ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Adolescents’ mental health at school: the mediating role of life satisfaction.

- Lab for Developmental and Educational Studies in Psychology, “R. Massa” Department of Human Sciences for Education, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

In this study, we further developed prior research on risk and protective factors in adolescents’ mental health. More specifically, we used structural equation modelling to assess whether relationships at school with teachers and peers, and life satisfaction predicted mental health in a large sample of adolescents, while also testing for age and gender invariance. The sample comprised 3,895 adolescents ( M age = 16.7, SD = 1.5, 41.3% girls), who completed self-report instruments assessing their perceived life satisfaction, student-teacher relationship, school connectedness and mental health. Overall, the results suggested that life satisfaction acted as a mediator between adolescents’ positive school relations and their mental health. Outcomes were invariant across genders, while quality of school relations and mental health declined with age. Limitations of the study and futures lines in mental health research among adolescents are briefly discussed.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, mental health is ‘ a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, copes with the normal stresses of life, works productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community ’ ( World Health Organization, 2005 , p. 12). This definition recognises mental health as a dimension of overall health that spans a continuum from high-level wellness to severe illness, emphasising the key role of positive feelings, a sense of mastery and positive functioning ( Galderisi et al., 2015 ).

Adolescence is widely known to be a sensitive period of exposure to a range of mental disorders whose incidence has been increasing in recent decades ( Patton et al., 2014 ; Erskine et al., 2015 ). Indeed, approximately 20% of school students are now affected by diagnosable mental illnesses, with half of all mental issues developing by 14 years ( Ford et al., 2003 ; Gore et al., 2011 ). Data from studies with adolescents indicate that anxiety, depression, eating disorders, bipolar disorder, personality disorders, psychosis, addictive disorders, substance abuse, suicide attempts and self-harm are all becoming more frequent among this demographic ( Paus et al., 2008 ; Twenge et al., 2018 ; Burstein et al., 2019 ). In most cases, disorders of this kind remain undetected and, consequently, untreated until later in life ( Kessler et al., 2007 ; Patel et al., 2007 ). Furthermore, depression in young people is a highly prevalent illness worldwide, and suicide is the third most frequent cause of death among adolescents in the United States and Europe ( World Health Organization, 2012 ; Keyes et al., 2019 ; Twenge, 2020 ).

The literature shows that adolescent mental health is influenced by both individual attributes and the everyday life contexts where adolescents grow up, including school, which is a key developmental setting ( Weare and Nind, 2011 ; Cefai and Cavioni, 2015 ). Students who experience mental health difficulties at school tend to exhibit poor school adjustment, reduced concentration, low achievement, problematic social relationships and a higher rate of health risk behaviours, such as substance use, school dropout and incurring expulsion ( Valdez et al., 2011 ; Suldo et al., 2014 ; Farina et al., 2021 ).

Recent research also suggests that older adolescents may suffer a decline in mental health outcomes, with older girls reporting poorer mental health than older boys ( Inchley et al., 2020 ). This evidence has led to growing awareness of the need to address adolescents’ mental health requirements by identifying the factors that can promote or hinder their mental health in the school setting ( Eccles and Roeser, 2011 ; Cavioni et al., 2020a ). Accordingly, the aim of this study was to investigate the role of life satisfaction and school relations, as protective and risk factors for mental health, in a large sample of adolescents.

Protective and Risk Factors Associated with School Mental Health in Adolescence

Protective factors for mental health may be defined as individual and environmental characteristics that foster healthy development but also reduce the negative impact of risk factors for mental health issues ( Deković, 1999 ; O’Connell et al., 2009 ). In contrast, mental health risk factors can increase a person’s chances of developing psychological illness ( World Health Organization, 2012 ). In this research, we examined three factors that impact on adolescents’ mental health. The first is an individual factor, life satisfaction, while the second and third are school contextual factors, namely, student-teacher relationship and sense of community at school. Indeed, the literature on adolescent mental health is notably lacking in research on how the contextual factors associated with quality of school relationships interact with individual characteristics, such as life satisfaction, to shape mental health outcomes ( Torsheim and Wold, 2001 ; Craig et al., 2020 ). In the next section, we review the existing research findings for each of these key factors.

Individual Factor: Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction is defined as ‘the global assessment of a person’s quality of life according to his own chosen criteria’ ( Andrews and Withey, 1976 , p. 478). Numerous studies have found that adolescents with higher levels of life satisfaction display better school adaptive functioning, in terms of self-efficacy, self-esteem, engagement, academic achievement, social acceptance and peer relationships, as well as lower levels of school absenteeism, dropout and behavioural problems ( Proctor et al., 2009 ; Fergusson et al., 2015 ). Conversely, adolescents with low life satisfaction are more likely to display internalising and externalising problems, social stress and substance abuse ( Zullig et al., 2001 ; Haranin et al., 2007 ).

Contextual Factors: Student-Teacher Relationship and Sense of Community at School

At the contextual level, multiple school-related factors have been associated with positive mental health outcomes in adolescents. More specifically, student-teacher relationship and sense of school community are known to serve as key protective factors via the provision of emotional and social support and safe environments ( Eccles and Roeser, 2011 ). Overall, such contextual factors are associated with a lower likelihood of negative mental health outcomes, such as perceived stress, health complaints and unhealthy behavior ( Lemma et al., 2014 ). In turn, adolescents with better mental health tend to display higher levels of attainment, decision-making ability, problem-solving skills and academic achievement ( Bonell et al., 2014 ; Suldo et al., 2014 ).

With regard to the student-teacher relationship, past research has generally assessed its positive and negative aspects and their implications for a wide range of student mental health outcomes. For example, Murray and Greenberg (2001) proposed that the relationship is formed of four components. Two concern the positive aspects of the relationship, which are affiliation with the teacher and a sense of bonding with school, and two its negative characteristics, which are dissatisfaction with the teacher and perceived school dangerousness. Studies on the positive aspects of the student-teacher relationship have shown that when it is characterised by warmth, respect, support and openness, it can have positive effects on students’ attitudes towards school, fostering an increased sense of belonging and more effective learning ( Doll et al., 2004 ; Suldo et al., 2009 ). Pianta and colleagues have extensively documented the relationship between higher levels of attachment to teachers and bonding with the school and enhanced social and emotional skills, school satisfaction, engagement and motivation on the part of the students (e.g. Pianta, 1999 ; Pianta et al., 2003 ; Pianta and Hamre, 2009 ). During adolescence, affiliation with teachers and bonds with the school can shield young people from the effects of stressful life events, promoting resilience and decreasing the likelihood of developing mental health issues, such as depression and misconduct ( Murray and Greenberg, 2001 ; Wang et al., 2013 ; Lemma et al., 2014 ; Cefai et al., 2015 , 2018 ; Höltge et al., 2021 ). In contrast, dissatisfaction with teachers and perceived school dangerousness bear the potential to negatively affect mental health outcomes ( Mameli et al., 2018 ). Indeed, studies with adolescents suggest that higher levels of dissatisfaction with teachers are associated with poor social functioning and increased peer problems, anxiety and somatic symptoms ( Mameli et al., 2018 ), whereas perceptions of poor school safety are linked with internalising and externalising behavior problems and bullying ( Nijs et al., 2014 ).

The sense of community in a school, also termed ‘school connectedness’ or ‘belongingness in the school’, is the other contextual factor that we view as a significant marker for mental health. It may be defined as ‘the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the school social environment’ ( Goodenow, 1993 , p. 80). Numerous scholars have examined the impact of sense of community on adolescent mental health, finding that school connectedness is positively associated with healthy behaviours, school engagement and adjustment, motivation, school attendance, conflict resolution skills and prosocial behavior ( Vieno et al., 2005 ; Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009 ). Conversely, sense of community is negatively associated with school absenteeism, loneliness, worry, social isolation, emotional distress, antisocial and risky behaviours, violence, delinquency, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts ( Hirschi, 1969 ; Pretty et al., 1994 ; Joyce and Early, 2014 ).

Age and Gender Differences in Mental Health Outcomes

Cohort studies with adolescent samples indicate that the incidence of mental health disorders increases with age, especially emotional and conduct disorders, and psychosomatic problems ( Bell et al., 2019 ). According to the recent Health Behavior in School-aged Children report, adolescents’ quality of school relationships and school belonging worsen over time. In contrast, younger adolescents report higher levels of life satisfaction and better mental health ( Inchley et al., 2020 ).

With respect to gender, research has long shown that adolescent males and females tend to display different mental health patterns in relation to internalising and externalising behavioural problems ( Yeo et al., 2007 ; Nijs et al., 2014 ). For example, various studies have found that girls display more frequent and intense internalising behaviours, such as stress and anxiety (e.g. concerning interpersonal relationships, school demands, family relationships, and personal and social adjustment), as well as a higher risk of developing depression compared to males ( Angold and Rutter, 1992 ; Compas et al., 1993 ; Nolen-Hoeksema and Girgus, 1994 ). On the contrary, male adolescents are more prone to externalising behaviours, such as school problems, aggressive behavior and difficulty in managing negative emotions ( Stark et al., 1989 ; van der Ende and Verhulst, 2005 ).

Research Aims and Hypothesis

Although the existing research offers insights into the role played by individual and contextual factors in secondary school students’ mental health, most previous studies have taken a deficit-based approach by focusing on the impact of negative factors ( Ben-Arieh, 2000 ; Antaramian et al., 2010 ). Consequently, a number of authors have pointed out the need to focus on the role of both risk and protective factors and how they simultaneously impact on mental health (e.g. Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000 ; Terjesen et al., 2004 ). Furthermore, despite growing awareness of the importance of relational experience at school, relatively few studies have focused on the quality of students’ social relationships with teachers and peers and its impact on overall mental health during adolescence ( Torsheim and Wold, 2001 ; Gaete et al., 2016 ).

