13 Romantic Period: Opera

Learning objectives.

- Explain how Giuseppe Verdi’s Romantic Period operatic style reflects the Italian bel canto tradition.

- Explain how Romantic Period opera differs from Classical Period opera in the distinctions between recitative and aria and the use of the orchestra.

- Analyze Verdi’s melodic gift and his combination of comedy and tragedy in scenes from Act III of Rigoletto .

- Compare and contrast the operatic styles of Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner.

- Explain how Richard Wagner’s music dramas reflect Wagner’s background in symphonic music, particularly the symphonies of Beethoven.

- Explain the concept of a Leitmotiv and identify their use in the final scene from The Valkyrie .

- Explain how Leitmotivs influenced the development of film music.

Francis Scully

Romantic Opera

Given Romantic composers’ interest in connecting to other arts (literature, visual art), opera is obviously going to be a big deal in the nineteenth century. Like all art and music in the Romantic era, opera is going to get more “serious.” It’s no longer simply a vehicle for spectacle and entertainment.

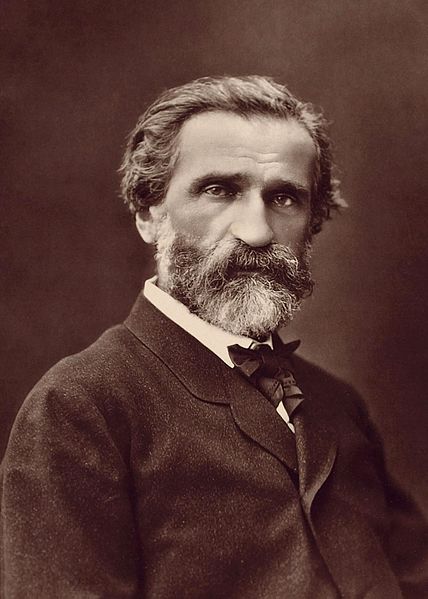

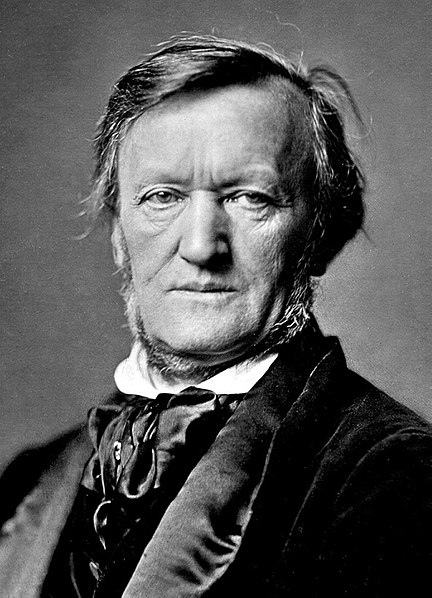

There are many great opera composers and operas in the Romantic Period, but two names tower above them all: the Italian opera composer Giuseppe Verdi and the German opera composer Richard Wagner.

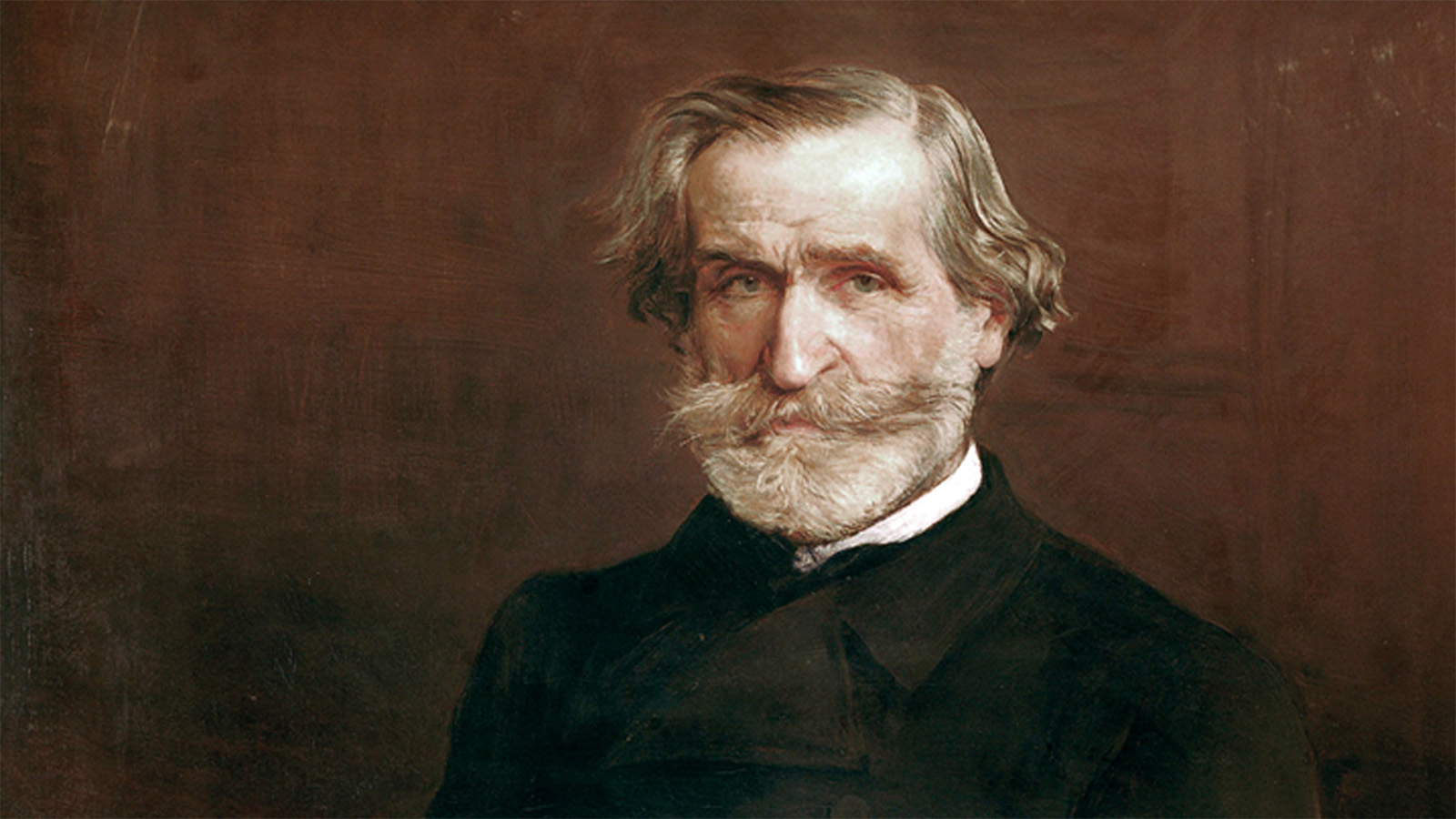

Verdi, Giuseppe (1813-1901)

