🚀 Work With Us

Private Coaching

Language Editing

Qualitative Coding

✨ Free Resources

Templates & Tools

Short Courses

Articles & Videos

How To Write A Literature Review

A Plain-Language Tutorial (With Examples) + Free Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Q uality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

⚡ GET THE FREE TEMPLATE ⚡

Fast-track your research with our award-winning Lit Review Template .

Download Now 📂

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

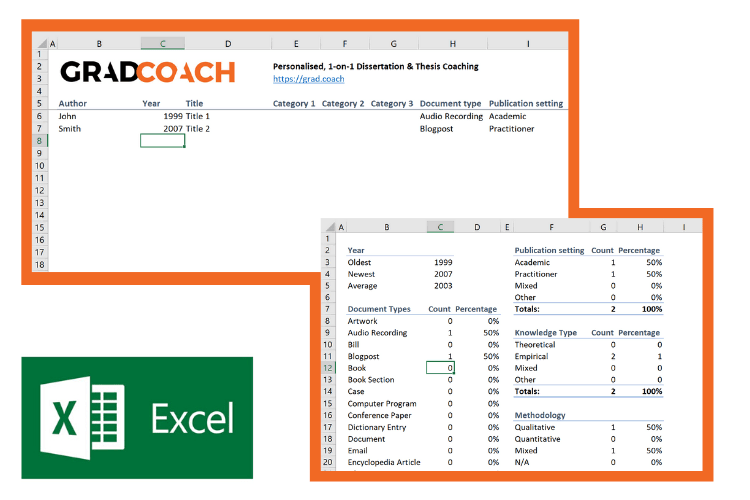

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

⚡ THE #1 LITERATURE REVIEW CHECKLIST ⚡

Give your markers EXACTLY what they want with our FREE checklist.

Download For Free 📄

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Learn More About The Lit Review:

How To Choose A Tutor For Your Dissertation

Hiring the right tutor for your dissertation or thesis can make the difference between passing and failing. Here’s what you need to consider.

5 Signs You Need A Dissertation Helper

Discover the 5 signs that suggest you need a dissertation helper to get unstuck, finish your degree and get your life back.

Writing A Literature Review: 4 Time-Saving Hacks

🎙️ PODCAST: Ace The Literature Review 4 Time-Saving Tips To Fast-Track Your Literature...

Research Question 101: Everything You Need To Know

Learn what a research question is, how it’s different from a research aim or objective, and how to write a high-quality research question.

Research Question Examples: The Perfect Starting Point

See what quality research questions look like across multiple topic areas, including psychology, business, computer science and more.

📄 FREE TEMPLATES

Research Topic Ideation

Proposal Writing

Literature Review

Methodology & Analysis

Academic Writing

Referencing & Citing

Apps, Tools & Tricks

The Grad Coach Podcast

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.

I learn a lot from your videos. Very comprehensive and detailed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. As a research student, you learn better with your learning tips in research

I was really stuck in reading and gathering information but after watching these things are cleared thanks, it is so helpful.

Really helpful, Thank you for the effort in showing such information

This is super helpful thank you very much.

Thank you for this whole literature writing review.You have simplified the process.

I’m so glad I found GradCoach. Excellent information, Clear explanation, and Easy to follow, Many thanks Derek!

You’re welcome, Maithe. Good luck writing your literature review 🙂

Thank you Coach, you have greatly enriched and improved my knowledge

Great piece, so enriching and it is going to help me a great lot in my project and thesis, thanks so much

This is THE BEST site for ANYONE doing a masters or doctorate! Thank you for the sound advice and templates. You rock!

Thanks, Stephanie 🙂

This is mind blowing, the detailed explanation and simplicity is perfect.

I am doing two papers on my final year thesis, and I must stay I feel very confident to face both headlong after reading this article.

thank you so much.

if anyone is to get a paper done on time and in the best way possible, GRADCOACH is certainly the go to area!

This is very good video which is well explained with detailed explanation

Thank you excellent piece of work and great mentoring

Thanks, it was useful

Thank you very much. the video and the information were very helpful.

Good morning scholar. I’m delighted coming to know you even before the commencement of my dissertation which hopefully is expected in not more than six months from now. I would love to engage my study under your guidance from the beginning to the end. I love to know how to do good job

Thank you so much Derek for such useful information on writing up a good literature review. I am at a stage where I need to start writing my one. My proposal was accepted late last year but I honestly did not know where to start

Like the name of your YouTube implies you are GRAD (great,resource person, about dissertation). In short you are smart enough in coaching research work.

This is a very well thought out webpage. Very informative and a great read.