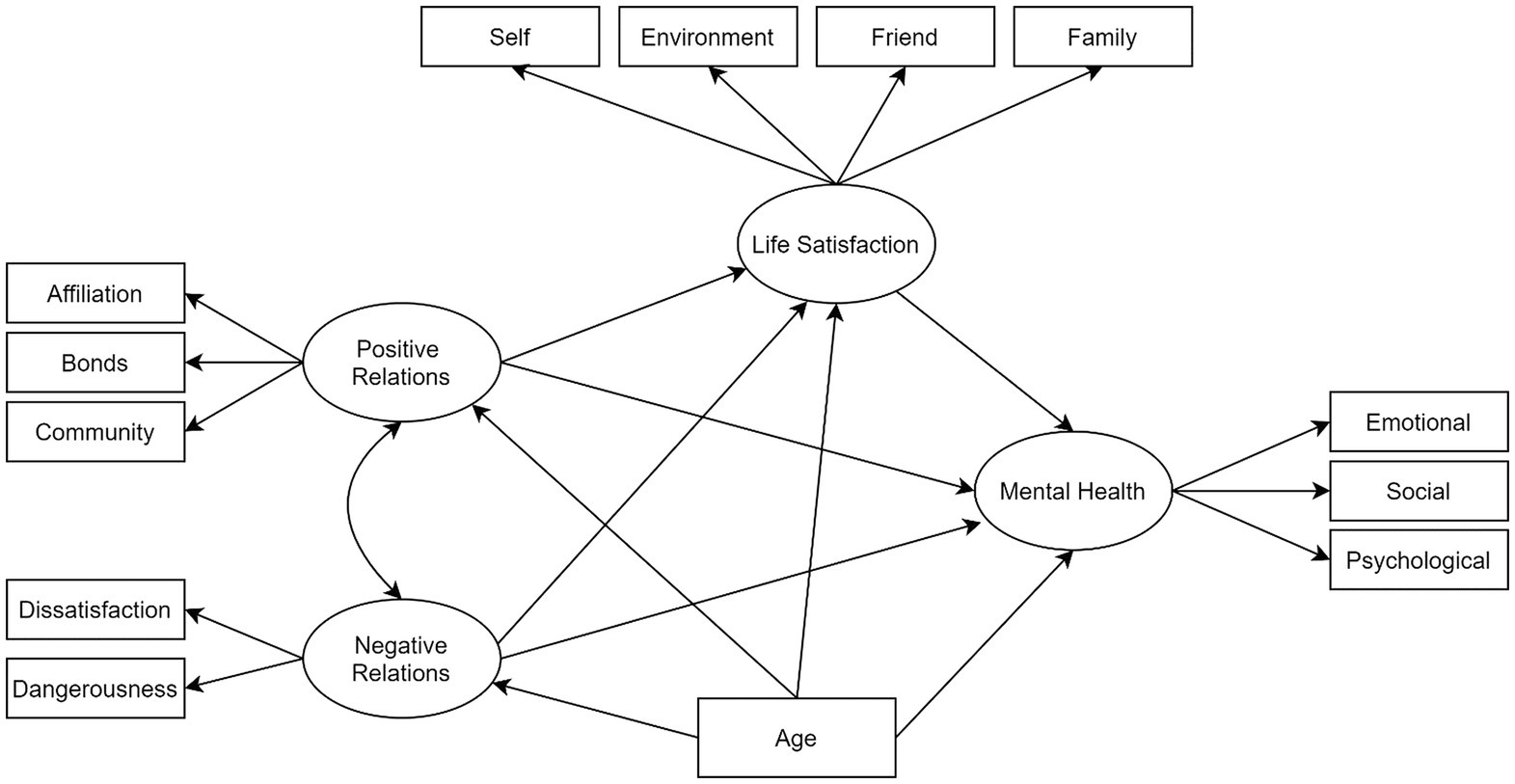

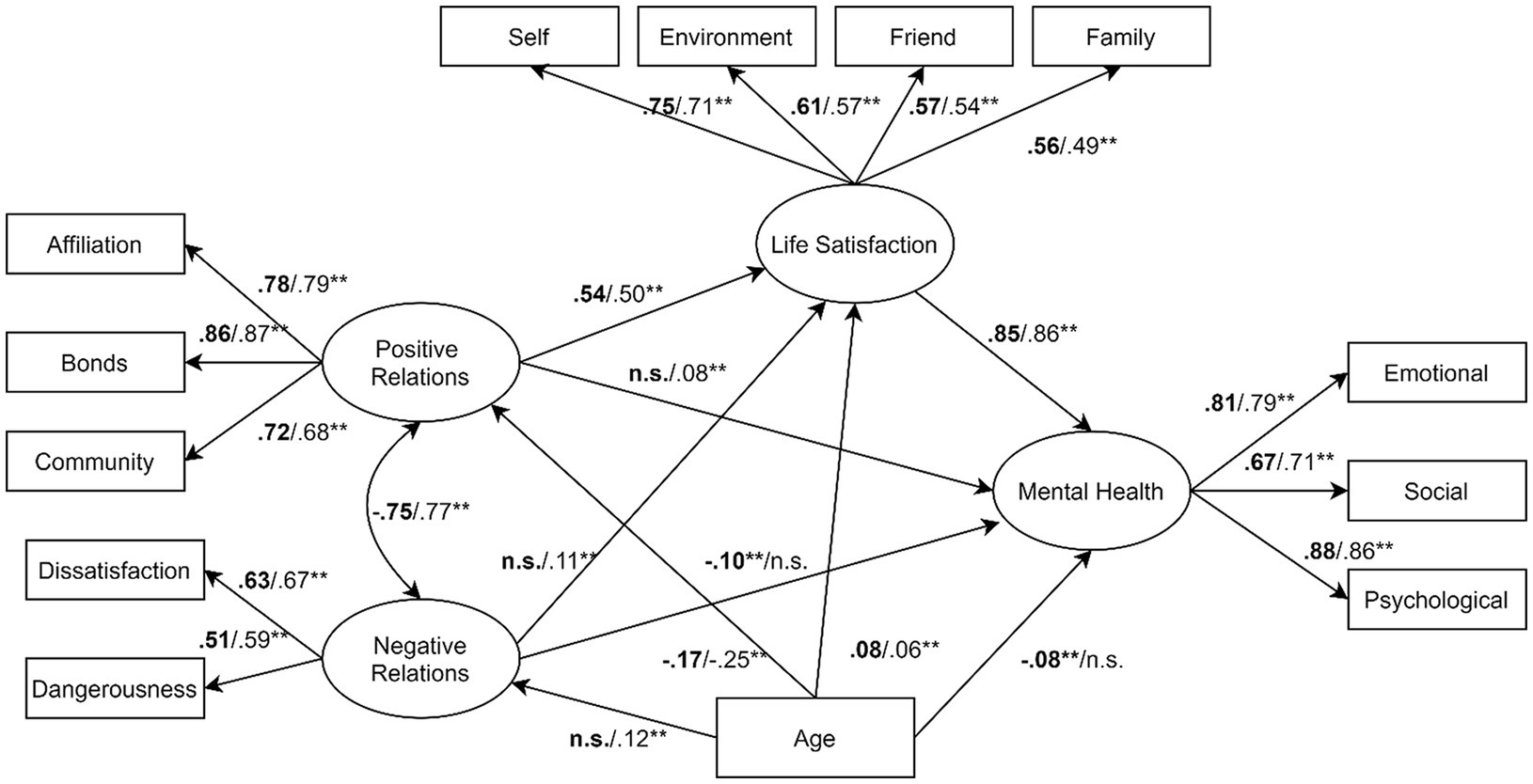

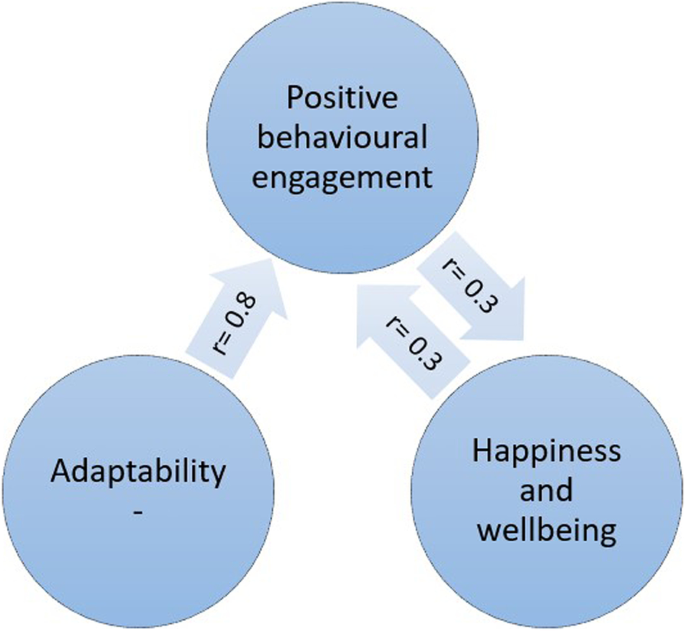

To address this gap, we set out to extend the recent literature on school-related factors in adolescents’ mental health by focusing on both protective and risk factors. More specifically, we used structural equation modelling (SEM) to evaluate the contributions of quality of school relations and life satisfaction to the mental health of a large group of adolescents. The model was also specified to control for effects of age, whereas a multigroup invariance test was conducted to assess differences as a function of gender. The conceptual model is illustrated in Figure 1 .

Figure 1 . Conceptual model of association between type of relationships at school, life satisfaction and mental health in adolescents.

