Presenting techniques

- 50 tips on how to improve PowerPoint presentations in 2022-2023 [Updated]

- Present financial information visually in PowerPoint to drive results

- Keynote VS PowerPoint

- Design Tips

8 rules of effective presentation

- Business Slides

Employee training and onboarding presentation: why and how

How to structure, design, write, and finally present executive summary presentation?

How to Give a Good Academic Paper Presentation

- Post author By Maria Angel Ferrero

- Post date August 17, 2020

- No Comments on How to Give a Good Academic Paper Presentation

The art of pitching your academic research

So, you’re about to present your first academic paper? You are preparing to defend your thesis? You are about to present your research to a bunch of experts?

But, you don’t know where to start? or, how to start?

That’s ok, you are in the right place.

In this short post, I’m going to show you how to do a good academic research presentation so that your audience actually understands and appreciates it.

The main goal of an academic research presentation — like any other type of presentation — is to carry your audience through a story and grab their attention during the whole story. But no matter how good a story is, if it’s not told properly it’ll lose its audience at the very first words.

And every good story needs a good structure, otherwise, your audience will get lost in a dead-end.

To avoid getting into that dead-end and losing your audience, you should structure your presentation around 5 main questions:

- Who are you and what’s your story about?

- Why should your audience — or anyone — care about your story, and why is it relevant to tell that story now?

- How did you get to write your story? Who are the main characters?

- What happens in the story? What happens to the characters?

- So, What? Why this ending is better? Why should I wait for a new episode?

The order in which these questions are answered throughout your presentation can vary. Good stories might also start at the end and crawl back to its beginnings. Play with the order and see what suits best your story, only you know better what works for your research.

So let’s go now through each of the questions, shall we?

Who are you and what’s your research about?

Introduce yourself — unless you have already been introduced. Sometimes we are so impatience to give our presentation that we forget the basics.

Many times when we choose a book to read we ask ourselves about the human that wrote the book. And, as any writer researchers should include a short biography of themselves in the presentation.

And this is not to brag about yourself or your experience, but to give a human touch to the research itself. Before anyone wants to hear your story — your research — you need to tell them why they should be listening to you.

A short introduction of 30 seconds will do, your name, your background, why you are here in this room presenting and anything else that might be relevant to the research you are doing.

Give a context to your story, a kind of foreword to your research. State your thesis clearly and tell your audience why the topic you are going to address is relevant. And why they should care.

Give a hook. Start with a kind of provocation to instill curiosity and need. Try to think out of the box and talk about something your audience will found interesting. Use analogies too much known or simpler things that everyone in the room would be able to understand. Don’t talk to the experts, they already know it.

To give you an example, this is how I started one of my papers on overconfidence and innovation:

If you had to choose between The Joker and Batman, who would you want to be?

My paper was nothing to do with superheroes — at least not in a common way — but I wanted to talk about the dual personality innovators have, thus The Joker vs Batman analogy.

Once you have given your hook and presented yourself, give your audience an idea of what you are going to talk about and what awaits them during the following minutes.

Give them a roadmap of the talk, even if it seems redundant to you. This doesn’t mean you have to list your table of contents, just a prelude of your story.

In total, one minute and one slide are enough.

Why should your audience care about your Research, and why is it relevant now?

The next 2 or 3 slides should introduce the subject to the audience. Very briefly. Usually, research presentations last between 10 to 15 minutes, but many are shifting to the startup pitch format of 3 to 5 minutes. So being concise and direct to point is quite important.

Telling your audience why the topic you are researching about is important and relevant it’s essential, but should not take all time. This is just the introduction, you need to save time for the main story.

There are mainly 6 elements that make a good introduction:

- Define the Problem: Many speakers forget this simple point. No matter how difficult and technical the problem you are addressing is there is certainly a way to explain it concisely and clearly in less than one minute. Explain your problem as if your audience were 5 years old children, not because they are not smart or respectable, but because the simpler you get to explain a complex problem the more it shows your mastery and preparation. If the audience doesn’t understand the problem being attacked, then they won’t understand the rest of your talk, and you’ll lose them before you get to your great solution. For your slides, condense the problem into a very few carefully chosen words. An example here again from my research: Is being extremely confident in ourselves good or bad for innovation?