Very timely.

I appreciate.

Very comprehensive and eye opener for me as beginner in postgraduate study. Well explained and easy to understand. Appreciate and good reference in guiding me in my research journey. Thank you

Thank you. I requested to download the free literature review template, however, your website wouldn’t allow me to complete the request or complete a download. May I request that you email me the free template? Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

- Print Friendly

Writing the Dissertation - Guides for Success: Literature Review

- Writing the Dissertation Homepage

- Overview and Planning

- Research Question

- Literature Review

- Methodology

- Results and Discussion

- Getting Started

- Research Gap

- What to Avoid

Overview of writing the literature review

Conducting a literature review enables you to demonstrate your understanding and knowledge of the existing work within your field of research. Doing so allows you to identify any underdeveloped areas or unexplored issues within a specific debate, dialogue or field of study. This, in turn, helps you to clearly and persuasively demonstrate how your own research will address one or more of these gaps.

Disciplinary differences

Please note: this guide is not specific to any one discipline. The literature review can vary depending on the nature of the research and the expectations of the school or department. Please adapt the following advice to meet the demands of your dissertation and the expectations of your school or department. Consult your supervisor for further guidance; you can also check out Writing Across Subjects guide .

Guide contents

As part of the Writing the Dissertation series, this guide covers the most common expectations for the literature review chapter, giving you the necessary knowledge, tips and guidance needed to impress your markers! The sections are organised as follows:

- Getting Started - Defines the literature review and presents a table to help you plan.

- Process - Explores choosing a topic, searching for sources and evaluating what you find.

- Structure - Presents key principles to consider in terms of structure, with examples to illustrate the concepts.

- Research gap - Clarifies what is meant by 'gap' and gives examples of common types of gaps.

- What to Avoid - Covers a few frequent mistakes you'll want to...avoid!

- FAQs - Answers to common questions about research gaps, literature availability and more.

- Checklist - Includes a summary of key points and a self-evaluation checklist.

Training and tools

- The Academic Skills team has recorded a Writing the Dissertation workshop series to help you with each section of a standard dissertation, including a video on writing the literature review .

- Check out the library's online Literature Review: Research Methods training.

- Our literature reviews summary guide provides links to further information and videos.

- The dissertation planner tool can help you think through the timeline for planning, research, drafting and editing.

- iSolutions offers training and a Word template to help you digitally format and structure your dissertation.

What is the literature review?

The literature review of a dissertation gives a clear, critical overview of a specific area of research. Our main Writing the Dissertation - Overview and Planning guide explains how you can refine your dissertation topic and begin your initial research; the next tab of this guide, 'Process', expands on those ideas. In summary, the process of conducting a literature review usually involves the following:

- Conducting a series of strategic searches to identify the key texts within that topic.

- Identifying the main argument in each source, the relevant themes and issues presented and how they relate to each other.

- Critically evaluating your chosen sources and determining their strengths, weaknesses, relevance and value to your research along with their overall contribution to the broader research field.

- Identifying any gaps or flaws in the literature which your research can address.

Literature review as both process and product

Writers should keep in mind that the phrase 'literature review' refers to two related, but distinct, things:

- 'Literature review' refers, first, to the active process of discovering and assessing relevant literature.

- 'Literature review' refers, second, to the written product that emerges from the above process.

This distinction is vital to note because every dissertation requires the writer to engage with and consider existing literature (i.e., to undertake the active process ). Research doesn't exist in a void, and it's crucial to consider how our work builds from or develops existing foundations of thought or discovery. Thus, even if your discipline doesn't require you to include a chapter titled 'Literature Review' in your submitted dissertation, you should expect to engage with the process of reviewing literature.

Why is it important to be aware of existing literature?

- You are expected to explain how your research fits in with other research in your field and, perhaps, within the wider academic community.

- You will be expected to contribute something new, or slightly different, so you need to know what has already been done.

- Assessing the existing literature on your topic helps you to identify any gaps or flaws within the research field. This, in turn, helps to stimulate new ideas, such as addressing any gaps in knowledge, or reinforcing an existing theory or argument through new and focused research.

Not all literature reviews are the same. For example, in many subject areas, you are expected to include the literature review as its own chapter in your dissertation. However, in other subjects, the dissertation structure doesn't include a dedicated literature review chapter; any literature the writer has reviewed is instead incorporated in other relevant sections such as the introduction, methodology or discussion.