Specifically, we expected that positive relations at school, in terms of affiliation with teachers, bonds with school and sense of school community, would be positively associated with both life satisfaction and mental health (Hypothesis 1); moreover, we predicted that negative relationships, in terms of dissatisfaction with teachers and a perception of school dangerousness, would be negatively associated with both life satisfaction and mental health (Hypothesis 2). In addition, we planned to conduct a multigroup invariance test to assess whether were differences between boys and girls in terms of the magnitude of the predicted associations. Notably, while past studies have examined gender differences in relation to life satisfaction and mental health, little research to date has attempted to model these variables in relation to the quality of young people’s relationships at school.

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedures.

The head teachers of 20 high schools located in two regions of Northern Italy (Lombardy and Piedmont) were contacted via email or by telephone and informed about the aims of the study and the research procedure. Seventeen schools agreed to participate in the study. A briefing letter was sent to the students’ parents. Informed consent and GDPR consent were obtained from all respondents and from their parents (who were free to deny their child’s participation in the study). Data were collected anonymously, and students were free to withdraw at any time during the administration of the questionnaire. Seventeen parents refused permission for their child to participate in the study; 11 students were absent during data collection, and four declined to participate.

Students responded to a set of online questionnaires in the classroom during regular school hours. The entire battery of instruments took about 15 min to complete. The questionnaires were presented in random order to minimise potential sources of measurement error ( Franke, 1997 ). Data collection was managed by the lead researcher and two research assistants, who presented the aims of the study to the students before administering the questionnaires.

A sample of 3,895 students (41.3% girls) completed the research instruments. Following a review of missing data, no questionnaires were removed from the analysis due to the use of mandatory fields in the online data collection. The final sample, aged between 15 and 19 years ( M = 16.7, SD = 1.5), included students from all three branches of the Italian high school system: professional institutes, technical institutes and lyceums. Almost half the participants (48%) were enrolled at lyceums (academic track), compared to 25.1 and 26.9% who attended professional and technical schools (vocational track), respectively. The majority (88.7%) were Italian citizens (i.e., born in Italy of Italian parents), while 11.3% came from non-Italian ethno-cultural backgrounds (parents not Italian and/or not born in Italy). The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Milano-Bicocca University and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Demographics

Participants were asked to specify their age, gender, school grade and nationality.

Life Satisfaction

The Italian translation of the abbreviated Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS) was used to assess life satisfaction ( Huebner, 1994 ; Huebner et al., 1998 ; Zappulla et al., 2014 ). The MSLSS is a thirty-item self-report questionnaire that measures children’s and adolescents’ life satisfaction in five domains: family (e.g. ‘I enjoy being at home with my family’), friends (e.g. ‘My friends treat me well’), school (e.g. ‘I look forward to going to school’), self (e.g. ‘Most people like me’) and living environment (‘My family’s house is nice’). Respondents are asked to rate items on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Previous studies with adolescent samples yielded acceptable validity and reliability coefficients across the five domains with alphas ranging from 0.71 to 0.91 ( Gilligan and Huebner, 2007 ; Sawatzky et al., 2009 ; Huebner et al., 2012 ; Zappulla et al., 2014 ). Cronbach’s reliability values for the present study were as follows: family ( α = 0.89), friend ( α = 0.85), environment ( α = 0.75), self ( α = 0.73) and school ( α = 0.79).

Student-Teacher Relationship

Students’ perceptions of their relationships with teachers and bonds with school were evaluated using the Italian version of the Student-Teacher Relationship Questionnaire (STRQ; Tonci et al., 2012 ) developed by Murray and Greenberg (2001) . The STRQ comprises 22 items to be rated on a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 = almost never or never true to 4 = almost always or always true). The questionnaire evaluates the quality of individual students’ relationships with their teachers and their perceptions of their school environment in terms of four factors: affiliation with teacher (e.g. ‘My teachers pay a lot of attention to me’), dissatisfaction with teachers (e.g. ‘I feel angry with my teacher’), bonds with school (e.g. ‘I feel safe at my school’) and school dangerousness (e.g. ‘My school is a dangerous place to be’). The four factors have been found to be reliable, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging between 0.66 and 0.88 ( Murray and Greenberg, 2001 ). Cronbach’s reliability values in the present study were as follows: affiliation ( α = 0.84), bonds ( α = 0.71), dangerousness ( α = 0.66) and dissatisfaction ( α = 0.74).

Sense of Community in School

Students’ sense of community was assessed via the Italian version of the Students’ Sense of Community in School scale ( Vieno et al., 2005 ), originally developed by Samdal et al. (1998) . The questionnaire comprises six items (e.g. ‘I feel I belong at this school’) designed to assess the three dimensions of sense of community (membership, shared emotional connection and fulfilment of needs) identified by McMillan and Chavis (1986) . Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). In previous studies, this questionnaire displayed satisfactory internal reliability with alphas ranging between 0.71 and 0.82 ( Vieno et al., 2005 ; Prati et al., 2020 ). Cronbach’s reliability value for the present study was α =0.75.

Mental Health

The Italian validated version of the Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF) was used to assess respondent’ mental health ( Petrillo et al., 2015 ). This instrument, originally developed by Keyes (2002) , is a self-report questionnaire comprising 14 items. Informed by Keyes’ theoretical model of mental health ( Keyes, 1998 , 2002 , 2005 , 2007 ; Keyes and Waterman, 2003 ), the MHC-SF evaluates three dimensions of mental health: emotional (e.g. ‘How often did you feel happy?’), social (e.g. ‘How often did you feel that you had something important to contribute to society?’) and psychological (e.g. ‘How often did you feel good at managing the responsibilities of your daily life?’). Items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time), based on respondents’ experience over the preceding month. Total scores on the MHC-SF range from 0 to 70, with higher scores reflecting better mental health. Among adolescents, the MHC-SF has displayed validity and satisfactory internal reliability values ranging from 0.75 to 0.91 ( Lim, 2014 ; Petrillo et al., 2014 , 2015 ; Luijten et al., 2019 ; Reinhardt et al., 2020 ). Cronbach’s reliability values for the present study were as follows: emotional ( α = 0.81), social ( α = 0.78) and psychological ( α = 0.83).

Statistical Analysis and SEM

In order to test the network of associations between adolescents’ mental health and the other study variables, we adopted a SEM approach ( Thakkar, 2020 ). SEM techniques are based on multivariate data analysis and combine empirical measurement with theoretical inquiry by allowing latent factors to be estimated along with patterns of associations among observed variables ( Guo et al., 2009 ; Cavioni et al., 2020b ; Farina et al., 2020 ; Veronese et al., 2020 ). SEM permits estimation of the magnitude and direction of paths among variables and the evaluation of total, direct and indirect effects ( Hair et al., 2017 ).

It is essentially a method of testing hypotheses via a confirmatory rather than an exploratory approach. In the present paper, we estimated a model with four latent variables and 13 empirical indicators (see Figure 1 ).

Moving from left to right in the figure, two of the latent constructs were positive and negative school relationships as operationalised by five empirical indicators: affiliation with teachers, bonds with school, sense of community, dissatisfaction with school and school dangerousness. Next, life satisfaction was assessed in relation to four domains: self, friends, family and environment. The school domain of the MSLSS was omitted from the analysis due to its collinearity with other latent variables (e.g. positive and negative school relations ). Finally, the target latent variable mental health was modelled via its psychological, emotional and social dimensions. In line with the research hypotheses, we estimated the direct effects of positive and negative school relations on both life satisfaction and mental health. All variables were viewed as endogenous conceptual components of the model, whereas participants’ age was modelled as an exogenous variable. Estimated total effects were broken down into direct and indirect effects ( Kline, 2015 ).

Following standard procedures for SEM, we evaluated the following goodness-of-fit indices: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; RMSEA < 0.05; Madeu-Olivares et al., 2018 ), standardised root mean square residual (SRMR; SRMR < 0.05) ( Sass et al., 2014 ); normed fit index (NFI; NFI > 0.95; Marsh et al., 2013 ), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; TLI > 0.95; Morin et al., 2013 ) and comparative fit index (CFI; CFI > 0.95; Morin et al., 2013 ). As currently recommended (e.g. Bollen and Long, 1993 ; Kaplan and Depaoli, 2012 ) for SEM, we used both Monte Carlo simulation and bootstrapping methods to estimate confidence limits with a set of random samples ( k = 500). We calculated the given indirect effects for each of the k samples and the mean value for the selected pool of samples. Finally, we conducted a multigroup invariance test (MGCFA) to determine whether similar response patterns were obtained across gender-based cohorts. The MGCFA also helped us to specify the model structure with the best potential for generalisation ( Brown et al., 2017 ). The hypothesis of measurement invariance was to be accepted if configural invariance (all parameters free to vary but structural model held constant), metric invariance (factor loadings set to be equal in both groups), scalar invariance (factor loadings and item intercepts constrained) and full invariance (all parameters were equivalent across the groups) were all supported. Structural equivalence was to be rejected if the indexed variations were statistically significant. The cut-off points (CFI, RMSEA and SRMR) for rejecting measurement invariance were set at Δ = 0.01, corresponding to a p level of 0.01 ( Chen, 2007 ).

We also estimated Mahalanobis’ distance ( p < 0.001) to detect potentially multivariate outliers; no cases needed to be removed from the dataset. Finally, we assessed the distribution of the data for each of the study measures. None of the kurtosis or skewness values exceeded the recommended limits [−1,+1], and consequently, the maximum likelihood method ( Gath and Hayes, 2006 ) was adopted to estimate the parameters for the SEM analysis. The software used for all analyses was Amos 23.0 ( Arbuckle, 2014 ).