- Motivate the Audience: Explain why the problem is so important. How does the problem fit into the larger picture(e.g. entrepreneurship ecosystem, neuroscience,…)? What are its applications? What makes the problem nontrivial? If no one has done this research, why is it relevant now to do it? What are the circumstances that make it relevant now more than ever? Avoid broad statements such as “Innovation is what drives economic growth, but there are few innovative individuals, so how can we encourage people to become innovators?” Rather, focus on what really matters: “ universities are investing millions to develop entrepreneurship education program, still students graduating from these programs aren’t starting any venture.”

- Introduce Terminology: scientific jargon is boring and complex, it should be kept to a minimum. However, sometimes is almost impossible not to refer to specific scientific terms. Any complex jargon should be introduced at the beginning of the presentation or when each term is introduced for the first time during the presentation. To avoid losing time tot his, you can prepare a short document with all the terms and definitions to hand out to the participants in the audience.

- Discuss Earlier Work: Do your research, you are not reinventing the wheel. There is nothing more frustrating than listening to a talk that covers something that has already been published without making reference tot hose studies. It not only shows that you didn’t do your research and that you are underprepared, but it shows you don’t know how to conduct research. This doesn’t mean that you should have read and cited ALL the works and papers that talk about the topic of your research. This is only useful if you are doing a systematic review. But you have to be sure that you know, read and cite those that really matter. You have to explain why this work is different from past wor, or how you are improving or continuing the research.

- Emphasize the Contributions of the Paper: Make sure that you explicitly and succinctly state the contributions made by your paper. That is the so what?. Give just a quick glimpse of your contributions and implications for the research and the practice. The audience wants to know this. Often it is the only thing that they carry away from the talk.

- Consider putting your Conclusion in the Introduction : Be bold. Let everyone know from the start where you are headed so that the audience can focus on what matters.

How did you get to your results? How did you conduct your study?

There should be 1 or 2 methods slides that allow the audience to understand how the research was conducted. You might include a flow chart describing the main ingredients of the methods used. Do not put too many details, just what it’s needed to understand the study. Many of the details are appropriate for the manuscript but not for the presentation. If the audience wants to have more details on the methods they can always read your full paper, or you can prepare backup slides with this information to share during the Q&As session. For example, you could just say: “During 4 weeks we conducted semi-structured interviews with top managers and employees from different organizations. Our final sample was composed of 30 individuals, from which 10 were top managers and 15 were female and aged between 25 and 60 years.” Further details are presented in backup slides or in the manuscript.

What did you find, what happened?

The next 3 slides should show the main results obtained with your research. If appropriate, it is nice to start with a slide showing the basic phenomena being studied (e.G. the process of innovation and how). It reminds your audience about the variables used and manipulated and the role they have in the situation being studied.

Next, show figures, pictures, or graphs that clearly illustrate the main results. Do not show charts and tables of raw data. No one is able to read an excel table on a presentation, if only it gives the creeps. So instead of putting large and ugly tables, no one is going to read, use beautiful and meaningful graphs and figures.

You can use free infographic apps to build awesome visual representations of your data. Apps like Canva , Venngage , or Piktochart work great.

All figures should be clearly labeled. When showing figures, be sure to explain the figure axes before you talk about the data (e.g., “the X-axis shows time. The Y-axis shows economic profit).

When presenting the data try to be as simple as possible, this is the most complex part of your research. You might be an expert, but your audience probably is not and they need to understand your results if you want to convenience them with your research.

So, What? What are the outcomes, implications and future steps?

The last 2 slides are probably the most important section of your presentation. It’s the denouement of your story, and it should be good.

Nothing is more frustrating than reading or listening to a good story to arrive to a disappointing end. All the effort you did to tell the good story is lost if you don’t curate appropriately the ending.

Some people be distracted during the whole presentation and would only pay attention to your conclusions, so those conclusions better are good.

Before getting to your end, sum up what your study was about, your research questions and objectives, and then go to the conclusion. In this way, the lousy distracted audience will also get most of your research.