For this reason, there are a number of questions you should discuss with your supervisor before starting your literature review. These questions are also great to discuss with peers in your degree programme. These are outlined in the table below (see the Word document for a copy you can save and edit):

- Dissertation literature review planning table

Literature review: the process

Conducting a literature review requires you to stay organised and bring a systematic approach to your thinking and reading. Scroll to continue reading, or click a link below to jump immediately to that section:

Choosing a topic

The first step of any research project is to select an interesting topic. From here, the research phase for your literature review helps to narrow down your focus to a particular strand of research and to a specific research question . This process of narrowing and refining your research topic is particularly important because it helps you to maintain your focus and manage your material without becoming overwhelmed by sources and ideas.

Try to choose something that hasn’t been researched to death. This way, you stand a better chance of making a novel contribution to the research field.

Conversely, you should avoid undertaking an area of research where little to no work has been done. There are two reasons for this:

- Firstly, there may be a good reason for the lack of research on a topic (e.g. is the research useful or worthwhile pursuing?).

- Secondly, some research projects, particularly practice-based ones involving primary research, can be too ambitious in terms of their scope and the availability of resources. Aim to contribute to a topic, not invent one!

Searching for sources

Researching and writing a literature review is partly about demonstrating your independent research skills. Your supervisor may have some tips relating to your discipline and research topic, but you should be proactive in finding a range of relevant sources. There are various ways of tracking down the literature relevant to your project, as outlined below.

Make use of Library Search

One thing you don’t want to do is simply type your topic into Google and see what comes up. Instead, use Library Search to search the Library’s catalogue of books, media and articles.

Online training for 'Using databases' and 'Finding information' can be found here . You can also use the Library's subject pages to discover databases and resources specific to your academic discipline.

Engage with others working in your area

As well as making use of library resources, it can be helpful to discuss your work with students or academics working in similar areas. Think about attending relevant conferences and/or workshops which can help to stimulate ideas and allows you to keep track of the most current trends in your research field.

Look at the literature your sources reference

Finding relevant literature can, at times, be a long and slightly frustrating experience. However, one good source can often make all the difference. When you find a good source that is both relevant and valuable to your research, look at the material it cites throughout and follow up any sources that are useful. Also check if your source has been cited in any more recent publications.

Think of the bibliography/references page of a good source as a series of breadcrumbs that you can follow to find even more great material.

Evaluating sources

It is very important to be selective when choosing the final sources to include in your literature review. Below are some of the key questions to ask yourself:

- If a source is tangentially interesting but hasn’t made any particular contribution to your topic, it probably shouldn’t be included in your literature review. You need to be able to demonstrate how it fits in with the other sources under consideration, and how it has helped shape the current state of the literature.

- There might be a wealth of material available on your chosen subject, but you need to make sure that the sources you use are appropriate for your assignment. The safest approach to take is to use only academic work from respected publishers. However, on occasions, you might need to deviate from traditional academic literature in order to find the information you need. In many cases, the problem is not so much the sources you use, but how you use them. Where relevant, information from newspapers, websites and even blogs are often acceptable, but you should be careful how you use that information. Do not necessarily take any information as factual. Instead be critical and interpret the material in the context of your research. Consider who the writer is and how this might influence the authority and reliability of the information presented. Consult your supervisor for more specific guidance relating to your research.

- The mere fact that something has been published does not automatically guarantee its quality, even if it comes from a reputable publisher. You will need to critique the content of the source. Has the author been thorough and consistent in their methodology? Do they present their thesis coherently? Most importantly, have they made a genuine contribution to the topic?

Keeping track of your sources

Once you have selected a source to use in your literature review, it is useful to make notes on all of its key features, including where it comes from, what it says, and what its main strengths and weaknesses are. This way you can easily re-familiarise yourself with a source without having to re-read it. Keeping an annotated bibliography or completing source evaluation tables are a couple ways to do this.

Digital notebooks such as OneNote are another great option. You can keep all your notes and evaluation in one place, organising according to either subtopics/themes or sources. Customise the sections and pages of your notebook so it is easy to navigate and feels intuitive to how you think and process information. The video below will help you get started.

Writing your literature review

As we explored in the 'Getting Started' tab, the literature review is both a process you follow and (in most cases) a written chapter you produce. Thus, having engaged the review process, you now need to do the writing itself. Please continue reading, or click a heading below to jump immediately to that section.

Guiding principles

The structure of the final piece will depend on the discipline within which you are working as well as the nature of your particular research project. However, here are a few general pieces of advice for writing a successful literature review:

- Show the connections between your sources. Remember that your review should be more than merely a list of sources with brief descriptions under each one. You are constructing a narrative. Show clearly how each text has contributed to the current state of the literature, drawing connections between them.