Verdi is considered the greatest of Italian opera composers. He studied music in Milan, home of the famous La Scala Opera House (still one of the major opera houses of the world), and he composed opera almost exclusively in his career. He had his first big success with Nabucco (1842), and in the 1850s, he brought out his trio of “smash hits” Rigoletto (1851), Il Trovatore (1853), and La Traviata (1853). Verdi was politically involved as a supporter of the Italian liberation movement. In his seventies, he wrote two of his greatest works, both based on Shakespeare: Falstaff and Otello . Other important works include Aida (1871) and a brilliant and dramatic Requiem Mass.

Verdi inherits a style of early nineteenth-century Italian opera known as “ bel canto ,” which literally means “beautiful singing.” For the bel canto composers like Rossini, Bellini, and Donizetti, music was intended to showcase the beauty of the human voice. Verdi is similarly praised for his ability to foreground spectacular feats of virtuoso singing, and he is celebrated for his astonishing gift for writing memorable melodies. Verdi wrote some of the most beloved arias in the operatic repertoire, and they are often extracted for concert performances. Watch this aria (“La donna è mobile”) from Verdi’s opera Rigoletto and you’ll instantly recognize Verdi’s melodic gift:

Video 13.1: Rigoletto La Dona e mobile, performed by Luciano Pavarotti

Like his bel canto compatriots, Verdi values the beauty of the human voice as the basis of opera, and he writes a lot of gorgeous melodies that highlight this, but Verdi does not allow this emphasis on singers to overshadow his real interest, which is drama , placing vivid characters in extreme situations and ratcheting up the tension.

Dramatic Fluidity

If you recall from previous discussion of opera and the scenes in Mozart’s The Marriage of F igaro , there was a clear distinction between the recitative and the aria (or ensemble ). The recitative almost always had a simple harpsichord accompaniment and was musically less interesting. The arias and ensembles provided the musical interest. In a certain sense, the piece essentially switched back and forth between drama (recitative) and music (aria/ensemble). In the Romantic Period, however, composers were interested in creating a more fluid and unified opera, one in which the music works hand-in-hand with the drama continuously.

To do this, Romantic Period composers get rid of the harpsichord (the simple keyboard accompaniment, playing rolled chords underneath recitative) altogether. Instead, they use the orchestra throughout the whole opera. Of course, they still need some kind of recitative-like sections in order to clearly present plot action and dialogue, but now the orchestra plays more active, motivic, and dramatic music as opposed to the simple chords of 18 th -century recitative. Notice in the two Romantic Period operas that we will watch that the distinction between aria and recitative is increasingly blurred.

Rigoletto (1851)

To get a sense of how Verdi unifies spectacular singing, memorable melodies, and intense drama, we will watch two scenes from Verdi’s 1851 opera Rigoletto .

Rigoletto was based on a play called “Le Roi s’amuse” (The King Amuses Himself) by the French Romantic writer Victor Hugo, who is best known for his novels The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1833) and Les Miserables (1862). The opera is set in the Italian city of Mantua during the 1500s, where the title character, Rigoletto, serves as the hunchbacked court jester to womanizing lothario, Duke of Mantua. In the aria that we heard above (“La donna è mobile”), the Duke of Mantua presents his womanizing philosophy of life (to paraphrase, something like “women…you can’t live with them, you can’t live without them, might as well have some fun with them”). Rigoletto typically mocks the various men whose wives and girlfriends fall for the Duke, and in the opera’s first scene, Count Monterone, one of the Duke’s victims who has been mercilessly taunted by Rigoletto, pronounces a curse on Rigoletto. Later in the opera, Rigoletto learns, much to his horror, that his precious young daughter Gilda has also been seduced by the Duke.

In the opera’s final act (Act III), Rigoletto plots his revenge against his employer by hiring the assassin Sparafucile to kill the Duke. But first, Rigoletto wants his daughter to see the Duke in the act of cheating on her. Rigoletto and Gilda perch outside of an inn where Sparafucile’s sister Maddalena has lured the Duke to set up the assassination. The Duke and Maddalena flirt with each other while Rigoletto and Gilda watch in horror. In this masterful ensemble, we hear the emotions of the four different characters at the same time . Verdi accomplishes this by using different rhythms, different melodic shapes, and different pitch ranges for each of the voices (Gilda = soprano, Maddalena = alto, Duke = tenor, Rigoletto = bass). What’s more, in this incisive scene, Verdi deftly combines tragedy (the anger and despair experienced by Rigoletto and Gilda) with comedy (the flirting and playfulness of Maddalena and the Duke’s exchange). We will start the scene with the Duke’s aria and observe again how the different sections of Romantic opera unfold more seamlessly than in Classical Period opera.

Video 13.2: Rigoletto , Verdi, Watch from 1:29:00 to 1:37:03

https://youtube.com/watch?v=4zlZ5QpotC4

Listening Guide: Rigoletto from 1:29:00 to 1:37:03

| Time | Description |

|---|---|

| 1:29:00–1:31:39 | The Duke sings his trademark aria “La donna è mobile.” |

| 1:31:40–1:33:07 | Transitional section where the Duke woos Maddalena while Rigoletto and Gilda look on. |

| 1:33:08–1:37:03 | “Bella figlia dell’amore”: The quartet in which each character presents conflicting emotions. |

Following this scene, the Duke goes to sleep in the inn, where he sings another verse of “La donna è mobile” as he dozes off (Verdi is also cleverly reminding the audience of his “hit tune”). Maddalena, who has now fallen under the Duke’s spell, feels sympathy for him and pleads with her brother to spare his life. But Sparafucile is an honorable businessman and only agrees to spare the Duke if someone arrives at the inn before dawn, when Rigoletto agrees to return for the body. Gilda, who has snuck away from her father, overhears the exchange, and in the middle of a raging storm, knocks on the door, willing to sacrifice her life to save the Duke. In the morning, Rigoletto returns to the inn to pay Sparafucile the rest of his fee and gloat over the dead body of the Duke. Little does he know, the body that he’s collecting from Sparafucile is that of his own daughter! Rigoletto plans to take the body to dump in the river when he overhears the Duke waking up and singing (yet again) his signature tune. The playful melody delivers the shock to Rigoletto that the body in the body bag is not that of his nemesis. He opens it up to discover his daughter. This being opera, Gilda is just conscious enough to sing an impassioned duet as father and daughter say goodbye to each other and Gilda expires.