List the conclusions in clear, easy to understand language. You can read them to the audience. Also give one or two sentences about what this likely means — your interpretation — for the big picture, go back to the context and motives of your research. Explain how your results improve our understanding and contribute to theory and practice.

Don’t be afraid to talk about the flaws and limitations of your study. Not only this shows you are humble but that you are prepared enough and that you are aware that things can be improved. Remember that having contradictory results to what you expected is not a bad thing, they are still results, you need to find an explanation to this.

Once you know your limitations, tell your audience how can this be improved in future research. How can other scholars address the problems and flaws, what are the next steps, and what future research should focus on?

Your job as a presenter is to not only present the paper but also lead a discussion with your audience about your research. Talk about its strengths, weaknesses, and broader implications. To help focus the class discussion, end your presentation with a list of approximately three major questions/issues worthy of further discussion.

Please finalize your presentation with at least two or three major things that should be discussed. Discussion with the audience should be especially encouraged at this point, but you should be prepared to foster this by raising these issues.

So, when preparing your presentation think like one of the people in your audience. Think about what they would ask? What would they like to discuss further? What are the points that might trigger confusion or disagreement?

If you have these questions in mind you can prepare to give appropriate answers and be less stressed out by the uncertainty of your audience reaction. You can then prepare a couple of backup slides that will help you give responses to the questions being asked and that will help you make your point.

Final thoughts

Reading and understanding academic research papers can be a tough assignment, especially because it can be very specific and you might not know or understand many terms, methodologies, or even statistical models and analysis. So preparing a presentation of an academic paper, whether is yours or others’ work, takes time and must be taken seriously.

When you are preparing your draft for the presentation, keep in mind that your audience will rely on listening comprehension, not reading comprehension. That means that your ideas need to be clear and to the point, and organized in a way that makes it possible for your audience to follow you.

And since understanding was difficult for you who had the time to read and discuss the paper with your team, you can imagine how difficult it might be for an audience that hasn’t read the paper and moreover has no expertise (or not much) on the research topic you are presenting.

So you have to be very careful about how you present your article so that your audience understands what you are saying, feel involved and curious, and off course don’t sleep while you talk.

Scientific oral presentations are not simply readings of scientific manuscripts, so being in front of an audience reading scientific terms and statistical models and equations is out of the picture. You need to provoke curiosity and engagement so that at the end of your presentation people want to know more about your research.

Don’t forget that time is precious, and not everyone is ready to give their time to listen to things they don’t find amusing or intriguing. Being concise and simple is not an easy exercise, but is crucial for passing by a message.

Follow simple presentation rules:

- 1 slide takes 1 minute to present, so if you have 10 minutes to present don’t do more than 10 slides.

- Don’t use small size fonts, the minimum readable size is 20pt.

- Don’t use text when you don’t need it, the text should be only be used to highlight things that you want your audience to remember

- Use pictures whenever you can but don’t overuse them. Pictures have to be relevant to your speech.

- Be careful with grammar and errors. Read your slides thoroughly a couple of times before submitting them for a presentation. And ask someone else to read them also, they are more likely to find mistakes than you are as they are less biased and less attached to your topic.

- Finally, prepare, prepare, and prepare. Mastery is only possible through training. No matter how good you are at improvising, preparing for a presentation is key for succeeding at it.

And that’s it. Good luck!