- Engage critically with your sources. This means not simply describing what they say. You should be evaluating their content: do they make sound arguments? Are there any flaws in the methodology? Are there any relevant themes or issues they have failed to address? You can also compare their relative strengths and weaknesses.

- Signpost throughout to ensure your reader can follow your narrative. Keep relating the discussion back to your specific research topic.

- Make a clear argument. Keep in mind that this is a chance to present your take on a topic. Your literature review showcases your own informed interpretation of a specific area of research. If you have followed the advice given in this guide you will have been careful and selective in choosing your sources. You are in control of how you present them to your reader.

There are several different ways to structure the literature review chapter of your dissertation. Two of the most common strategies are thematic structure and chronological structure (the two of which can also be combined ). However you structure the literature review, this section of the dissertation normally culminates in identifying the research gap.

Thematic structure

Variations of this structure are followed in most literature reviews. In a thematic structure , you organise the literature into groupings by theme (i.e., subtopic or focus). You then arrange the groupings in the most logical order, starting with the broadest (or most general) and moving to the narrowest (or most specific).

The funnel or inverted pyramid

To plan a thematic structure structure, it helps to imagine your themes moving down a funnel or inverted pyramid from broad to narrow. Consider the example depicted below, which responds to this research question:

What role did the iron rivets play in the sinking of the Titanic?

The topic of maritime disasters is the broadest theme, so it sits at the broad top of the funnel. The writer can establish some context about maritime disasters, generally, before narrowing to the Titanic, specifically. Next, the writer can narrow the discussion of the Titanic to the ship's structural integrity, specifically. Finally, the writer can narrow the discussion of structural integrity to the iron rivets, specifically. And voila: there's the research gap!

The broad-to-narrow structure is intuitive for readers. Thus, it is crucial to consider how your themes 'nest inside' one another, from the broad to the narrow. Picturing your themes as nesting dolls is another way to envision this literature review structure, as you can see in the image below.

As with the funnel, remember that the first layer (or in this case, doll) is largest because it represents the broadest theme. In terms of word count and depth, the tinier dolls will warrant more attention because they are most closely related to the research gap or question(s).

The multi-funnel variation

The example above demonstrates a research project for which one major heading might suffice, in terms of outlining the literature review. However, the themes you identify for your dissertation might not relate to one another in such a linear fashion. If this is the case, you can adapt the funnel approach to match the number of major subheadings you will need.

In the three slides below, for example, a structure is depicted for a project that investigates this (fictional) dissertation research question: does gender influence the efficacy of teacher-led vs. family-led learning interventions for children with ADHD? Rather than nesting all the subtopics or themes in a direct line, the themes fall into three major headings.

The first major heading explores ADHD from clinical and diagnostic perspectives, narrowing ultimately to gender:

- 1.1 ADHD intro

- 1.2 ADHD definitions

- 1.3 ADHD diagnostic criteria

- 1.4 ADHD gender differences

The second major heading explores ADHD within the classroom environment, narrowing to intervention types:

- 2.1 ADHD in educational contexts

- 2.2 Learning interventions for ADHD

- 2.2.1 Teacher-led interventions

- 2.2.2 Family-led interventions

The final major heading articulates the research gap (gender differences in efficacy of teacher-led vs. family-led interventions for ADHD) by connecting the narrowest themes of the prior two sections.

Multi-funnel literature review structure by Academic Skills Service

To create a solid thematic structure in a literature review, the key is thinking carefully and critically about your groupings of literature and how they relate to one another. In some cases, your themes will fit in a single funnel. In other cases, it will make sense to group your broad-to-narrow themes under several major headings, and then arrange those major headings in the most logical order.

Chronological structure

Some literature reviews will follow a chronological structure . As the name suggests, a review structured chronologically will arrange sources according to their publication dates, from earliest to most recent.

This approach can work well when your priority is to demonstrate how the research field has evolved over time. For example, a chronological arrangement of articles about artificial intelligence (AI) would allow the writer to highlight how breakthroughs in AI have built upon one another in sequential order.

A chronological structure can also suit literature reviews that need to capture how perceptions or understandings have developed across a period of time (including to the present day). For example, if your dissertation involves the public perception of marijuana in the UK, it could make sense to arrange that discussion chronologically to demonstrate key turning points and changes of majority thought.

The chronological structure can work well in some situations, such as those described above. That being said, a purely chronological structure should be considered with caution. Organising sources according to date alone runs the risk of creating a fragmented reading experience. It can be more difficult in a chronological structure to properly synthesize the literature. For these reasons, the chronological approach is often blended into a thematic structure, as you will read more about, below.