Video 13.3: Now watch from 1:47:30 to 1:58:28

Listening Guide: Rigoletto from 1:47:20 to 1:58:28

| Time | Description |

|---|---|

| 1:47:20–1:48:59 | Rigoletto prepares to meet Sparafucile. |

| 1:49:00–1:50:57 | Rigoletto receives the body from Sparafucile and he begins to celebrate. |

| 1:50:58–1:55:14 | The Duke sings “La donna è mobile” and Rigoletto realizes that his daughter is in the body bag. Gilda explains how she came to be Sparafucile’s victim. |

| 1:55:15–1:58:28 | Rigoletto and Gilda sing a tender duet as Gilda dies. Rigoletto realizes that Count Monterone’s curse has been fulfilled. |

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Adapted from “Music of Richard Wagner,” Understanding Music By Alan Clark, Thomas Heflin, Jeffrey Kluball, & Elizabeth Kramer Revised by Jonathan Kulp Adapted by Francis Scully

If Verdi continued the long tradition of Italian opera, Richard Wagner provided a new path for German opera. Wagner (1813-1883) may well have been the most influential European composer of the second half of the nineteenth century. Never shy about self-promotion, Wagner himself clearly thought so. Wagner’s influence was both musical and literary. His dissonant and chromatic harmonic experiments even influenced the French, whose music belies their many verbal denouncements of Wagner and his music. His essays about music and autobiographical accounts of his musical experiences were widely followed by nineteenth-century individuals, from the average bourgeois music enthusiast to philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche. Most disturbingly, Wagner was rabidly anti-Semitic, and generations later, his writing and music provided propaganda for the Nazi Third Reich.

Born in Leipzig, Germany, Wagner initially wanted to be a playwright like Goethe, until as a teenager he heard the music of Beethoven and decided to become a composer instead. He was particularly taken by Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and the addition of voices as performing forces into the symphony, a type of composition traditionally written for orchestra. Seeing in this work an acknowledgment of the powers of vocal music, Wagner set about becoming an opera composer. Coming of age during a time of rising nationalism, Wagner criticized Italian opera as consisting of cheap melodies and insipid orchestration unconnected to its dramatic purposes, and he set about providing a German alternative. He called his operas “music dramas” in order to emphasize a unity of text, music, and action and declared that they would be Gesamtkunstwerk , or “total works of art.” As part of his program, he wrote his own librettos and aimed for what he called unending melody: the idea was for a constant lyricism, carried as much by the orchestra as by the singers.

Perhaps most importantly, Wagner developed a system of what scholars have come to call Leitmotivs. Leitmotivs , or “guiding motives,” are musical motives that are associated with a specific character, theme, or locale in a drama. Wagner integrated these musical motives in the vocal lines and orchestration of his music dramas at many points. Wagner believed in the flexibility of such motives to reinforce an overall sense of unity within his compositions, even if primarily at a subconscious level. Thus, while a character might be singing a melody line using one leitmotiv, the orchestration might incorporate a different leitmotiv, suggesting a connection between the referenced entities. The use of leitmotivs also reflects Wagner’s understanding of opera as a symbolic artform rather than a “realistic” form of drama. To that end, his mature operas are all based on either medieval legends ( Tannhäuser [1845], Tristan und Isolde [1859], Parsifal [1882]) or Germanic mythology ( The Ring of the Nibelungs [1876]).

Wagner also designed and built a theater for the performance of his own music dramas. The Festival Theatre in Bayreuth, Germany, was the first to use a sunken orchestra pit, and its huge backstage area allowed for some of the most elaborate sets of Wagner’s day. It was here that his famous cycle of music dramas, The Ring of the Nibelungen , was performed, starting in 1876. The Ring of the Nibelungen consists of four music dramas with over fifteen hours of music. Wagner took the story from a Nordic mythological legend that stems back to the Middle Ages. In it, a piece of gold is stolen from the Rhine River and fashioned into a ring, which gives its bearer ultimate power. The cursed ring changes hands, causing destruction around whoever possesses it. Eventually the ring is returned to the Rhine River, thereby closing the cycle. Into that story, which some may recognize from the much later fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings , Wagner interwove stories of the Norse gods and men. Wagner’s four music dramas trace the saga of the king of the gods, Wotan, as he builds Valhalla, the home of the gods, and attempts to order the lives of his children, including that of his daughter, the Valkyrie warrior Brünnhilde.

Focus Composition: Conclusion to The Valkyrie (1876)

In the excerpt we’ll watch from the end of The Valkyrie , the second of the four music dramas, Brünnhilde has gone against her father, and because Wotan cannot bring himself to kill her, he puts her to sleep before encircling her with flames, a fiery ring that both imprisons and protects his daughter. This excerpt provides several examples of the Leitmotivs for which Wagner is so famous. Their presence, often subtle, is designed to guide the audience through the drama. They include melodies, harmonies, and textures that represent Wotan’s spear, the god Loge—a shape-shifting life force that here takes the form of fire—sleep, the magic sword, and fate. The sounds of these motives are discussed briefly below and accompanied by excerpts from the musical score for those of you who can read musical notation.

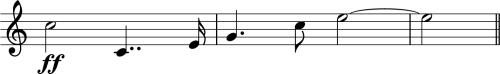

The first motive heard in the video you will watch is Wotan’s Spear . The spear represents Wotan’s power. In this scene, Wotan is pointing it toward his daughter Brünnhilde, ready to conjure the ring of fire that will both imprison and protect her. Representing a symbol of power, the spear motive is played here at a forte dynamic on piano. Here it descends in a minor scale that reinforces the seriousness of Wotan’s actions.