- Tags Research , Research Paper , Science , Scientific Paper

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

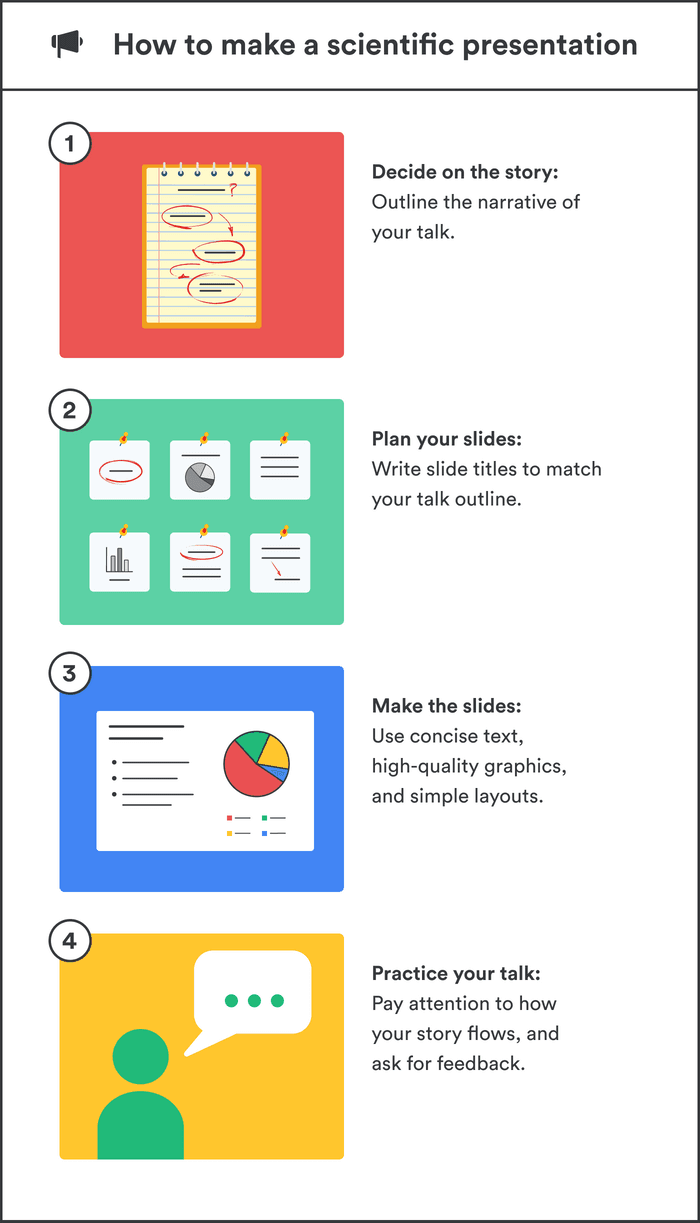

How to make a scientific presentation

Scientific presentation outlines

Questions to ask yourself before you write your talk, 1. how much time do you have, 2. who will you speak to, 3. what do you want the audience to learn from your talk, step 1: outline your presentation, step 2: plan your presentation slides, step 3: make the presentation slides, slide design, text elements, animations and transitions, step 4: practice your presentation, final thoughts, frequently asked questions about preparing scientific presentations, related articles.

A good scientific presentation achieves three things: you communicate the science clearly, your research leaves a lasting impression on your audience, and you enhance your reputation as a scientist.

But, what is the best way to prepare for a scientific presentation? How do you start writing a talk? What details do you include, and what do you leave out?

It’s tempting to launch into making lots of slides. But, starting with the slides can mean you neglect the narrative of your presentation, resulting in an overly detailed, boring talk.

The key to making an engaging scientific presentation is to prepare the narrative of your talk before beginning to construct your presentation slides. Planning your talk will ensure that you tell a clear, compelling scientific story that will engage the audience.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to make a good oral scientific presentation, including:

- The different types of oral scientific presentations and how they are delivered;

- How to outline a scientific presentation;

- How to make slides for a scientific presentation.

Our advice results from delving into the literature on writing scientific talks and from our own experiences as scientists in giving and listening to presentations. We provide tips and best practices for giving scientific talks in a separate post.

There are two main types of scientific talks:

- Your talk focuses on a single study . Typically, you tell the story of a single scientific paper. This format is common for short talks at contributed sessions in conferences.

- Your talk describes multiple studies. You tell the story of multiple scientific papers. It is crucial to have a theme that unites the studies, for example, an overarching question or problem statement, with each study representing specific but different variations of the same theme. Typically, PhD defenses, invited seminars, lectures, or talks for a prospective employer (i.e., “job talks”) fall into this category.

➡️ Learn how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

The length of time you are allotted for your talk will determine whether you will discuss a single study or multiple studies, and which details to include in your story.

The background and interests of your audience will determine the narrative direction of your talk, and what devices you will use to get their attention. Will you be speaking to people specializing in your field, or will the audience also contain people from disciplines other than your own? To reach non-specialists, you will need to discuss the broader implications of your study outside your field.