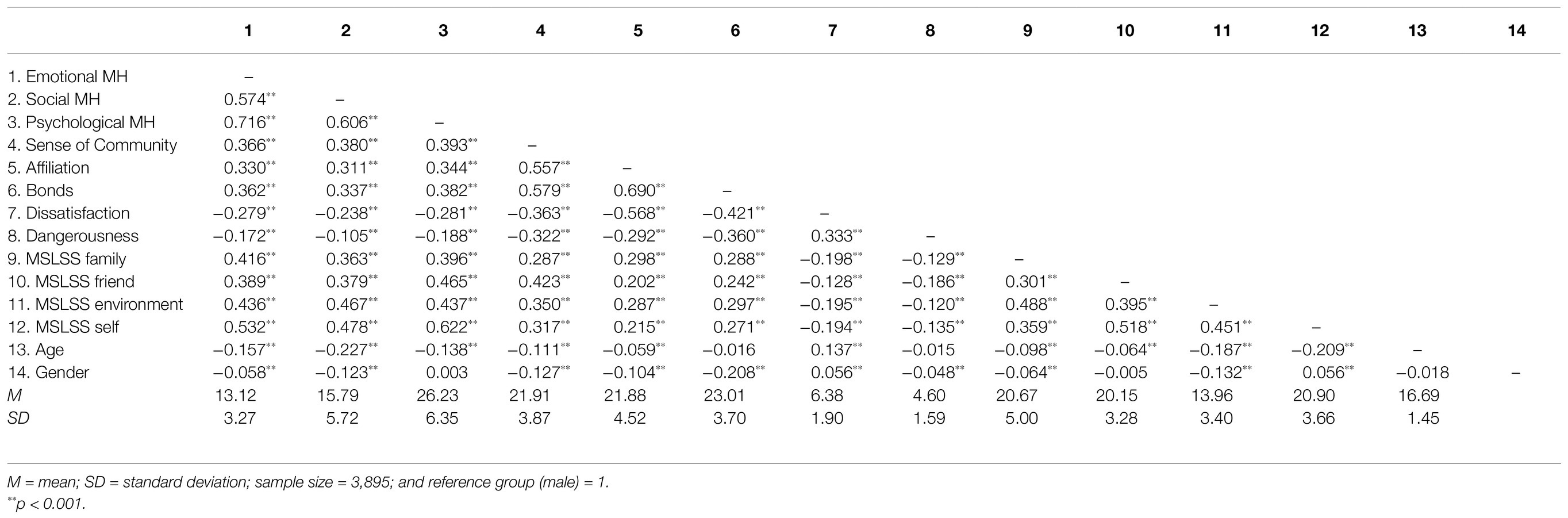

Table 1 provides a summary of the main descriptive statistics for the variables under study (e.g. mean values and standard deviations), along with their zero-order correlations.

Table 1 . Zero-order correlations and main descriptive statistics for mental health, life satisfaction and positive/negative school relations.

In general, the zero-order correlations revealed statistically significant, robustly positive patterns of association between mental health and positive school relations, with r values ranging between 0.382 (psychological mental health and bonds) and 0.311 (social mental health and affiliation). Furthermore, mental health was negatively associated with negative relations, with an especially robust association between dissatisfaction and the psychological dimension of mental health. However, the strongest patterns of association in terms of statistical significance and magnitude of effect were observed between mental health and life satisfaction, with values ranging between 0.622 (psychological mental health and satisfaction with self) and 0.379 (social mental health and satisfaction with friends). With regard to demographic variables, age was found to be negatively associated with all aspects of mental health and life satisfaction, while mixed patterns of association were found between age and school relations. Concerning gender differences, zero-order correlations were generally low or not statistically significant, with the exception of bonds with school ( r = −0.108), a measure on which boys scored more poorly than girls. Overall, the correlational analysis provided support for testing a structural equation model with all the study variables.

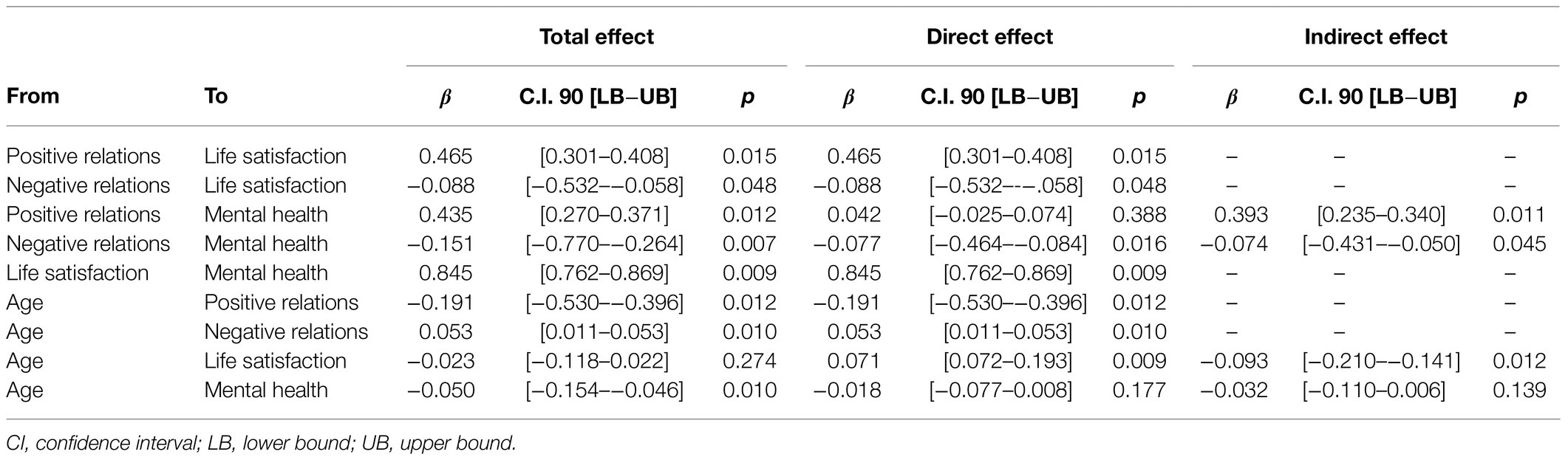

The fit analysis (see Figure 1 ) suggested that the empirical data provided a good fit for conceptual model. All the fit indexes endorsed the full acceptance of the model: NFI = 0.954, NNFI = 0.954, CFI = 0.956, RMSEA = 0.066 [C.I. 90th = 0.063–0.070] and SRMR = 0.041. Total, direct and indirect standardised effects are reported in Table 2 . Indirect effects reflect interaction among three variables, while a direct effect represents the impact of a single determinant on a given target variable.

Table 2 . Breakdown of total, direct and indirect standardised effects identified via the structural model.

Again, moving from left to right, the latent variable, positive school relations, had significant effects on both life satisfaction ( β = 0.478) and mental health ( β = 0.435). Interestingly, the direct pathway between positive relations and mental health was negligible and non-significant ( β = 0.042), meaning that life satisfaction fully mediated the association between these two variables (the magnitude of the indirect effect was 0.393). Negative school relations had significant total effects on both life satisfaction ( β = − 0.088) and mental health ( β = −0.151), although the magnitude of these effects was small compared to the effects of positive relationships. Finally, a large, statistically significant, positive pathway was observed from life satisfaction to mental health ( β = 0.845). In terms of pathways between age and latent variables, older adolescents generally reported weaker positive relations ( β = −0.191), poorer mental health ( β = −0.05) and stronger negative relations ( β = 0.053). In contrast, no statistically significant pathway was found between age and life satisfaction. The results of the invariance test of gender-based cohorts of adolescents are reported in Table 3 and Figure 2 .

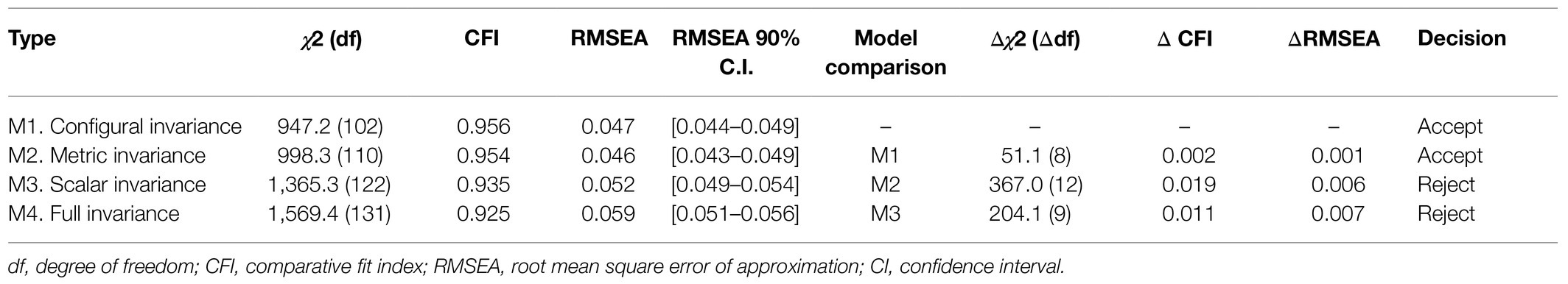

Table 3 . Multigroup analysis of the structural equation model: fit indexes and model comparison.

Figure 2 . Structural model and standardised direct effects as resulting from invariance test ( n = 3,895). ** p < 0.01; n.s. = not statistically significant. Values for males were reported in bold.

The main outcome of the invariance analysis was that the structural equation model supported the first two levels of invariance between boys and girls. Specifically, only configural and metric invariance were confirmed, meaning that the theorised set of variables and pathways held in the two groups, but males and females obtained different intercept values. Although the set of pathways remained substantially the same in the two cohorts of adolescents, there were minor differences concerning the latent variable negative relations: specifically, there was a small inverse association ( β = −0.109) between negative relations and life satisfaction for girls, but this pathway was not statistically significant for boys.

The main aim of the present study was to investigate – via SEM – whether and to what extent quality of school relations and life satisfaction predicted mental health in a large sample of adolescents. We obtained the following key findings, which are discussed below in further detail. First, we found strong associations between the quality of adolescents’ school relations, their life satisfaction and their mental health. Second, life satisfaction, which was positively associated with mental health, was found to act as mediator between adolescents’ positive relationships and their mental health. Third, both the quality of school relations and life satisfaction appeared to protect mental health, and this outcome did not significantly vary as a function of gender. Finally, students’ quality of school relations and mental health deteriorated with age.