Combined structures

The structures of literature reviews can vary drastically, and for any given dissertation there will be many valid ways to arrange the literature.

For example, many literature reviews will combine the thematic and chronological approaches in different ways. A writer might match their major headings to themes or subtopics, but then arrange literature chronologically within the major themes identified. Another writer might base their major headings on chronology, but then assign thematic subheadings to each of those major headings.

When considering your options, try to imagine your reader or audience. What 'flow' will allow them to best follow the discussion you are crafting? When you are reading articles, what structural approaches do you appreciate in terms of ease and clarity?

Identifying the gap

The bulk of your literature review will explore relevant points of development and scholarly thought in your research field: in other words, 'Here is what has been done so far, thus here is where the conversation now stands'. In that way, you position your project within a wider academic discussion.

Having established that context, the literature review generally culminates in an articulation of what remains to be done: the research gap your project addresses. See the next tab for further explanation and examples.

Demystifying the research gap

The term research gap is intimidating for many students, who might mistakenly believe that every single element of their research needs to be brand new and fully innovative. This isn't the case!

The gap in many projects will be rather niche or specific. You might be helping to update or re-test knowledge rather than starting from scratch. Perhaps you have repeated a study but changed one variable. Maybe you are considering a much discussed research question, but with a lesser used methodological approach.

To demonstrate the wide variety of gaps a project could address, consider the examples below. The categories used and examples included are by no means comprehensive, but they should be helpful if you are struggling to articulate the gap your literature review has identified.

***P lease note that the content of the example statements has been invented for the sake of demonstration. The example statements should not be taken as expressions of factual information.

Gaps related to population or geography

Many dissertation research questions involve the study of a specific population. Those populations can be defined by nationality, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, socioeconomic class, political beliefs, religion, health status, or other factors. Other research questions target a specific geography (e.g. a country, territory, city, or similar). Perhaps your broader research question has been pursued by many prior scholars, but few (or no) scholars have studied the question in relation to your focal population or locale: if so, that's a gap.

- Example 1: As established above, the correlations between [ socioeconomic status ] and sustainable fashion purchases have been widely researched. However, few studies have investigated the potential relationship between [ sexual identity ] and attitudes toward sustainable fashion. Therefore...

- Example 2: Whilst the existing literature has established a clear link between [ political beliefs ] and perceptions of socialized healthcare, the influence of [ religious belief ] is less understood, particularly in regards to [ Religion ABC ].

- Example 3: Available evidence confirms that the widespread adoption of Technology XYZ in [ North America ] has improved manufacturing efficiency and reduced costs in the automotive sector. Using predictive AI models, the present research seeks to explore whether deployment of Technology XYZ could benefit the automotive sector of [ Europe ] in similar ways.

Gaps related to theoretical framework

The original contribution might involve examining something through a new lens. Theoretical framework refers, most simply, to the theory or theories a writer will use to make sense of and shape (i.e., frame ) their discussion. Perhaps your topic has been analysed in great detail through certain theoretical lenses, but you intend to frame your analysis using a theory that fewer scholars have applied to the topic: if so, that's a gap.

- Example 1: Existing discussions of the ongoing revolution in Country XYZ frame the unrest in terms of [ theory A ] and [ theory B ]. The present research will instead analyse the situation using [ theory C ], allowing greater insight into...

- Example 2: In the first section of this literature review, I examined the [ postmodern ], [ Marxist ], and [ pragmatist ] analyses that dominate academic discussion of The World According to Garp. By revisiting this modern classic through the lens of [ queer theory ], I intend to...

Gaps related to methodological approach

The research gap might be defined by differences of methodology (see our Writing the Methodology guide for more). Perhaps your dissertation poses a central question that other scholars have researched, but they have applied different methods to find the answer(s): if so, that's a gap.

- Example 1: Previous studies have relied largely upon the [ qualitative analysis of interview transcripts ] to measure the marketing efficacy of body-positive advertising campaigns. It is problematic that little quantitative data underpins present findings in this area. Therefore, I will address this research gap by [ using algorithm XYZ to quantify and analyse social-media interactions ] to determine whether...

- Example 2: Via [ quantitative and mixed-methods studies ], previous literature has explored how demographic differences influence the probability of a successful match on Dating App XYZ. By instead [ conducting a content analysis of pre-match text interactions ] on Dating App XYZ, I will...

Scarcity as a gap

Absolutes such as never and always rarely apply in academia, but here is an exception: in academia, a single study or analysis is never enough. Thus, the gap you address needn't be a literal void in the discussion. The gap could instead have to do with replicability or depth/scope. In these cases, you are adding value and contributing to the academic process by testing emerging knowledge or expanding underdeveloped discussions.