The needs of the audience will also determine what technical details you will include, and the language you will use. For example, an undergraduate audience will have different needs than an audience of seasoned academics. Students will require a more comprehensive overview of background information and explanations of jargon but will need less technical methodological details.

Your goal is to speak to the majority. But, make your talk accessible to the least knowledgeable person in the room.

This is called the thesis statement, or simply the “take-home message”. Having listened to your talk, what message do you want the audience to take away from your presentation? Describe the main idea in one or two sentences. You want this theme to be present throughout your presentation. Again, the thesis statement will depend on the audience and the type of talk you are giving.

Your thesis statement will drive the narrative for your talk. By deciding the take-home message you want to convince the audience of as a result of listening to your talk, you decide how the story of your talk will flow and how you will navigate its twists and turns. The thesis statement tells you the results you need to show, which subsequently tells you the methods or studies you need to describe, which decides the angle you take in your introduction.

➡️ Learn how to write a thesis statement

The goal of your talk is that the audience leaves afterward with a clear understanding of the key take-away message of your research. To achieve that goal, you need to tell a coherent, logical story that conveys your thesis statement throughout the presentation. You can tell your story through careful preparation of your talk.

Preparation of a scientific presentation involves three separate stages: outlining the scientific narrative, preparing slides, and practicing your delivery. Making the slides of your talk without first planning what you are going to say is inefficient.

Here, we provide a 4 step guide to writing your scientific presentation:

- Outline your presentation

- Plan your presentation slides

- Make the presentation slides

- Practice your presentation

Writing an outline helps you consider the key pieces of your talk and how they fit together from the beginning, preventing you from forgetting any important details. It also means you avoid changing the order of your slides multiple times, saving you time.

Plan your talk as discrete sections. In the table below, we describe the sections for a single study talk vs. a talk discussing multiple studies:

The following tips apply when writing the outline of a single study talk. You can easily adapt this framework if you are writing a talk discussing multiple studies.

Introduction: Writing the introduction can be the hardest part of writing a talk. And when giving it, it’s the point where you might be at your most nervous. But preparing a good, concise introduction will settle your nerves.

The introduction tells the audience the story of why you studied your topic. A good introduction succinctly achieves four things, in the following order.

- It gives a broad perspective on the problem or topic for people in the audience who may be outside your discipline (i.e., it explains the big-picture problem motivating your study).

- It describes why you did the study, and why the audience should care.

- It gives a brief indication of how your study addressed the problem and provides the necessary background information that the audience needs to understand your work.

- It indicates what the audience will learn from the talk, and prepares them for what will come next.

A good introduction not only gives the big picture and motivations behind your study but also concisely sets the stage for what the audience will learn from the talk (e.g., the questions your work answers, and/or the hypotheses that your work tests). The end of the introduction will lead to a natural transition to the methods.

Give a broad perspective on the problem. The easiest way to start with the big picture is to think of a hook for the first slide of your presentation. A hook is an opening that gets the audience’s attention and gets them interested in your story. In science, this might take the form of a why, or a how question, or it could be a statement about a major problem or open question in your field. Other examples of hooks include quotes, short anecdotes, or interesting statistics.

Why should the audience care? Next, decide on the angle you are going to take on your hook that links to the thesis of your talk. In other words, you need to set the context, i.e., explain why the audience should care. For example, you may introduce an observation from nature, a pattern in experimental data, or a theory that you want to test. The audience must understand your motivations for the study.

Supplementary details. Once you have established the hook and angle, you need to include supplementary details to support them. For example, you might state your hypothesis. Then go into previous work and the current state of knowledge. Include citations of these studies. If you need to introduce some technical methodological details, theory, or jargon, do it here.

Conclude your introduction. The motivation for the work and background information should set the stage for the conclusion of the introduction, where you describe the goals of your study, and any hypotheses or predictions. Let the audience know what they are going to learn.

Methods: The audience will use your description of the methods to assess the approach you took in your study and to decide whether your findings are credible. Tell the story of your methods in chronological order. Use visuals to describe your methods as much as possible. If you have equations, make sure to take the time to explain them. Decide what methods to include and how you will show them. You need enough detail so that your audience will understand what you did and therefore can evaluate your approach, but avoid including superfluous details that do not support your main idea. You want to avoid the common mistake of including too much data, as the audience can read the paper(s) later.