Associations Among Quality of School Relations, Life Satisfaction and Mental Health

The first main outcome confirmed our leading research hypothesis, namely that positive school relations, in terms of affiliation with teachers, bond with school and sense of community, would be positively associated with mental health and life satisfaction. The second hypothesis was also borne out by the data: specifically, negative school relations, in terms of dissatisfaction with teachers and perceptions of school dangerousness, were negatively associated with life satisfaction and mental health. The structural equational model also indicated that the quality of school relations – operationalised via affiliation with teachers, bonds with school and sense of community – was associated with adolescents’ mental health. Although the literature acknowledges the importance of students’ social and relational experience, and especially the role of teachers in promoting it (e.g. Pianta, 1999 ; Roorda et al., 2011 ; Cavioni et al., 2017 ), few recent studies have been focused on how these factors may be related to one another during adolescence. Our findings also underscored the key role of student-teacher relationships, especially in the high school setting where they tend to become more impersonal ( Roorda et al., 2011 ). This is in line with recent work by Ibrahim and El Zaatari (2020) , who concluded that teacher-student relationships are the most important relationship in the school context and have positive effects on students’ mental health when characterised by empathy, closeness, love, care, support, respect and reciprocity. Another remarkable outcome of our model concerns the impact of adolescents’ self-perceived bonds with their school and sense of community at school on mental health. Although existing studies have examined the association between adolescents’ school bonds and sense of community on mental health, traditionally the focus has been on their role in reducing emotional and conduct issues, hyperactivity, peer problems, depression and anxiety ( Lester et al., 2013 ; Gaete et al., 2016 ). Our findings, on the other hand, offer the novel insight that students’ school bonds and sense of community actually act as preventive factors. Consequently, mental health in schools needs to be promoted by building collective beliefs, values and expectations among students, teachers and all members of the school community. Overall, these outcomes are consistent with the positive psychology approach, which emphasises the importance of identifying and fostering positive indicators of mental health rather than merely detecting and seeking to mitigate factors that cause psychopathology ( Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000 ; Antaramian et al., 2008 ).

The Moderating Role of Life Satisfaction

Our second finding was that life satisfaction played a key mediating role between adolescents’ positive relationships at school and their mental health. In our model, life satisfaction was operationalised as adolescents’ subjective cognitive appraisal of their quality of life in the domains of self, environment, friends and family. We set out to investigate how contextual factors at school interact with individual characteristics to shape adolescents’ mental health, and our results suggest that life satisfaction, conceptualised as an individual factor, may play a significant part in this process. In addition, although the association between life satisfaction and mental health has been widely examined in adult populations, few studies have explored this aspect among adolescents. Existing research conducted with teenage samples has been focused on life satisfaction as a buffer against negative life events and stress, and the development of externalising and internalising behavioural problems ( McKnight et al., 2002 ; Suldo and Huebner, 2004 ; Sawatzky et al., 2010 ). Our results suggest that life satisfaction for adolescents not only acts as a barrier mitigating the impact of negative events and mental health problems ( Lazarus, 1991 ; Suldo and Huebner, 2004 ) but also represents a key psychological resource through which positive relationships can boost mental health.

Gender Invariance

Overall, we identified minor gender differences in the relative strength of the associations among the variables. Previous studies with adolescents mainly examined the role of gender in terms of differential patterns of internalising and externalising behavioural problems in boys versus girls (e.g. van der Ende and Verhulst, 2005 ). However, in this study, we explored the role of gender by applying a multigroup invariance test to compare the performance of our conceptual model across gender groups ( Ornaghi et al., 2016 ). Our structural equation model was aimed at identifying contextual and individual resources that contribute to mental health rather than comparing psychological symptoms between genders. The results suggested that positive school relations and life satisfaction protect the school mental health of both girls and boys.

Age Invariance

We found that older students reported weaker positive school relations and poorer mental health, along with a higher incidence of negative school relations. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have identified declines over time in adolescents’ mental health outcomes as well as in their perceptions of emotional support from teachers ( Eccles and Roeser, 2011 ; Bayram Özdemir and Özdemir, 2020 ). Given that adolescence is a major life period marked by numerous individual and contextual challenges with the potential to impact on adolescents’ mental health ( Dwivedi and Harper, 2004 ; Grazzani Gavazzi et al., 2011 ), our results add to our understanding of the association between school relations and mental health across age groups, confirming that student mental health hits its lowest point during late adolescence.

Limitation and Future Studies

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, although we analysed data from a large sample of adolescents, the outcomes cannot be generalised to early adolescence nor to adolescents with atypical development. Second, the study was conducted on a sample of adolescents mainly enrolled at lyceums. Consequently, the findings can be generalised with caution to the whole population of high school students attending professional and technical institutes. Third, given that the present data were collected in Italian schools from only two regions, the outcome could not be automatically extended to adolescents from the whole Italian Country.

Finally, while we examined the impact of school relations and life satisfaction on adolescents’ mental health at a single time point, relationships at school are never static. We, therefore, recommend that the future research adopt a longitudinal design to investigate how the contribution of the school relationships to young people’s mental health may evolve over time.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Milano-Bicocca. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

VC has made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the research, to the collection, input, scoring and interpretation of the data, and drafting of the manuscript. IG made a key contribution to designing the research, interpreting the data, drafting and revising the manuscript. VO contributed to interpreting the data and revising the manuscript critically. AA has been involved in collecting the data and revising the manuscript critically. AP made a key contribution to analysing and interpreting the data and in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was co-funded by the Erasmus+ programme of the European Union (Reference number: 606689-EPP_2018-2-IT-PI-POLICY).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Veronica Re and Raffaella Roncoroni who collected the data in schools. We also would like to thank the head teachers and teachers who facilitated the data collection in school as well as the students who join the study and their parents who authorised the students’ participation.

Andrews, F. M., and Withey, S. B. (1976). Social Indicators of Well-Being. New York: Plenum.

Google Scholar

Angold, A., and Rutter, M. (1992). The effects of age and pubertal status on depression in a large clinical sample. Dev. Psychopathol. 4, 5–28. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400005538

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Antaramian, S. P., Huebner, E. S., Hills, K. J., and Valois, R. F. (2010). A dual-factor model of mental health: Toward a more comprehensive understanding of youth functioning. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 80, 462–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01049.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Antaramian, S. P., Huebner, E. S., and Valois, R. F. (2008). Adolescent life satisfaction. Appl. Psychol. 57, 112–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00357.x

Arbuckle, J. L. (2014). Amos 23.0 User’s Guide. Chicago, US: IBM SPSS.

Bayram Özdemir, S., and Özdemir, M. (2020). How do adolescents’ perceptions of relationships with teachers change during upper-secondary school years? J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 921–935. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-01155-3

Bell, S., Audrey, S., Gunnell, D., Cooper, A., and Campbell, R. (2019). The relationship between physical activity, mental wellbeing and symptoms of mental health disorder in adolescents: a cohort study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 16:138. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0901-7

Ben-Arieh, A. (2000). Beyond welfare: Measuring and monitoring the state of children: New trends and domains. Soc. Indic. Res. 52, 235–257. doi: 10.1023/A:1007009414348

Bollen, K. A., and Long, J. S. (eds.) (1993). Testing Structural Equation Models. London, UK: Sage Publications, Inc.

Bonell, C., Humphrey, N., Fletcher, A., Moore, L., Anderson, R., and Campbell, R. (2014). Why schools should promote students’ health and wellbeing. Br. Med. J. 13:g3078. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3078

Brown, G. T., Harris, L. R., O’Quin, C., and Lane, K. E. (2017). Using multi-group confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate cross-cultural research: identifying and understanding non-invariance. Int. J. Res. Meth. Educ. 40, 66–90. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2015.1070823

Burstein, B., Agostino, H., and Greenfield, B. (2019). Suicidal attempts and ideation among children and adolescents in US emergency departments, 2007-2015. JAMA Pediatr. 173, 598–600. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0464

Cavioni, V., Grazzani, I., and Ornaghi, V. (2017). Social and emotional learning for children with learning disability: implications for inclusion. Int. J. Emot. 9, 100–109.

Cavioni, V., Grazzani, I., and Ornaghi, V. (2020a). Mental health promotion in schools: A comprehensive theoretical framework. Int. J. Emot. 12, 65–82.

Cavioni, V., Grazzani, I., Ornaghi, V., Pepe, A., and Pons, F. (2020b). Assessing the factor structure and measurement invariance of the Test of Emotion Comprehension (TEC): a large cross-sectional study with children aged 3-10 Years. J. Cogn. Dev. 21, 406–424. doi: 10.1080/15248372.2020.1741365

Cefai, C., Arlove, A., Duca, M., Galea, N., Muscat, M., and Cavioni, V. (2018). RESCUR Surfing the Waves: an evaluation of a resilience programme in the early years. Pastor. Care Educ. 36, 189–204. doi: 10.1080/02643944.2018.1479224

Cefai, C., and Cavioni, V. (2015). “Mental health promotion in school: An integrated, school-based, whole school,” in Promoting Psychological Well-Being in Children and Families. ed. B. Kirkcaldy (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 52–67.