Audio ex. 13.1: Wotan’s Spear, from The Valkyries , Richard Wagner, composer

Wotan commands Loge to appear, and suddenly the music breaks out in a completely different style. Loge’s music —sometimes also referred to as the magic fire music—is in a major key and appears in upper woodwinds such as the flutes. Its notes move quickly with staccato articulations suggesting Loge’s free spirit and shifting shapes.

Depicting Brünnhilde’s descent into sleep, Wagner wrote a chromatic musical line that starts high and slowly moves downward. We call this phrase the Sleep motive:

Audio ex. 13.2: Brünnhilde’s sleep motive from The Valkyries , Richard Wagner, composer

https://louis.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/4/2022/05/6-24sleep.mp3

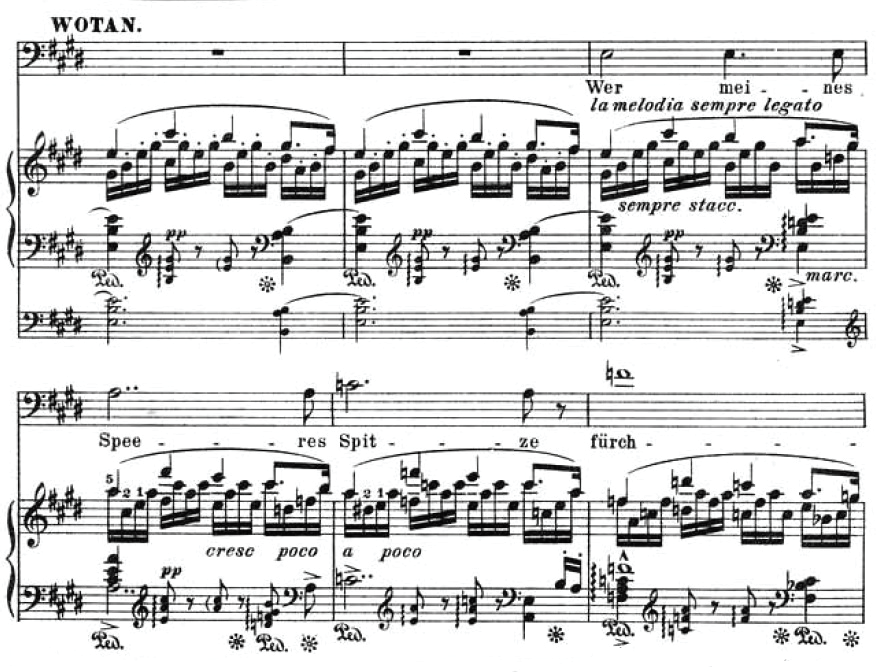

After casting his spell, Wotan warns anyone who is listening that whoever would dare to trespass the ring of fire will have to face his spear. As the drama unfolds in the next opera of the tetralogy, one character will do just that: Siegfried, Wotan’s own grandson. He will release Brünnhilde using a magic sword. The melody to which Wotan sings his warning with its wide leaps and overall disjunct motion sounds a little bit like the motive representing Siegfried’s sword.

Audio ex. 13.3: “Siegfried’s Sword” from The Valkyries , Richard Wagner, composer

https://louis.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/4/2022/05/sword.mp3

One final motive is prominent at the end of The Valkyrie , a motive which is referred to as Fate. It appears in the horns and features three notes: a sustained pitch that slips down just one step and then rises the small interval of a minor third to another sustained pitch.

Now that you’ve been introduced to all of the leitmotivs in the excerpt, follow along with the listening guide. As you listen, notice how prominent the huge orchestra is throughout the scene, how it provides the melodies, and how the strong and large voice of the bass-baritone singing Wotan soars over the top of the orchestra (Wagner’s music required larger voices than earlier opera as well as new singing techniques). See if you can hear the Leitmotivs , there to absorb you in the drama. Remember that this is just one short scene from the midpoint of the approximately fifteen-hour-long tetralogy.

Video 13.4: Wotan’s Farewell, performed by Sir John Tomlinson

Listening Guide

- Composer: Richard Wagner

- Composition: The Valkyries , Final Scene: Wotan’s Farewell

- Genre: Music drama (or nineteenth-century German opera)

- Form: Through-composed, using Leitmotivs

- Nature of text:

Loge, hear! List to my word! As I found thee of old, a glimmering flame, as from me thou didst vanish, in wandering fire; as once I stayed thee, stir I thee now! Appear! come, waving fire, and wind thee in flames round the fell!

(During the following he strikes the rock thrice with his spear.)

Loge! Loge! appear! He who my spearpoint’s sharpness feareth shall cross not the flaming fire!

- Performing forces: Bass-baritone Wotan, large orchestra

- It uses Leitmotivs.

- The orchestra provides an “unending melody” over which the characters sing.

- Listen for the specific Leitmotivs.

Listening Guide: The Valkyries, Wotan’s Farewell

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Leitmotiv and Form |

|---|---|---|

| 0:00 | Descending melodic line played in octaves by the lower brass | Wotan’s spear: Just the orchestra |

| 0:08 | Wotan sings a motivic phrase that ascends; the orchestra ascends, too, supporting his melodic line | Löge, hör! Lausche hieher! Wie zuerst ich dich fand, als feurige Glut, wie dann einst du mir schwandest, als schweifende Lohe; wie ich dich band |

| 0:28 | Appears as Wotan transitions to new words still in the lower brass | Spear again: Bann ich dich heut’! |

| 0:29 | Trills in the strings and a rising chromatic scale introduce Wotan’s striking of his spear and producing fire introducing the . . . | Fire music: Herauf, wabernde Loge, umlodre mir feurig den Fels! Loge! Loge! Hieher! |

| 0:58 | fire music played by the upper woodwinds (flutes, oboes, and clarinets). | Fire music: Just the orchestra |

| 1:41 | Slower, descending chromatic scale in the winds represents Brünnhilde’s descent into sleep | Sleep: Just the orchestra |

| 2:06 | As Wotan sings again, his melodic line seems to allude to the sword motive, doubled by the horns and supported by a full orchestra. | Sword motive: Wer meines Speeres Spitze fürchtet, durchschreite das Feuer nie! |

| 2:40 | Lower brass prominently plays the sword motive while the strings and upper woodwinds play motives from the fire music; a gradual decrescendo | Sword motive; fire music continues: Just the orchestra |

| 4:05 | The horns and trombones play the narrow-raged fate melody as the curtain closes | Fate motive: Just the orchestra |

Something to Think About

Compare and contrast the operatic styles of Verdi (in Rigoletto ) and Richard Wagner (in his opera The Valkyrie ). Consider how the two composers use the voice, how they use the orchestra, and the subject matter. Which approach do you find more effective? Entertaining? Dramatically satisfying? Musically satisfying?