Results: This is the evidence you present for your thesis. The audience will use the results to evaluate the support for your main idea. Choose the most important and interesting results—those that support your thesis. You don’t need to present all the results from your study (indeed, you most likely won’t have time to present them all). Break down complex results into digestible pieces, e.g., comparisons over multiple slides (more tips in the next section).

Summary: Summarize your main findings. Displaying your main findings through visuals can be effective. Emphasize the new contributions to scientific knowledge that your work makes.

Conclusion: Complete the circle by relating your conclusions to the big picture topic in your introduction—and your hook, if possible. It’s important to describe any alternative explanations for your findings. You might also speculate on future directions arising from your research. The slides that comprise your conclusion do not need to state “conclusion”. Rather, the concluding slide title should be a declarative sentence linking back to the big picture problem and your main idea.

It’s important to end well by planning a strong closure to your talk, after which you will thank the audience. Your closing statement should relate to your thesis, perhaps by stating it differently or memorably. Avoid ending awkwardly by memorizing your closing sentence.

By now, you have an outline of the story of your talk, which you can use to plan your slides. Your slides should complement and enhance what you will say. Use the following steps to prepare your slides.

- Write the slide titles to match your talk outline. These should be clear and informative declarative sentences that succinctly give the main idea of the slide (e.g., don’t use “Methods” as a slide title). Have one major idea per slide. In a YouTube talk on designing effective slides , researcher Michael Alley shows examples of instructive slide titles.

- Decide how you will convey the main idea of the slide (e.g., what figures, photographs, equations, statistics, references, or other elements you will need). The body of the slide should support the slide’s main idea.

- Under each slide title, outline what you want to say, in bullet points.

In sum, for each slide, prepare a title that summarizes its major idea, a list of visual elements, and a summary of the points you will make. Ensure each slide connects to your thesis. If it doesn’t, then you don’t need the slide.

Slides for scientific presentations have three major components: text (including labels and legends), graphics, and equations. Here, we give tips on how to present each of these components.

- Have an informative title slide. Include the names of all coauthors and their affiliations. Include an attractive image relating to your study.

- Make the foreground content of your slides “pop” by using an appropriate background. Slides that have white backgrounds with black text work well for small rooms, whereas slides with black backgrounds and white text are suitable for large rooms.

- The layout of your slides should be simple. Pay attention to how and where you lay the visual and text elements on each slide. It’s tempting to cram information, but you need lots of empty space. Retain space at the sides and bottom of your slides.

- Use sans serif fonts with a font size of at least 20 for text, and up to 40 for slide titles. Citations can be in 14 font and should be included at the bottom of the slide.

- Use bold or italics to emphasize words, not underlines or caps. Keep these effects to a minimum.

- Use concise text . You don’t need full sentences. Convey the essence of your message in as few words as possible. Write down what you’d like to say, and then shorten it for the slide. Remove unnecessary filler words.

- Text blocks should be limited to two lines. This will prevent you from crowding too much information on the slide.

- Include names of technical terms in your talk slides, especially if they are not familiar to everyone in the audience.

- Proofread your slides. Typos and grammatical errors are distracting for your audience.

- Include citations for the hypotheses or observations of other scientists.

- Good figures and graphics are essential to sustain audience interest. Use graphics and photographs to show the experiment or study system in action and to explain abstract concepts.

- Don’t use figures straight from your paper as they may be too detailed for your talk, and details like axes may be too small. Make new versions if necessary. Make them large enough to be visible from the back of the room.

- Use graphs to show your results, not tables. Tables are difficult for your audience to digest! If you must present a table, keep it simple.

- Label the axes of graphs and indicate the units. Label important components of graphics and photographs and include captions. Include sources for graphics that are not your own.

- Explain all the elements of a graph. This includes the axes, what the colors and markers mean, and patterns in the data.

- Use colors in figures and text in a meaningful, not random, way. For example, contrasting colors can be effective for pointing out comparisons and/or differences. Don’t use neon colors or pastels.

- Use thick lines in figures, and use color to create contrasts in the figures you present. Don’t use red/green or red/blue combinations, as color-blind audience members can’t distinguish between them.