Cefai, C., Cavioni, V., Bartolo, P., Simões, C., Miljevic-Ridicki, R., Bouilet, D., et al. (2015). Social inclusion and social justice: a resilience curriculum for early years and elementary schools in Europe. J. Multicult. Educ. 9, 122–139. doi: 10.1108/JME-01-2015-0002

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2009). School Connectedness: Strategies for Increasing Protective Factors Among Youth. Atlanta, GA, US: Department of Health and Human Services.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Modeling 14, 464–504. doi: 10.1080/10705510701301834

Compas, B. E., Orosan, P. G., and Grant, K. E. (1993). Adolescent stress and coping: Implications for psychopathology during adolescence. J. Adolesc. 16, 331–349. doi: 10.1006/jado.1993.1028

Craig, B. A., Morton, D. P., Morey, P. J., Kent, L. M., Beamish, P., Gane, A. B., et al. (2020). Factors predicting the mental health of adolescents attending a faith-based Australian school system: A multi-group structural equation analysis. J. Ment. Health 29, 401–409. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2019.1608929

Deković, M. (1999). Risk and protective factors in the development of problem behavior. J. Youth Adolesc. 28, 667–685. doi: 10.1023/A:1021635516758

Doll, B., Zucker, S., and Brehm, K. (2004). Resilient Classrooms: Creating Healthy Environments for Learning. New York, USA: Guilford Press.

Dwivedi, K. N., and Harper, P. B. (2004). Promoting the Emotional Well-Being of Children and Adolescents and Preventing their Mental Ill Health: A Handbook. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Eccles, J. S., and Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. J. Res. Adolesc. 21, 225–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00725.x

Erskine, H., Moffitt, T., Copeland, W., Ferrari, A., Patton, G., Degenhardt, L., et al. (2015). A heavy burden on young minds: The global burden of mental and substance use disorders in children and youth. Psychol. Med. 45, 1551–1563. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002888

Farina, E., Ornaghi, V., Pepe, A., Fiorilli, C., and Grazzani, I. (2020). High school student burnout: Is empathy a protective or risk factor? Front. Psychol. 11:897. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00897

Farina, E., Pepe, A., Ornaghi, V., and Cavioni, V. (2021). Trait emotional intelligence and school burnout discriminate between high and low alexithymic profiles: a study with female adolescents. Front. Psychol. 12:645215. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645215

Fergusson, D. M., McLeod, G. F., Horwood, L. J., Swain, N. R., Chapple, S., and Poulton, R. (2015). Life satisfaction and mental health problems (18 to 35 years). Psychol. Med. 45, 2427–2436. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000422

Ford, T., Goodman, R., and Meltzer, H. (2003). The British child and adolescent mental health survey 1999: The prevalence of DSM-IV disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 42, 1203–1211. doi: 10.1097/00004583-20

Franke, G. H. (1997). “The whole is more than the sum of its parts”: The effects of grouping and randomizing items on the reliability and validity of questionnaires. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 13, 67–74. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.13.2.67

Gaete, J., Rojas-Barahona, C. A., Olivares, E., and Araya, R. (2016). Brief report: Association between psychological sense of school membership and mental health among early adolescents. J. Adolesc. 50, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.04.002

Galderisi, S., Heinz, A., Kastrup, M., Beezhold, J., and Sartorius, N. (2015). Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry 14, 231–233. doi: 10.1002/wps.20231

Gath, E. G., and Hayes, K. (2006). Bounds for the largest Mahalanobis distance. Linear Algebra Appl. 419, 93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.laa.2006.04.007

Gilligan, T. D., and Huebner, S. (2007). Initial development and validation of the multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale–adolescent version. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11482-007-9026-2

Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychol. Sch. 30, 79–90. doi: 10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:1<79::AID-PITS2310300113>3.0.CO;2-X

Grazzani Gavazzi, I., Ornaghi, V., and Antoniotti, C. (2011). Children’s and adolescents’ narratives of guilt: antecedents and mentalization. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 8, 311–330. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2010.491303

Gore, F. M., Bloem, P., Patton, G. C., Joseph, V., Coffey, C., Sawyer, S. M., et al. (2011). Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: A systematic analysis. Lancet 377, 2093–2102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60512-6

Guo, B., Perron, B. E., and Gillespie, D. F. (2009). A systematic review of structural equation modelling in Ssial work research. Br. J. Soc. Work. 39, 1556–1574. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcn101

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., and Thiele, K. O. (2017). Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 45, 616–632. doi: 10.1007/s11747-017-0517-x

Haranin, E. C., Huebner, E. S., and Suldo, S. M. (2007). Predictive and incremental validity of global and domain-based adolescent life satisfaction reports. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 25, 127–138. doi: 10.1177/0734282906295620

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of Delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Höltge, J., Theron, L., Cowden, R. G., Govender, K., Maximo, S. I., Carranza, J. S., et al. (2021). A Cross-country network analysis of adolescent resilience. J. Adolesc. Health 68, 580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.010

Huebner, E. S. (1994). Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychol. Assess. 6, 149–158. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.149

Huebner, E. S., Laughlin, J., Ash, C., and Gilman, R. (1998). Further validation of the multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 16, 118–134. doi: 10.1177/073428299801600202

Huebner, E. S., Zullig, K. J., and Saha, R. (2012). Factor structure and reliability of an abbreviated version of the multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. Child Indic. Res. 5, 651–657. doi: 10.1007/s12187-012-9140-z

Ibrahim, A., and El Zaatari, W. (2020). The teacher–student relationship and adolescents’ sense of school belonging. J. Youth Adolesc. 25, 382–395. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1660998

Inchley, J., Currie, D., Budisavljevic, S., Torsheim, T., Jåstad, A., Cosma, A., et al. (2020). Spotlight on adolescent health and well-being. Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey in Europe and Canada. International report. Vol . 1. Key findings. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Joyce, H. D., and Early, T. J. (2014). The impact of school connectedness and teacher support on depressive symptoms in adolescents: A multilevel analysis. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 39, 101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.02.005

Kaplan, D., and Depaoli, S. (2012). “Bayesian structural equation modeling,” in Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling. ed. R. H. Hoyle (New York, US: The Guilford Press), 650–673.

Kessler, R. C., Angermeyer, M., Anthony, J. C., De Graaf, R. O. N., Demyttenaere, K., Gasquet, I., et al. (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s world mental health survey initiative. World Psychiatry 6, 168–176.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Keyes, C. L. (1998). Social well-being. Soc. Psychol. Q. 61, 121–140. doi: 10.2307/2787065

Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 43, 207–222. doi: 10.2307/3090197

Keyes, C. L. (2005). The subjective well-being of America’s youth: Toward a comprehensive assessment. Adolesc. Fam. Health 4, 3–11.

Keyes, C. L. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am. Psycho. 62, 95–108. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95

Keyes, K. M., Gary, D., O’Malley, P. M., Hamilton, A., and Schulenber, J. (2019). Recent increases in depressive symptoms among U.S. adolescents: trends from 1991 to 2018. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 54, 987–996. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01697-8

Keyes, C. L., and Waterman, M. B. (2003). “Dimensions of well-being and mental health in adulthood,” in Well-Being: Positive Development Throughout the Life Course. eds. M. Bornstein, L. Davidson, C. M. Keyes, and K. Moore (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 477–497.

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 4th Edn . New York: The Guilford Press.

Lazarus, R. (1991). Emotion and Adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lemma, P., Borraccino, A., Berchialla, P., Dalmasso, P., Charrier, L., Vieno, A., et al. (2014). Well-being in 15-year-old adolescents: a matter of relationship with school. J. Public Health 37, 573–580. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdu095

Lester, L., Waters, S., and Cross, D. (2013). The relationship between school connectedness and mental health during the transition to secondary school: A path analysis. Aust. J. Guid. Couns. 23, 157–171. doi: 10.1017/jgc.2013.20

Lim, Y. (2014). Psychometric characteristics of the Korean mental health continuum–short form in an adolescent sample. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 32, 356–364. doi: 10.1177/0734282913511431

Luijten, C. C., Kuppens, S., van de Bongardt, D., and Nieboer, A. P. (2019). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF) in Dutch adolescents. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 17:157. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1221-y

Madeu-Olivares, A., Shi, D., and Rosseel, Y. (2018). Assessing fit in structural equation models: A Monte-Carlo evaluation of RMSEA versus SRMR confidence intervals and tests of close fit. Struct. Equ. Modeling 25, 389–402. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2017.138961

Mameli, C., Biolcati, R., Passini, S., and Mancini, G. (2018). School context and subjective distress: The influence of teacher justice and school-specific well-being on adolescents’ psychological health. Sch. Psychol. Int. 39, 526–542. doi: 10.1177/0143034318794226

Marsh, H. W., Nagengast, B., and Morin, A. J. (2013). Measurement invariance of big-five factors over the life span: ESEM tests of gender, age, plasticity, maturity, and la dolce vita effects. Dev. Psychol. 49, 1194–1218. doi: 10.1037/a0026913

McKnight, C. G., Huebner, E. S., and Suldo, S. M. (2002). Relationships among stressful life events, temperament, problem behavior, and global life satisfaction in adolescents. Psychol. Sch. 39, 677–687. doi: 10.1002/pits.10062

McMillan, D. W., and Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 14, 6–23. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<6::AID-JCOP2290140103>3.0.CO;2-I

Morin, A. J., Marsh, H. W., and Nagengast, B. (2013). “Exploratory structural equation modeling,” in Quantitative Methods in Education and the Behavioral Sciences: Issues, Research, and Teaching. Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course. eds. R. Hancock and R. O. Mueller (Charlotte, US: IAP Information Age Publishing), 395–436.