- Example: Initial research points to the efficacy of Learning Strategy ABC in helping children with dyslexia build their reading confidence. However, as detailed earlier in this review, only four published studies have tested the intervention, and two of those studies were conducted in a laboratory. To expand our growing understanding of how Learning Strategy ABC functions in classroom environments, I will...

Elapsed time as a gap

Academia values up-to-date knowledge and findings, so another valid type of gap relates to elapsed time. Many factors that can influence or shape research findings are ever evolving: technology, popular culture, and political climates, to name just a few. Due to such changes, it's important for scholars in most fields to continually update findings. Perhaps your dissertation adds value by contributing to this process.

For example, imagine if a scholar today were to rely on a handbook of marketing principles published in 1998. As good as that research might have been in 1998, technology (namely, the internet) has advanced drastically since then. The handbook's discussion of online marketing strategies will be laughably outdated when compared to more recent literature.

- Example: A wide array of literature has explored the ways in which perceptions of gender influence professional recruitment practices in the UK. The bulk of said literature, however, was published prior to the #MeToo movement and resultant shifts in discourse around gender, power imbalances and professional advancement. Therefore...

What to avoid

This portion of the guide will cover some common missteps you should try to avoid in writing your literature review. Scroll to continue reading, or click a heading below to jump immediately to that section.

Writing up before you have read up

Trying to write your literature review before you have conducted adequate research is a recipe for panic and frustration. The literature review, more than any other chapter in your dissertation, depends upon your critical understanding of a range of relevant literature. If you have only dipped your toe into the pool of literature (rather than diving in!), you will naturally struggle to develop this section of the writing. Focus on developing your relevant bases of knowledge before you commit too much time to drafting.

Believing you need to read everything

As established above, a literature review does require a significant amount of reading. However, you aren't expected to review everything ever written about your topic. Instead, aim to develop a more strategic approach to your research. A strategic approach to research looks different from one project to the next, but here are some questions to help you prioritise:

- If your field values up-to-date research and discoveries, carefully consider the 'how' and 'what' before investing time reading older sources: how will the source function in your dissertation, and what will it add to your writing?

- Try to break your research question(s) down into component parts. Then, map out where your literature review will need to provide extensive detail and where it can instead present quicker background. Allocate your research time and effort accordingly.

Omitting dissenting views or findings

While reviewing the literature, you might discover authors who disagree with your central argument or whose own findings contradict your hypothesis. Don't omit those sources: embrace them! Remember, the literature review aims to explore the academic dialogue around your topic: disagreements or conflicting findings are often part of that dialogue, and including them in your writing will create a sense of rich, critical engagement. In fact, highlighting any disagreements amongst scholars is a great way to emphasise the relevance of, and need for, your own research.

Miscalculating the scope

As shown in the funnel structure (see 'Structure' tab for more), a literature review often starts broadly and then narrows the dialogue as it progresses, ultimately bringing the reader to the dissertation's specific research topic (e.g. the funnel's narrowest point).

Within that structure, it's common for writers to miscalculate the scope required. They might open the literature review far too broadly, dedicating disproportionate space to developing background information or general theory; alternately, they might rush into the narrowest part of the discussion, failing to develop any sense of surrounding context or background, first.

It takes trial and error to determine the appropriate scope for your literature review. To help with this...

- Imagine your literature review subtopics cascading down a stairwell, as in the illustration below.

- Place the broadest concepts on the highest steps, then narrow down to the most specific concepts on the lowest steps: the scope 'zooms in' as you move down the stairwell.

- Now, consider which step is the most logical starting place for your readers. Do they need to start all the way at the top, or should you 'zoom in'?

The illustration above shows a stairwell diagram of a dissertation that aims to analyse Stephen King's horror novel The Stand through the lens of a specific feminist literary theory.

- If the literature review began on one of the bottom two steps, this would feel rushed and inadequate. The writer needs to explore and define the relevant theoretical lens before they discuss how it has been applied by other scholars.

- If the literature review began on the very top step, this would feel comically broad in terms of scope: in this writing context, the reader doesn't require a detailed account of the entire history of feminism!

The third step, therefore, represents a promising starting point: not too narrow, not too broad.

The 'islands' structure

Above all else, a literature review needs to synthesize a range of sources in a logical fashion. In this context, to synthesize means to bring together, connect, weave, and/or relate. A common mistake writers make is failing to conduct such synthesis, and instead discussing each source in isolation. This leads to a disconnected structure, with each source treated like its own little 'island'. The island approach works for very few projects.