Leitmotifs in Lord of the Rings

Wagner’s Leitmotif technique was one of the most influential techniques to come out of the 19th century. Hollywood composers have been using it for many years to represent things like giant sharks in Jaws (John Williams, 1976), forces of evil in Star Wars , and many other ideas, characters, and objects in other films. You might find it interesting to watch this video about the Leitmotifs that are at work in the score for The Lord of the Rings .

Chapter Summary

In this chapter, we looked at the music of two of the giants of Romantic Period opera, the Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi and the German composer Richard Wagner. Verdi hailed from the bel canto Italian tradition, which put the human voice at the center of the operatic spectacle. But Verdi never let his beautiful melodies hamper the passionate intensity of the drama. While Wagner’s operas are no less dependent on superhuman singing abilities, Wagner transformed the role of the orchestra in his works. Through the presentation and development of leitmotivs , the orchestra becomes an essential character in the drama, providing psychological commentary on the stage action, as well as propelling the action forward. Wagner returned to myths and legends for the literary material for his operas to create more of a symbolic artwork. While Wagner lived many years before the development of motion pictures, his Leitmotiv technique became an essential component of musical storytelling in film.

Test Your Understanding

Music Appreciation Copyright © 2022 by LOUIS: The Louisiana Library Network is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Portrait of a Woman, Said to be Madame Charles Simon Favart (Marie Justine Benoîte Duronceray, 1727–1772)

François Hubert Drouais

The Ballet from "Robert le Diable"

Edgar Degas

Louis Gueymard (1822–1880) as Robert le Diable

Gustave Courbet

Bacchante with lowered eyes

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Marcantonio Pasqualini (1614–1691) Crowned by Apollo

Andrea Sacchi

Head of Jean-Baptiste Faure (1830–1914)

Edouard Manet

Jean Sorabella Independent Scholar

October 2004

Opera, whose name comes from the Italian word for a work, realizes the Baroque ambition of integrating all the arts. Music and drama are the fundamental ingredients, as are the arts of staging and costume design; opera is therefore a visual as well as an audible art. Throughout its history, opera has reflected trends current in the several arts of which it is composed. Developments in architecture and painting have manifested themselves on the operatic stage in the design of sets and costumes for specific performances, and opera has also affected the visual arts beyond the stage in such domains as the design and decoration of opera houses and the portraiture of singers and composers. A feature unique to opera, however, is the power of music, particularly that written for the several registers of the human singing voice, which is arguably the artistic means best suited to the expression of emotion and the portrayal of character.

From the Court to the Public Theater In its origins, opera, like every other type of spectacle, expressed noble prerogatives and was staged in courtly settings. In seventeenth-century Italy, the birthplace of the form, lavish entertainments featuring fireworks and sensational effects as well as instrumental music, singing, dances, and speeches were staged to celebrate princely weddings or to welcome regal guests. Although not operas in the modern sense, these integrated entertainments fostered collaboration among the arts and prompted the theoretical justifications upon which true opera—and ballet , whose early development runs parallel—was built. The Florentine Camerata, a group of composers and dramatists active in Florence around 1600, set out to revive the great traditions of the classical Greek stage , in which music and drama reinforced each other. Toward this end, they developed recitative, a type of sung speech featuring the solo voice and an unadorned vocal line expressive of the text. Early operas, largely based on mythological themes and peopled with noble characters, promoted aristocratic ideals.

Although music and drama were the essential features of opera, visual effects often dominated the court productions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and the designers of sets and theatrical machinery sometimes received greater acclaim than the composers who wrote the music. The audiences for court performances were part of the spectacle, since the convention of darkening the theater did not yet exist. Magnificently garbed and seated in orderly ranks, the spectators followed the action of the opera, which might last several hours, in a printed libretto, literally “a little book” produced for the occasion. Today the word libretto denotes the text of the opera, the drama that is set to music, but in the days of court opera, librettos were attractively illustrated and therefore involved the talents of draftsmen and engravers , who were also engaged to commemorate the festivities.

Although the spectacular emphasis of court performances continued as opera evolved, musical considerations guided its evolution. It was early noticed that music could express mood, define character, and enliven dramatic situations, sometimes more eloquently than verbal expression alone. Arias for solo voice might express a sentiment both musically and verbally; ensembles, choruses, and orchestral interludes likewise produced effective color. Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), who used recitative as well as lyrical solos, madrigals, and instrumental color in operas on a variety of classical themes, is considered the first genius of operatic composition, and his “favola in musica” Orfeo (1607) is often seen as the first true opera. Although Monteverdi spent the early part of his career writing for the dukes of Mantua, his last works were intended for the public opera houses of Venice, the first of which opened in 1637. The public became and still remains the primary audience for the opera, although court productions continued to be devised wherever courts existed.

Opera in the Age of Enlightenment By the end of the eighteenth century, opera was an international phenomenon, and both comic and serious genres flourished in France, England, and the Habsburg empire as well as in Italy, although Italian remained the standard language of the libretto. Decorative objects of the period suggest the popularity of opera outside a court context ( 17.190.1867 ). Painters, such as François Boucher and Antoine Watteau , continued to devise set designs, but focus shifted to the quality of the music, which rose very high. Under composers such as Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) and Georg Frideric Handel (1685–1759), the orchestra expanded to include woodwind instruments, horns, and drums in addition to the original strings . The castrato soprano voice was frequently given the hero’s part, and castrati were among the greatest stars of the period. The magnificently ornamented music written for such virtuoso singers thrilled audiences but also diminished the dramatic element of opera and provoked calls for reform. These were answered by Christoph Willibald von Gluck (1714–1787), whose Orfeo ed Euridice of 1762 recasts the time-honored operatic story of the artist whose song can thwart death itself.