Murray, C., and Greenberg, M. T. (2001). Relationships with teachers and bonds with school: social emotional adjustment correlates for children with and without disabilities. Psychol. Sch. 38, 25–41. doi: 10.1002/1520-6807(200101)38:1<25::AID-PITS4>3.0.CO;2-C

Nijs, M. M., Bun, C. J., Tempelaar, W. M., de Wit, N. J., Burger, H., Plevier, C. M., et al. (2014). Perceived school safety is strongly associated with adolescent mental health problem. Community Ment. Health J. 50, 127–134. doi: 10.1007/s10597-013-9599-1

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., and Girgus, J. S. (1994). The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychol. Bull. 115, 424–443. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424

O’Connell, M. E., Boat, T., and Warner, K. E. (2009). Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People. Progress and Possibilities. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Ornaghi, V., Pepe, A., and Grazzani, I. (2016). False-belief understanding and language ability mediate the relationship between emotion comprehension and prosocial orientation in preschoolers. Front. Psychol. 7:1534. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01534

Patel, V., Flisher, A. J., Hetrick, S., and Mcgorry, P. (2007). Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet 369, 1302–1313. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7

Patton, G. C., Coffey, C., Romaniuk, H., Mackinnon, A., Carlin, J. B., Degenhardt, L., et al. (2014). The prognosis of common mental disorders in adolescents: A 14-year prospective cohort study. Lancet 383, 1404–1411. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62116-9

Paus, T., Keshavan, M., and Giedd, J. N. (2008). Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 947–957. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513

Petrillo, G., Capone, V., Caso, D., and Keyes, C. M. (2015). The mental health continuum–short form (MHC–SF) as a measure of well-being in the Italian context. Soc. Indic. Res. 121, 291–312. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0629-3

Petrillo, G., Caso, D., and Capone, V. (2014). Un’applicazione del mental health continuum di Keyes al contesto italiano: benessere e malessere in giovani, adulti e anziani [An application of Keyes’ mental health continuum to the Italian context: well-being and illness in youth, adults and elderly]. Psicol. della Salut. 2, 159–181. doi: 10.3280/PDS2014-002010

Pianta, R. C. (1999). Enhancing Relationships Between Children and Teachers. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Pianta, R. C., and Hamre, B. K. (2009). Conceptualization, measurement and improvement of classroom processes. Educ. Res. 38, 109–119. doi: 10.3102/0013189X09332374

Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B., and Stuhlman, M. (2003). “Relationships between teachers and children,” in Comprehensive Handbook of Psychology: Educational Psychology. Vol. 7. eds. W. Reynolds and G. Miller (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley) 199–234.

Prati, G., Tomasetto, C., and Cicognani, E. (2020). Sense of community in early adolescents: Validating the scale of sense of community in early adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 41, 309–331. doi: 10.1177/0272431620912469

Pretty, G. M., Andrewes, L., and Collett, C. (1994). Exploring adolescents’ sense of community and its relationship to loneliness. J. Community Psychol. 22, 346–358. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(199410)22:4<346::AID-JCOP2290220407>3.0.CO;2-J

Proctor, C., Linley, P. A., and Maltby, J. (2009). Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. J. Happiness Stud. 10, 583–630. doi: 10.1007/s10902-008-9110-9

Reinhardt, M., Horváth, Z., Morgan, A., and Kökönyei, G. (2020). Well-being profiles in adolescence: psychometric properties and latent profile analysis of the mental health continuum model – a methodological study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18:95. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01332-0

Roorda, D., Koomen, H., Spilt, J., and Oort, F. (2011). The influence of affective teacher-student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 493–529. doi: 10.3102/0034654311421793

Samdal, O., Wold, B., and Torsheim, T. (1998). “Rationale for school: The relationship between students’ perception of school and their reported health and quality of life,” in Health Behavior in School-Aged Children: Research Protocol. ed. C. Currie (Scotland: University of Edinburgh), 51–59.

Sass, D. A., Schmitt, T. A., and Marsh, H. W. (2014). Evaluating model fit with ordered categorical data within a measurement invariance framework: A comparison of estimators. Struct. Equ. Modeling 21, 167–180. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.882658

Sawatzky, R., Ratner, P. A., Johnson, J. L., Kopec, J. A., and Zumbo, B. D. (2009). Sample heterogeneity and the measurement structure of the multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. Soc. Indic. Res. 94, 273–296. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9423-4

Sawatzky, R., Ratner, P. A., Johnson, J. L., Kopec, J. A., and Zumbo, B. D. (2010). Self-reported physical and mental health status and quality of life in adolescents: a latent variable mediation model. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 8:17. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-17

Seligman, M. E., and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 55, 5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Stark, L. J., Spirito, A., Williams, C. A., and Guevremont, D. C. (1989). Common problems and coping strategies I: Findings with normal adolescents. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 17, 203–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00913794

Suldo, S. M., Friedrich, A. A., White, T., Farmer, J., Minch, D., and Michalowski, J. (2009). Teacher support and adolescents’ subjective well-being: A mixed-methods investigation. School Psych. Rev. 38, 67–85. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2009.12087850

Suldo, S. M., Gormley, M. J., DuPaul, G. J., and Anderson-Butcher, D. (2014). The impact of school mental health on student and shool-level academic outcomes: current status of the research and future directions. School Ment. Health 6, 84–98. doi: 10.1007/s12310-013-9116-2

Suldo, S. M., and Huebner, E. S. (2004). Does life satisfaction moderate the effects of stressful life events on psychopathological behavior during adolescence? Sch. Psychol. Q. 19, 93–105. doi: 10.1521/scpq.19.2.93.33313

Terjesen, M. D., Jacofsky, M., Froh, J., and DiGiuseppe, R. (2004). Integrating positive psychology into schools: Implications for practice. Psychol. Sch. 41, 163–172. doi: 10.1002/pits.10148

Thakkar, J. J. (2020). Structural Equation Modelling. Application for Research and Practice (with AMOS and R). Singapore: Springer.

Tonci, E., De Domini, P., and Tomada, G. (2012). La misura della relazione alunno-insegnante: adattamento dello student-teacher relationship questionnaire secondo una prospettiva integrata [The measure of the pupil-teacher relationship: adaptation of the student-teacher relationship questionnaire] G . Ital. di Psicol. 39, 667–693. doi: 10.1421/38777

Torsheim, T., and Wold, B. (2001). School-related stress, support, and subjective health complaints among early adolescents: a multilevel approach. J. Adolesc. 24, 701–713. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0440

Twenge, J. M. (2020). Why increases in adolescent depression may be linked to the technological environment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 32, 89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.036

Twenge, J., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., and Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among u.s. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 6, 3–17. doi: 10.1177/2167702617723376

Valdez, C. R., Lambert, S. F., and Ialongo, N. S. (2011). Identifying patterns of early risk for mental health and academic problems in adolescence: A longitudinal study of urban youth. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 42, 521–538. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0230-9

van der Ende, J., and Verhulst, F. C. (2005). Informant, gender and age differences in ratings of adolescent problem behaviour. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 14, 117–126. doi: 10.1007/s00787-005-0438-y

Veronese, G., Pepe, A., Alzaanin, W., and Shoman, H. (2020). Sources of functioning, symptoms of trauma, and psychological distress: A cross-sectional study with Palestinian health workers operating in West Bank and Gaza strip. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 90, 751–759. doi: 10.1037/ort0000508

Vieno, A., Perkins, D. D., Smith, T. M., and Santinello, M. (2005). Democratic school climate and sense of community in school: A multilevel analysis. Am. J. Community Psychol. 36, 327–341. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8629-8

Wang, M., Brinkworth, M., and Eccles, J. (2013). Moderating effects of teacher-student relationship in adolescent trajectories of emotional and behavioral adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 49, 690–705. doi: 10.1037/a0027916

Weare, K., and Nind, M. (2011). Mental health promotion and problem prevention in schools: what does the evidence say? Health Promot. Int. 26, i29–i69. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dar075

World Health Organization (2005). Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice. Geneva, Switzerland: Publications of the World Health Organization.

World Health Organization (2012). Risks to mental health: An overview of vulnerabilities and risk factors background paper by who secretariat for the development of a comprehensive mental health action plan . Available at: https://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/risks_to_mental_health_EN_27_08_12.pdf (Accessed April 23, 2021).

Yeo, L. S., Ang, R. P., Chong, W. H., and Huan, V. S. (2007). Gender differences in adolescent concerns and emotional well-being: perceptions of Singaporean adolescent students. J. Genet. Psychol. 168, 63–80. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.168.1.63-80

Zappulla, C., Pace, U., Lo Cascio, V., Guzzo, G., and Huebner, E. S. (2014). Factor structure and convergent validity of the long and abbreviated versions of the multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale in an Italian sample. Soc. Indic. Res. 118, 57–69. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0418-4

Zullig, K. J., Valois, R. F., Huebner, E. S., and Drane, J. W. (2001). Relationship between perceived life satisfaction and adolescents’ substance abuse. J. Adolesc. Health 29, 279–288. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00269-5

Keywords: school mental health, adolescence, life satisfaction, teacher-student relationship, school connectedness, structural equation modelling

Citation: Cavioni V, Grazzani I, Ornaghi V, Agliati A and Pepe A (2021) Adolescents’ Mental Health at School: The Mediating Role of Life Satisfaction. Front. Psychol . 12:720628. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.720628

Received: 07 June 2021; Accepted: 13 July 2021; Published: 18 August 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Cavioni, Grazzani, Ornaghi, Agliati and Pepe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Valeria Cavioni, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on University Students' Mental Health: A Literature Review

Beatta zarowski, demetrios giokaris.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Olga Green [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2024 Feb 11; Collection date 2024 Feb.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 4.0., which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This review aims to focus on the effects of COVID-19 on university students' mental health and deepen our understanding of it. The conclusions are based on the review of 32 studies conducted during the pandemic. This review confirms that university students were at high risk for mental health disorders, heightened stress, and increased sleep comorbidities both pre-pandemic and during the pandemic. This literature review confirmed a few universal trends, i.e., increased stress, anxiety, and depression, during the pandemic. The rates of insomnia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and suicidal ideation also went up. Overall, female students are at a disadvantage in the development of mental health issues. Male students coped better but may be at higher risk for lethality in suicidal ideation. Students with a history of mental health issues and other comorbidities prior to the pandemic had worse outcomes compared to healthy individuals. The study points to a strong positive correlation between fear and increased rates of stress, anxiety, and insomnia. There is also a positive correlation between declining mental health and online learning. A strong negative correlation was present between physical activity and depressive symptoms. These findings are universal across many countries and regions where the studies occurred.