Some writers end up with this island structure because they confuse the nature of the literature review with the nature of an annotated bibliography . The latter is a tool you can use to analyse and keep track of individual sources, and most annotated bibliographies will indeed be arranged in a source-by-source structure. That's fine for pre-writing and notetaking, but to structure the literature review, you need to think about connections and overlaps between sources rather than considering them as stand-alone works.

If you are struggling to forge connections between your sources, break down the process into tiny steps:

- e.g. Air pollution from wood-burning stoves in homes.

- e.g. Bryant and Dao (2022) found that X% of small particle pollution in the United Kingdom can be attributed to the use of wood-burning stoves.

- e.g. A study by Williams (2023) reinforced those findings, indicating that small particle pollution has...

- e.g. However, Landers (2023) cautions that factor ABC and factor XYZ may contribute equally to poor air quality, suggesting that further research...

The above exercise is not meant to suggest that you can only write one sentence per source: you can write more than that, of course! The exercise is simply designed to help you start synthesizing the literature rather than giving each source the island treatment.

Q: I still don't get it - what's the point of a literature review?

A: Let's boil it down to three key points...

- The literature review provides a platform for you, as a scholar, to demonstrate your understanding of how your research area has evolved. By engaging with seminal texts or the most up-to-date findings in your field, you can situate your own research within the relevant academic context(s) or conversation(s).

- The literature review allows you to identify the research gap your project addresses: in other words, what you will add to discussions in your academic field.

- Finally, the literature review justifies the reason for your research. By exploring existing literature, you can highlight the relevance and purpose of your own research.

Q: What if I don't have a gap?

A: It's normal to struggle with identifying a research gap. This can be particularly true if you are working in a highly saturated research area, broadly speaking: for example, if you are studying the links between nutrition and diabetes, or if you are studying Shakespeare.

The 'What to Avoid' tab explained that miscalculating the scope is a common mistake in literature reviews. If you are struggling to identify your gap, scope might be the culprit, particularly if you are working in a saturated field. Remember that the gap is the narrowest part of the funnel, the smallest nesting doll, the lowest step: this means your contribution in that giant academic conversation will need to be quite 'zoomed in':

This is not a valid gap → Analysing Shakespeare's sonnets.

This might be a valid gap → Conducting an ecocritical analysis of the visual motifs of Shakespeare's final five procreation sonnets (e.g. sonnets number thirteen to seventeen).

In the above example, the revised attempt to articulate a gap 'zooms in' by identifying a particular theoretical lens (e.g. ecocriticism), a specific convention to analyse (e.g. use of visual motifs), and a narrower object (e.g. five sonnets rather than all 150+). The field of Shakespeare studies might be crowded, but there is nonetheless room to make an original contribution.

Conversely, it might be difficult to identify the gap if you are working not in a saturated field, but in a brand new or niche research area. How can you situate your work within a relevant academic conversation if it seems like the 'conversation' is just you talking to yourself?

In these cases, rather than 'zooming in', you might find it helpful to 'zoom out'. If your topic is niche, think creatively about who will be interested in your results. Who would benefit from understanding your findings? Who could potentially apply them or build upon them? Thinking of this in interdisciplinary terms is helpful for some projects.

Tip: Venn diagrams and mind maps are great ways to explore how your research connects to, and diverges from, the existing literature.

Q: How many references should I use in my literature review?

A: This question is risky to answer because the variations between individual projects and disciplines make it impossible to provide a universal answer. The fact is that one dissertation might have 50 more references than another, yet the two projects could be equally rigorous and successful in fulfilling their research aims.

With that warning in mind, let's consider a 'standard' dissertation of around 10K words. In that context, referencing 30 to 40 sources in your literature review tends to work well. Again, this is not a universally accurate rule, but a ballpark figure for you to contemplate. If the 30 to 40 estimate seems frighteningly high to you, do remember that many sources will be used sparingly rather than being mulled over at length. Consider this example:

In British GP practices, pharmaceutical treatment is most often prescribed for Health Condition XYZ ( Carlos, 2019; Jones, 2020 ; Li, 2022 ). Lifestyle modifications, such as physical exercise or meditation practices, have only recently...

When writing critically, it's important to validate findings across studies rather than trusting only one source. Therefore, this writer has cited three recent studies that agree about the claim being made. The writer will delve into other sources at more length, but here, it makes sense to cite the literature and move quickly along.

As you search the databases and start following the relevant trails of 'research bread crumbs', you will be surprised how quickly your reference list grows.