The reinvigoration of opera at the end of the eighteenth century was assured by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791), whose music for voices and orchestra is alive with dramatic purpose. In The Marriage of Figaro (1786), for example, exquisite melodies describe and enrich the personalities of the clever servant Figaro, his vivacious fiancée Susanna, the lovelorn Countess, the philandering Count, and the eager teenager Cherubino. The extremely effective libretto for this opera, written by Lorenzo Da Ponte (1749–1838), was based on a contemporary French play by Beaumarchais. Don Giovanni (1787), another collaboration between Mozart and Da Ponte, presents the last days of an unrepentant seducer and culminates in two unforgettable scenes in which the statue of a man whom he has murdered accepts an invitation to dinner and arrives to escort him to hell. Mozart’s last opera, a German comedy called The Magic Flute (1791), takes place in fantastic settings that still inspire experiments in set and costume design; two recent productions at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, for instance, were devised by the artists Marc Chagall and David Hockney.

The Flourishing of Opera in the Nineteenth Century In the nineteenth century, conditions were ripe for broadening the audience for opera and for changes in the form itself. Bourgeois taste displaced court concerns in the selection of dramatic subjects, while composers, singers, and theater impresarios vied for popular success. In France and Italy, broad cultural movements like Romanticism , Orientalism , and Realism manifested themselves in opera as in the visual arts, while the rise of nationalism produced vigorous new operatic traditions in Germany and Russia.

The Romantic movement of the early nineteenth century launched a burst of interest in the irrational, the otherworldly, the exotic, and the historical, all subjects admirably suited to operatic portrayal. For instance, Gaetano Donizetti’s (1797–1848) Lucia di Lammermoor (1835), based on a novel by Sir Walter Scott, includes such themes as ancestral enmity, star-crossed love, and the tragic death of the heroine—which, in this case, is preceded by a vocally demanding expression of madness. Similar concerns were paramount in the contemporary French opera, whose leading composer was the German-born Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791–1864). His Robert le Diable (1831), like the several other successful works that he created for the Paris Opéra, was staged with lavish effects, spectacular sets, choreographed dances, and huge onstage ensembles, that is, with all the hallmarks of French grand opera ( 29.100.552 ). The devil himself is a primary character in another example of the genre, Faust (1859), written by Charles Gounod (1818–1893). Because nineteenth-century operas were often based on earlier stage plays or literary works, Romantic subject matter prevailed in opera long after writers and painters had turned to other concerns. Georges Bizet (1838–1875), for example, based his Carmen (1875) on an early nineteenth-century novella by Prosper Mérimée and, like its source, the opera is full of the Spanish flavor that so appealed to French nineteenth-century audiences. The passion, violence, and impropriety so prominently featured in opera ran contrary to the ideals of contemporary bourgeois society, and artists’ portrayals of spectators, particularly women, watching from the privacy of their boxes suggest the constraints placed upon them as well as the attraction of opera’s cathartic subject matter.

High tragedy dominates the operas composed by Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901), whose feeling for drama helped him produce wonderfully expressive music for chorus, ensembles, solo voices, and the orchestra. His first public success came with Nabucco (1842), in which a stirring chorus expresses the longing of captives for their homeland. The plots of Verdi’s operas involve moral conflict and powerful emotions: Rigoletto (1851) presents a court jester whose desire for revenge inadvertently leads to his own daughter’s death; Aida (1871) tells the story of an Ethiopian princess in love with an Egyptian general who represents her country’s enemy; Otello (1887), adapted from Shakespeare , concerns the hero’s fatal jealousy, which results in his undoing and the murder of his wife. Verdi’s operas are full of memorable scenarios, and the exotic settings invite set designers to explore the whole history of art. On stage, the triumphal parade in Aida can evoke the grandeur of pharaonic Egypt , and the arrival of the ambassadors in Otello may resemble a Venetian painting brought to life.

Verdi’s contemporary Richard Wagner (1813–1883) took a completely different approach to opera. His ideal was the Gesamtkunstwerk , or total work of art, in which drama, staging, and music would forge a powerful unity. Wagner realized these aims by controlling every aspect of his works, writing his own librettos and supervising set design as well as composing the music. In many ways, Wagner magnified the opera beyond any proportions it had attained before. He scored his works for a large orchestra, requiring herculean voices to complement it, and he raised in his dramas such profound themes as redemption through love and the rapport between humanity and the divine. His largest project, Der Ring des Nibelungen (1853–74), is a sweeping drama in four parts, each one longer than a standard Italian opera. The story of the Ring , based on Germanic mythology, presents many opportunities for visual spectacle, among them the Rhine Maidens swimming under water, the Valkyries riding in on winged horses, Siegfried’s combat with the dragon Fafner, Brünhilde asleep in the midst of magic flames, and the fall of Valhalla itself. Frustrated with the physical limitations of contemporary theaters, Wagner found the means to build a new house to his own specifications at Bayreuth in Bavaria, and here he departed from established convention by darkening the auditorium during performances and covering the orchestra pit so as to focus all attention on the stage.

The culmination of Wagner’s career in Germany coincided with the building of a new opera house in Paris, designed by Charles Garnier and opened in 1875. The prominent position of the Opéra within the new system of boulevards devised by Baron Haussmann during the Second Empire demonstrates the social importance of opera at the time, while the lavish ornament of the building makes it seem at once a temple and a palace. Among the artists involved in decorating the Opéra were Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, who designed bronze figures carrying candelabra for the grand staircase, and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux , who contributed an animated marble group for the facade ( 11.10 ).

By the late nineteenth century, opera was viewed as the ultimate art form, suitable for portraying the grandest aspirations not only of heroic men and women but also of peoples and nations. The celebrated Russian opera Boris Godunov (1874), written by Modest Mussorgsky (1839–1881), dramatizes a stormy period in Russian history and gives special emphasis to the chorus of common people that crowd around the glittering world of the czar. Although Catherine the Great promoted Italian opera and even wrote some of her own librettos, Russian opera was largely an invention of the nineteenth century, a sign of social ferment as well as rising nationalism. The vigorous Russian literature of the period furnished rich material for such operas as Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s (1840–1893) Eugene Onegin (1879), based (like Boris Godunov ) on a work by Aleksandr Pushkin. Sergei Prokofiev’s (1891–1953) War and Peace and The Gambler were based on works by Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, respectively.