Keywords: suicidal ideation, depression, anxiety, stress, students, mental health, covid-19

Introduction and background

The COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020 and profoundly impacted university students' mental, emotional, academic, social, and other aspects of life. Mid-pandemic studies [ 1 - 5 ] and pre-pandemic publications, including 2017 WHO mental health estimates, place university students at high risk for mental health dysfunction, with a higher prevalence of psychiatric morbidity compared to the general global population, with 4.4% for anxiety and 3.6% for depression [ 5 ]. Unexpected and sudden restrictions, isolation policies, and lockdowns in many countries were meant to protect communities and society at large but had a lot of unintended negative consequences. This review aims to present evidence of the disruptive trends uniquely amplified globally within the university student population and identified in the literature published in 2020-2023 on this topic. The review will analyze 32 peer-reviewed sources focusing on the pandemic's mental, psychological, academic, social, and other effects on university students.

Methodology

This literature review utilized several scientific literature databases, including Science Direct, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and PubMed, to identify articles that include the search criteria, such as those related to the prevalence of anxiety, stress, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), sleep disorders, and suicidal ideation and other symptoms in students in university settings. For cross-reference, the review includes topics identified in scientific literature across different geographical regions and comprises the most prevalent mental health issues. The sources originated from different countries, including the United States, Denmark, UK, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, UAE, Italy, Jordan, India, Lebanon, Egypt, Germany, Bangladesh, Iraq, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, and China, offering an international viewpoint on the mental health impact of the pandemic on university students. Each article was published following a scientific peer-review process, ensuring the reliability and validity of the data presented.

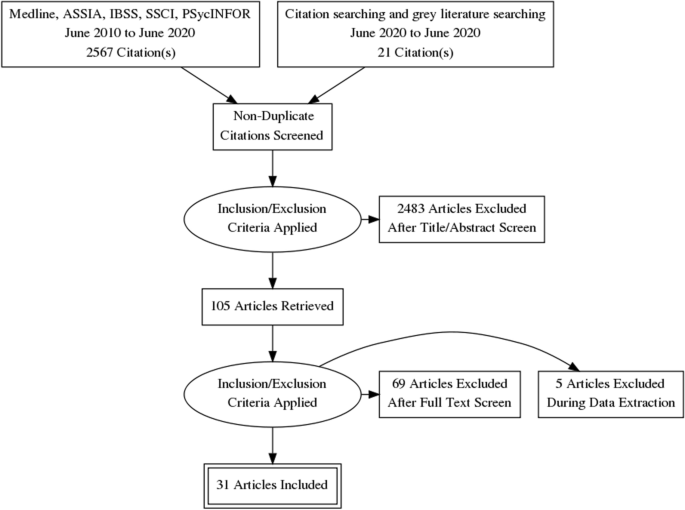

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were put together to preserve focus and relevance. The review included only peer-reviewed literature published between January 2020 and December 2023. The timeframe included research completed during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Only the publications written in English were studied for inclusion. Studies on the mental health issues and consequences of the COVID-19 epidemic on university students were included, while studies on other populations or unrelated issues were discarded. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study.

Stress and anxiety

The WHO estimates that the most prevalent mental health disorder is anxiety, affecting up to 1/3 of adults in their lifetime [ 4 ]. Following the implementation of quarantines, lockdowns, and suspension of face-to-face teaching, universities and colleges switched to online remote learning modes. This sudden change altered students' functioning, primarily evidenced by increased stress and anxiety. The review demonstrated several trends directly resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, such as fear of contamination, a rise in OCD, a decline in personal interactions, and long hours pursuing online learning. The review also identified several indirect stressors caused by COVID-19: financial hardships, decreased sleep quality, rise in pre-existing anxiety, depression, and stress. According to pre-pandemic data, direct and indirect stressors have contributed significantly to an overall spike in stress and anxiety. Female gender emerged as an additional factor for increased symptoms and comorbidities during COVID-19.

The most apparent stressor was the danger of contamination [ 3 , 6 - 10 ]. In the first few months of the pandemic, the university academic population in Turkey cited danger and fear of infection as the most significant stressors affecting their day-to-day lives [ 3 ]. American students echoed the same fear of infection among their family members and themselves [ 10 ]. Researchers concluded that prolonged exposure to fear positively correlated with increased anxiety [ 6 ]. The announcements of the pandemic often came with the government's policies of mandatory lockdowns to reduce the spread of COVID-19 infections. The restrictions considerably changed lifestyles and social relationships. For the first time in their lives, students experienced home quarantine. The research on increased stress and the adverse effects of at-home isolation was conducted during other pandemics and during COVID-19 [ 2 , 11 ]. The magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic multiplied stress and other adverse effects and eliminated most of the social person-to-person interaction [ 2 , 12 , 13 ]. Researchers consistently show the harmful effects of social distancing and decreased social interactions during COVID-19 closures [ 10 ]. All those elements contributed to psychological dysfunction, increased stress, anxiety symptoms [ 14 ], and changes in sleeping patterns [ 15 , 16 ]. Other studies show a link between COVID-19-induced home isolation and changed sleep patterns [ 2 ], COVID-19 and stress, and poor academic performance [ 2 , 17 ].

Following announcements of public restrictions, colleges and universities rushed to implement online-only learning models [ 2 , 7 - 9 , 18 , 19 ]. Preventing academic loss and adopting digital learning allowed students to continue their education under home quarantine. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Brooks et al. [ 11 ] analyzed the effects of home quarantine during other outbreaks. Brooks et al. hypothesize that education, when conducted under home quarantine, is a cause of increased frustration, stress, anger, and anxiety. The dominance of technology-driven college education associated with long online hours and possible internet addiction leads to a significant increase in anxiety levels [ 20 ]. The shift from in-person to digital education among university students contributed to increased anxiety prevalence [ 18 , 20 ]. A positive correlation between declining mental health and online learning was noted among Asian students, as observed by Islam et al. [ 21 ]. The constant fear, online presence, the enormous volume of information consumed, endless searches, and associated behaviors amplified anxiety and stress [ 8 , 22 ] and were a reason for the rise in anxiety [ 6 ] and were labeled as "cyberchondria" [ 7 ].

As the closures and lockdowns continued, students suffered financial hardships, causing anxiety [ 7 , 8 , 22 , 23 ]. College students reported adverse events such as declining family income, food and housing insecurity, and inadequate financial resources [ 23 ] to afford food, housing, and technology for effective learning. These indirect stressors disrupted the lives of low-income students more significantly and caused higher rates of stress and anxiety than those of high-income students [ 23 ]. Pandemic-generated unemployment caused working students to exhibit additional anxiety. Asian students were also reporting rising anxiety levels during the pandemic, particularly those who did not have access to resources [ 21 ], such as reliable internet, inability to purchase subscriptions, technology, or supplies, and who suffered from economic instability.

The long-term effects of the pandemic-related students' stress did not end with the first vaccination. This elevated stress trend continued for months after the initial impact [ 8 , 24 - 26 ], and even as of April 2021, 71% of Asian students were still reporting mild anxiety symptoms [ 26 ]. This finding contrasts with pre-pandemic anxiety levels recorded at about 15.7% and rising to 18.86% in March 2020 and to 32.68% in September 2020, respectively [ 26 ]. Al-Kumaim et al. [ 24 ] indicated that the pandemic had a considerable influence on students' psychological well-being, with anxiety being one of the most reported symptoms. The length of the pandemic hurt the mental health of university students. Students' anxiety levels continued at elevated levels. This observation is congruent with increased anxiety (60.8%) for students surveyed in 2021 [ 27 ]. The length of the pandemic was also detrimental to the deterioration of the mental health of the students.

Studies consistently found that female students were more at risk for increased anxiety during the pandemic. The research does not firmly establish why the female gender appears at significant risk for developing anxiety and increased stress [ 8 , 9 , 14 - 16 , 18 , 20 , 28 - 32 ]. This female factor could be due to the multifaceted nature of biological, psychosocial, cultural, and behavioral differences before and during the pandemic [ 29 ]. The exact calculations on how wide the gap is between male and female students' stress levels during the pandemic vary from paper to paper. The levels of pre-pandemic anxiety in female vs. male students were established in a Chinese longitudinal study showing anxiety for female students at 22%, while male students scored at 19% [ 29 ]. The study of students in Turkey [ 3 ] mid-COVID-19 demonstrates that the trend continues at almost twice the rate of anxiety, with 63% in females vs. 36% in male students. A systemic review by Liyanage et al. [ 4 ] quotes global differences in stress and anxiety for university students with mid-pandemic symptoms at 43% for females and 39% for males.

Several scholarly papers discuss the presence of a few well-established protective factors that reduce the levels of stress and anxiety experienced by students during the pandemic. The researchers zeroed in on the male gender [ 9 , 29 - 31 , 33 ], the presence of physical health [ 31 ], participation in exercise [ 34 ], student seniority, and urban residence [ 12 ]. Pre and mid-pandemic literature suggests that male students have shown consistently lower stress and anxiety symptoms than their female counterparts. This review shows strong mid-pandemic consistency for gender differences across many authors [ 3 , 6 - 9 , 13 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 32 ]. The articles reviewed do not explain why the male gender appears less affected by mental health challenges during the pandemic.

Academic stress is a part of a typical student learning cycle. Students who had senior student status experienced less stress [ 16 , 28 , 32 ]. Wang et al. [ 33 ] confirmed that increased stress and anxiety are more prevalent in junior student populations. The differences between the junior and senior students can be explained by older age, more independence, and autonomy contributing to frustrations. Undergraduate students need time to develop psychological and emotional skills to handle stress better [ 33 ].