Q: What if there isn't enough relevant literature on my topic?

A: Think creatively about the literature you are using and engaging with. A good start is panning out to consider your topic more broadly: you might not identify articles that discuss your exact topic, but what can you discover if you shift your focus up one level?

Imagine, for example, that Norah is researching how artificial intelligence (AI) can be used to provide dance instruction. She discovers that no one has written about this topic. Rather than panicking, she breaks down her research question into its component parts to consider what research might exist.

- First, dance instruction: literature on how dance has traditionally been taught (i.e., not with AI) is still relevant because it will provide background and context. To appreciate the challenges or opportunities that transition to AI instruction might bring, we need to understand the status quo. Norah might also search for articles that analyse how other technological shifts have affected dance instruction: for example, how YouTube popularized at-home dance study, or how live video services like Zoom enabled real-time interaction between dance pupils and teachers despite physical distance.

- Next, artificial intelligence used for instruction: Norah can seek out research on, and examples of, the application of AI for instructive purposes. Even if those purposes don't involve dance, such literature can contribute to illustrating the broader context around Norah's project.

- Could it be relevant to discuss the technologies used to track an actor's real-life movements and convert them into the motions of a video game character? Perhaps there are parallels!

- Could it be relevant to explore research on applications of AI in creative writing and visual art? Could be relevant since dance is also a creative field!

In summary, don't panic if you can't find research on your exact question or topic. Think through the broader context and parallel ideas, and you will soon find what you need.

Q: What if my discipline doesn't require a literature review chapter?

A: This is a great question. Whilst many disciplines dictate that your dissertation should include a chapter called Literature Review , not all subjects follow this convention. Those subjects will still expect you to incorporate a range of external literature, but you will nest the sources under different headings.

For example, some disciplines dictate an introductory chapter that is longer than average, and you essentially nest a miniature literature review inside the introduction, itself. Although the writing is more condensed and falls under a subheading of the introduction, the techniques and principles of writing a literature review (for example, moving from the broad to the narrow) will still prove relevant.

Some disciplines include chapters with names like Background , History , Theoretical Framework , etc. The exact functions of such chapters differ, but they have this in common: reviewing literature. You can't provide a critical background or history without synthesizing external sources. To illustrate your theoretical framework, you need to synthesize a range of literature that defines the theory or theories you intend to use.

Therefore, as stated earlier in this guide, you should be prepared to review and synthesize a range of literature regardless of your discipline. You can tailor the purpose of that synthesis to the structure and demands of writing in your subject area.

Q: Does my literature review need to include every source I plan to use in my discussion chapter?

A: The short answer is 'no' - there are some situations in which it is okay to use a source in your discussion chapter that you didn't integrate into your literature review chapter.

Imagine, for example, that your study produced a surprising result: a finding that you didn't anticipate. To make sense of that result, you might need to conduct additional research. That new research will help you explain the unexpected result in your discussion chapter.

More often, however, your discussion will draw on, or return to, sources from your literature review. After all, the literature review is where you paint a detailed picture of the conversation surrounding your research topic. Thus, it makes sense for you to relate your own work to that conversation in the discussion.

The literature review provides you an opportunity to engage with a rich range of published work and, perhaps for the first time, critically consider how your own research fits within and responds to your academic community. This can be a very invigorating process!

At the same time, it's likely that you will be juggling more academic sources than you have ever used in a single writing project. Additionally, you will need to think strategically about the focus and scope of your work: figuring out the best structure for your literature review might require several rounds of re-drafting and significant edits.

If you are usually a 'dive in without a plan and just get drafting' kind of writer, be prepared to modify your approach if you start to feel overwhelmed. Mind mapping, organising your ideas on a marker board, or creating a bullet-pointed reverse outline can help if you start to feel lost.

Alternately, if you are usually a 'create a strict, detailed outline and stick to it at all costs' kind of writer, keep in mind that long-form writing often calls for writers to modify their plans for content and structure as their work progresses and evolves. It can help such writers to schedule periodic 'audits' of their outlines, with the aim being to assess what is still working and what else needs to be added, deleted or modified.

Here’s a final checklist for writing your literature review. Remember that not all of these points will be relevant for your literature review, so make sure you cover whatever’s appropriate for your dissertation. The asterisk (*) indicates any content that might not be relevant for your dissertation. You can save your own copy of the checklist to edit using the Word document, below.

- Literature review self-evaluation checklist

- << Previous: Research Question

- Next: Methodology >>

- Last Updated: Dec 6, 2024 1:46 PM

- URL: https://library.soton.ac.uk/writing_the_dissertation

IMAGES