Although the great operatic composers devoted much of their attention to subjects tragic, awesome, or macabre, they also produced comic operas that are still staged and loved. Mozart’s operas contain much that is humorous, both musically and visually. Verdi scored a colossal failure with an early comic opera but ended his career with Falstaff (1893), based on the antics of the jolly Shakespearean knight. The comic operas of Gioacchino Rossini (1792–1868), such as The Barber of Seville (1816), are rife with tunes that brilliantly express fast-paced intrigue in hilarious situations. Even Wagner composed one masterpiece, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1868), with a happy ending and a number of comic features. The setting is sixteenth-century Nuremberg, and the action revolves around a group of craftsmen-singers, foremost among them the shoemaker-poet Hans Sachs. The discussion of art that runs throughout the opera applies specifically to music but may also be extended to other genres; the artist Albrecht Dürer , presumably alive among the characters, is mentioned in the opera.

Opera and the Kinship of the Arts On occasion, the opera has magnified the lives of artists actual and fictional as well as the heroics of warriors, princes, and revolutionaries. The flamboyant sixteenth-century artist Benvenuto Cellini provided material for the eponymous opera (1838) by Hector Berlioz (1803–1869), which culminates in the casting of a bronze statue on stage. More recently, Paul Hindemith (1895–1963) wrote an opera, Mathis der Maler (1938), about the German Renaissance artist Matthias Grünewald, and Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) composed a chamber opera, The Rake’s Progress (1951), inspired by the well-known cycle of satirical prints—and their painted prototypes—by William Hogarth. Artists are among the characters in two of Giacomo Puccini’s (1858–1924) most popular works: Cavaradossi, the leading man in Tosca (1900), is a painter, as is the sympathetic Marcello, companion to the poet Rodolfo, the tragic hero of La Bohème (1898).

Finally, portraits of singers demonstrate the complementary histories of art and opera. Andrea Sacchi’s portrait of Marcantonio Pasqualini (1614–1691) represents the castrato in a classical landscape that evokes the pastoral subjects of much seventeenth-century opera ( 1981.317 ). In a painting by François Hubert Drouais, the eighteenth-century singer Madame Charles Simon Favart (1727–1772) appears in fashionable attire rather than stage costume ( 17.120.210 ), but later portraits capture operatic characters as well as the singers who portrayed them. Gustave Courbet painted the Paris Opéra tenor Louis Gueymard (1822–1880) in the role of Robert, the complicated hero of Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable ( 19.84 ), and Augustus Saint-Gaudens portrayed the soprano Eva Rohr in the costume of Marguerite from Gounod’s Faust ( 1990.317 ). Édouard Manet’s several portraits of the baritone Jean-Baptiste Faure (1830–1914) capture the singer’s piercing eyes and expressive face, which gave credibility to his portrayals of Mephistopheles and Hamlet ( 59.129 ).

Sorabella, Jean. “The Opera.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/opra/hd_opra.htm (October 2004)

Further Reading

Béhar, Pierre, and Helen Watanabe-O'Kelly. Spectaculum Europaeum: Theatre and Spectacle in Europe (1580–1750) . Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1999.

Parker, Roger, ed. The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Sadie, Stanley, ed. History of Opera . New York: Norton, 1990.

Warrack, John, and Ewan West. The Oxford Dictionary of Opera . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Additional Essays by Jean Sorabella

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Pilgrimage in Medieval Europe .” (April 2011)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe .” (August 2007)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Venetian Color and Florentine Design .” (October 2002)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Art of the Roman Provinces, 1–500 A.D. .” (May 2010)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in Baroque and Later Art .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in Western Art and Its Beginnings in Antiquity .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe .” (originally published October 2001, last revised March 2013)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Interior Design in England, 1600–1800 .” (October 2003)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Vikings (780–1100) .” (October 2002)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Painting the Life of Christ in Medieval and Renaissance Italy .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Birth and Infancy of Christ in Italian Painting .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Crucifixion and Passion of Christ in Italian Painting .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Carolingian Art .” (December 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Ottonian Art .” (September 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Ballet .” (October 2004)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Baroque Rome .” (October 2003)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Grand Tour .” (October 2003)

Related Essays

- Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

- François Boucher (1703–1770)

- Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827–1875)

- Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art

- Americans in Paris, 1860–1900

- Baroque Rome

- Commedia dell’arte

- Costume in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- The Countess da Castiglione

- Edgar Degas (1834–1917): Painting and Drawing

- Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770)

- Impressionism: Art and Modernity

- Music in the Renaissance

- Nineteenth-Century Classical Music

- Nineteenth-Century French Realism

- The Nude in Baroque and Later Art

- The Piano: Viennese Instruments

- Poets, Lovers, and Heroes in Italian Mythological Prints

- Renaissance Violins

- Romanticism

- Shakespeare and Art, 1709–1922

- Shakespeare Portrayed

- Theater and Amphitheater in the Roman World

- Theater in Ancient Greece

- Thomas Sully (1783–1872) and Queen Victoria

- Venice in the Eighteenth Century

- Balkan Peninsula, 1900 A.D.–present

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1600–1800 A.D.

- Central Europe and Low Countries, 1800–1900 A.D.

- Central Europe, 1900 A.D.–present

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1800–1900 A.D.

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1900 A.D.–present

- Florence and Central Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- France, 1600–1800 A.D.

- France, 1800–1900 A.D.

- France, 1900 A.D.–present

- Germany and Switzerland, 1900 A.D.–present

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1800–1900 A.D.

- Italian Peninsula, 1900 A.D.–present

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Southern Europe, 1800–1900 A.D.

- The United States and Canada, 1800–1900 A.D.