- Arrows or circles can be effective for drawing attention to key details in graphs and equations. Add some text annotations along with them.

- Write your summary and conclusion slides using graphics, rather than showing a slide with a list of bullet points. Showing some of your results again can be helpful to remind the audience of your message.

- If your talk has equations, take time to explain them. Include text boxes to explain variables and mathematical terms, and put them under each term in the equation.

- Combine equations with a graphic that shows the scientific principle, or include a diagram of the mathematical model.

- Use animations judiciously. They are helpful to reveal complex ideas gradually, for example, if you need to make a comparison or contrast or to build a complicated argument or figure. For lists, reveal one bullet point at a time. New ideas appearing sequentially will help your audience follow your logic.

- Slide transitions should be simple. Silly ones distract from your message.

- Decide how you will make the transition as you move from one section of your talk to the next. For example, if you spend time talking through details, provide a summary afterward, especially in a long talk. Another common tactic is to have a “home slide” that you return to multiple times during the talk that reinforces your main idea or message. In her YouTube talk on designing effective scientific presentations , Stanford biologist Susan McConnell suggests using the approach of home slides to build a cohesive narrative.

To deliver a polished presentation, it is essential to practice it. Here are some tips.

- For your first run-through, practice alone. Pay attention to your narrative. Does your story flow naturally? Do you know how you will start and end? Are there any awkward transitions? Do animations help you tell your story? Do your slides help to convey what you are saying or are they missing components?

- Next, practice in front of your advisor, and/or your peers (e.g., your lab group). Ask someone to time your talk. Take note of their feedback and the questions that they ask you (you might be asked similar questions during your real talk).

- Edit your talk, taking into account the feedback you’ve received. Eliminate superfluous slides that don’t contribute to your takeaway message.

- Practice as many times as needed to memorize the order of your slides and the key transition points of your talk. However, don’t try to learn your talk word for word. Instead, memorize opening and closing statements, and sentences at key junctures in the presentation. Your presentation should resemble a serious but spontaneous conversation with the audience.

- Practicing multiple times also helps you hone the delivery of your talk. While rehearsing, pay attention to your vocal intonations and speed. Make sure to take pauses while you speak, and make eye contact with your imaginary audience.

- Make sure your talk finishes within the allotted time, and remember to leave time for questions. Conferences are particularly strict on run time.

- Anticipate questions and challenges from the audience, and clarify ambiguities within your slides and/or speech in response.

- If you anticipate that you could be asked questions about details but you don’t have time to include them, or they detract from the main message of your talk, you can prepare slides that address these questions and place them after the final slide of your talk.

➡️ More tips for giving scientific presentations

An organized presentation with a clear narrative will help you communicate your ideas effectively, which is essential for engaging your audience and conveying the importance of your work. Taking time to plan and outline your scientific presentation before writing the slides will help you manage your nerves and feel more confident during the presentation, which will improve your overall performance.

A good scientific presentation has an engaging scientific narrative with a memorable take-home message. It has clear, informative slides that enhance what the speaker says. You need to practice your talk many times to ensure you deliver a polished presentation.

First, consider who will attend your presentation, and what you want the audience to learn about your research. Tailor your content to their level of knowledge and interests. Second, create an outline for your presentation, including the key points you want to make and the evidence you will use to support those points. Finally, practice your presentation several times to ensure that it flows smoothly and that you are comfortable with the material.

Prepare an opening that immediately gets the audience’s attention. A common device is a why or a how question, or a statement of a major open problem in your field, but you could also start with a quote, interesting statistic, or case study from your field.

Scientific presentations typically either focus on a single study (e.g., a 15-minute conference presentation) or tell the story of multiple studies (e.g., a PhD defense or 50-minute conference keynote talk). For a single study talk, the structure follows the scientific paper format: Introduction, Methods, Results, Summary, and Conclusion, whereas the format of a talk discussing multiple studies is more complex, but a theme unifies the studies.

Ensure you have one major idea per slide, and convey that idea clearly (through images, equations, statistics, citations, video, etc.). The slide should include a title that summarizes the major point of the slide, should not contain too much text or too many graphics, and color should be used meaningfully.

IMAGES

VIDEO