- The United States and Canada, 1900 A.D.–present

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- 18th Century A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- Baroque Art

- Central Europe

- Central Italy

- Classical Period

- Eastern Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- French Literature / Poetry

- German Literature / Poetry

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Greek Literature / Poetry

- Italian Literature / Poetry

- Literature / Poetry

- Musical Instrument

- Northern Italy

- Orientalism

- Printmaking

- Russian Literature / Poetry

- Sculpture in the Round

- Southern Italy

- United States

Artist or Maker

- Amati, Nicolò

- Boucher, François

- Carpeaux, Jean-Baptiste

- Carrier-Belleuse, Albert-Ernest

- Chagall, Marc

- Courbet, Gustave

- Degas, Edgar

- Drouais, François Hubert

- Hockney, David

- Hogarth, William

- Manet, Édouard

- Sacchi, Andrea

- Saint-Gaudens, Augustus

- Watteau, Antoine

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Winners and Losers” by Xavier Salomon

- Connections: “Opera” by Irina Shifrin

All performances will proceed as scheduled. Learn More

<strong data-cart-timer="" role="text"></strong>

Opera's Late Romantic Era: 1865-1920 “The power of myth”

Opera’s late romantic era, “the power of myth”.

1865-1920: Van Gogh gets a wave of inspiration from Hokusai, the Ottoman Empire fades from view, Andrew Carnegie forges a fortune out of steel, and opera passes a point of no return.

Uncover the driving forces behind opera’s fiercest era, including Europe’s semi-unhealthy obsession with death, desire, and nationalist identity—all of which sparked a wild streak of artistic innovation and some truly iconic music for the stage.

Recommended for grades 6-12.

In this resource, you will:

- Discover how cultural tastes and traditions further divided opera along national lines.

- Meet two game-changing composers who flipped the operatic script.

- Travel to some of opera’s late Romantic strongholds, including Russia and Czechoslovakia.

- Listen to some of opera’s most enduringly popular tunes.

Understanding Opera • Introduction Baroque Era • Classical Era Early Romantic Era • Late Romantic Era The 20th Century • Modern Era

How’re we doing, operagoers? Did you survive the early Romantic era okay? Minds still intact? Bodies properly hydrated? Tissues still handy?

Because, as emotionally draining as those early Romantic operas can be, they pale in comparison to the operas of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Welcome to the late Romantic era , where pain is even more excruciating, happiness is even more ecstatic, passions run even deeper, and the old rules of music no longer apply.

We’re through the looking glass now, folks. No safety net and no turning back.

Good luck. And may the opera odds be ever in your favor.

Opera Gets Extra Patriotic

The story of late Romantic opera is the story of… wait for it… story .

And we’re not talking Cinderella-loses-a-slipper or Hansel-and-Gretel-get-lost-in-the-woods type stories.* We’re talking no-holds-barred, rip-your-heart-out, make-you-rethink-the-way-you’ve-been-living-your-life stories full of blood, sweat, tears, brutal warfare, abject poverty, backstabbing betrayal, international espionage, forbidden romance, tragic sacrifice… basically humanity in its rawest, ugliest, and most bittersweet form.

Like their early Romantic colleagues, late Romantic composers and librettists sometimes fleshed out their tales using intricate details that made the stories seem even more real and relatable. These details came from a number of inspirational sources, but a significant portion of them were born out of national pride.

* Alright, that’s technically a lie. Cinderella and Hansel and Gretel do actually make an appearance in late Romantic opera. But, in our defense, they’re not portrayed the same way they would be in your average ‘Once Upon a Time’ anthology. Instead, these and other late Romantic fairy tales tend to be much more psychologically layered, often forcing their characters into situations of high-stakes physical and emotional risk. (So… not ideal for bedtime.)

As territories like those in Italy, Germany, and Bohemia (Czechoslovakia) started forming sovereign governments of their own (see Welcome to the revolution under the Early Romantic Era ), national identities intensified. Suddenly, more and more opera creators were interested in putting local lore, patriotic myth, historic folk tunes, or well-known works of indigenous literature onto the big stage, all so their home countries could be part of the larger cultural dialogue.

But while each of these territories had unique stories to tell, they also had unique ways of telling them. And this brings us to yet another crossroads question in the history of opera (sort of like the one we encountered with our guys Gluck and Mozart ):

What’s the best way to tell a musical story?

Again, full disclosure: There’s no right or wrong answer here. But much of late Romantic opera is about composers squabbling with each other over the purest, most impactful method of telling a story through song. And two of the most (in)famous composers who found themselves on opposing sides of this colossal debate were Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)—already an opera legend by the 1840s—and Richard Wagner (1813-1883).

Allow us to introduce you to them…

Viva Verdi!

Verdi is one of those names that makes opera fans stop what they’re doing and say: “Respect.” (And if they don’t say it, they’re definitely thinking it.)

Take a look at any current opera season in any major opera house around the world and you’re guaranteed to find at least one Verdi opera on the schedule (but probably more). The reasons for this are too numerous and detailed to cover here, but these are our picks for the top three:

- Verdi wasn’t just a composer, he was an icon. Through a combination of talent, luck, political conviction, and historical accident, his music became a rallying cry for an Italian independence movement known as the Risorgimento or “Resurrection.” His name even became a nationalist code word, as the initials V, E, R, D, and I were a not-so-secret acronym that spelled out undying support for Risorgimento leader Vittorio Emanuele II.*

- Verdi understood that differences in vocal volume, color, strength, and agility could represent different facets of human nature, and he assigned his singing roles accordingly. Verdi vocalists don’t just sing about emotions, they actually sound like whatever it is they’re feeling. As a result, his characters—and their dramatic dilemmas—are extremely hard to forget

- He had an eye (and an ear) for great stories.

*The full code was “Vittorio Emanuele II, rei d’Italia” or “Vittorio Emanuele II, king of Italy.” Resurrectionists would reportedly shout, “Viva Verdi !” in solidarity with Italian independence, giving both Vittorio Emanuele II and Giuseppe Verdi a steady stream of national publicity.

Verdi was a consummate dramatist. Now, to be fair, his operas were often based on tales by heavy literary hitters like Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas fils, and William Shakespeare … so it’s not like he didn’t have a lot to work with. But miraculously, Verdi was able to zoom in on moments that packed the biggest dramatic punch, distill them down to their most basic and most powerful fundamentals, and then unleash them on his audience through a carefully calibrated balance of voice and instrumentals.