/images/cornell/logo35pt_cornell_white.svg" alt="what is a research statement for a job application"> Cornell University --> Graduate School

Research statement, what is a research statement.

The research statement (or statement of research interests) is a common component of academic job applications. It is a summary of your research accomplishments, current work, and future direction and potential of your work.

The statement can discuss specific issues such as:

- funding history and potential

- requirements for laboratory equipment and space and other resources

- potential research and industrial collaborations

- how your research contributes to your field

- future direction of your research

The research statement should be technical, but should be intelligible to all members of the department, including those outside your subdiscipline. So keep the “big picture” in mind. The strongest research statements present a readable, compelling, and realistic research agenda that fits well with the needs, facilities, and goals of the department.

Research statements can be weakened by:

- overly ambitious proposals

- lack of clear direction

- lack of big-picture focus

- inadequate attention to the needs and facilities of the department or position

Why a Research Statement?

- It conveys to search committees the pieces of your professional identity and charts the course of your scholarly journey.

- It communicates a sense that your research will follow logically from what you have done and that it will be different, important, and innovative.

- It gives a context for your research interests—Why does your research matter? The so what?

- It combines your achievements and current work with the proposal for upcoming research.

- areas of specialty and expertise

- potential to get funding

- academic strengths and abilities

- compatibility with the department or school

- ability to think and communicate like a serious scholar and/or scientist

Formatting of Research Statements

The goal of the research statement is to introduce yourself to a search committee, which will probably contain scientists both in and outside your field, and get them excited about your research. To encourage people to read it:

- make it one or two pages, three at most

- use informative section headings and subheadings

- use bullets

- use an easily readable font size

- make the margins a reasonable size

Organization of Research Statements

Think of the overarching theme guiding your main research subject area. Write an essay that lays out:

- The main theme(s) and why it is important and what specific skills you use to attack the problem.

- A few specific examples of problems you have already solved with success to build credibility and inform people outside your field about what you do.

- A discussion of the future direction of your research. This section should be really exciting to people both in and outside your field. Don’t sell yourself short; if you think your research could lead to answers for big important questions, say so!

- A final paragraph that gives a good overall impression of your research.

Writing Research Statements

- Avoid jargon. Make sure that you describe your research in language that many people outside your specific subject area can understand. Ask people both in and outside your field to read it before you send your application. A search committee won’t get excited about something they can’t understand.

- Write as clearly, concisely, and concretely as you can.

- Keep it at a summary level; give more detail in the job talk.

- Ask others to proofread it. Be sure there are no spelling errors.

- Convince the search committee not only that you are knowledgeable, but that you are the right person to carry out the research.

- Include information that sets you apart (e.g., publication in Science, Nature, or a prestigious journal in your field).

- What excites you about your research? Sound fresh.

- Include preliminary results and how to build on results.

- Point out how current faculty may become future partners.

- Acknowledge the work of others.

- Use language that shows you are an independent researcher.

- BUT focus on your research work, not yourself.

- Include potential funding partners and industrial collaborations. Be creative!

- Provide a summary of your research.

- Put in background material to give the context/relevance/significance of your research.

- List major findings, outcomes, and implications.

- Describe both current and planned (future) research.

- Communicate a sense that your research will follow logically from what you have done and that it will be unique, significant, and innovative (and easy to fund).

Describe Your Future Goals or Research Plans

- Major problem(s) you want to focus on in your research.

- The problem’s relevance and significance to the field.

- Your specific goals for the next three to five years, including potential impact and outcomes.

- If you know what a particular agency funds, you can name the agency and briefly outline a proposal.

- Give broad enough goals so that if one area doesn’t get funded, you can pursue other research goals and funding.

Identify Potential Funding Sources

- Almost every institution wants to know whether you’ll be able to get external funding for research.

- Try to provide some possible sources of funding for the research, such as NIH, NSF, foundations, private agencies.

- Mention past funding, if appropriate.

Be Realistic

There is a delicate balance between a realistic research statement where you promise to work on problems you really think you can solve and over-reaching or dabbling in too many subject areas. Select an over-arching theme for your research statement and leave miscellaneous ideas or projects out. Everyone knows that you will work on more than what you mention in this statement.

Consider Also Preparing a Longer Version

- A longer version (five–15 pages) can be brought to your interview. (Check with your advisor to see if this is necessary.)

- You may be asked to describe research plans and budget in detail at the campus interview. Be prepared.

- Include laboratory needs (how much budget you need for equipment, how many grad assistants, etc.) to start up the research.

Samples of Research Statements

To find sample research statements with content specific to your discipline, search on the internet for your discipline + “Research Statement.”

- University of Pennsylvania Sample Research Statement

- Advice on writing a Research Statement (Plan) from the journal Science

- Appointments

- Resume Reviews

- Undergraduates

- PhDs & Postdocs

- Faculty & Staff

- Prospective Students

- Online Students

- Career Champions

- I’m Exploring

- Architecture & Design

- Education & Academia

- Engineering

- Fashion, Retail & Consumer Products

- Fellowships & Gap Year

- Fine Arts, Performing Arts, & Music

- Government, Law & Public Policy

- Healthcare & Public Health

- International Relations & NGOs

- Life & Physical Sciences

- Marketing, Advertising & Public Relations

- Media, Journalism & Entertainment

- Non-Profits

- Pre-Health, Pre-Law and Pre-Grad

- Real Estate, Accounting, & Insurance

- Social Work & Human Services

- Sports & Hospitality

- Startups, Entrepreneurship & Freelancing

- Sustainability, Energy & Conservation

- Technology, Data & Analytics

- DACA and Undocumented Students

- First Generation and Low Income Students

- International Students

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Transfer Students

- Students of Color

- Students with Disabilities

- Explore Careers & Industries

- Make Connections & Network

- Search for a Job or Internship

- Write a Resume/CV

- Write a Cover Letter

- Engage with Employers

- Research Salaries & Negotiate Offers

- Find Funding

- Develop Professional and Leadership Skills

- Apply to Graduate School

- Apply to Health Professions School

- Apply to Law School

- Self-Assessment

- Experiences

- Post-Graduate

- Jobs & Internships

- Career Fairs

- For Employers

- Meet the Team

- Peer Career Advisors

- Career Services Policies

- Walk-Ins & Pop-Ins

- Strategic Plan 2022-2025

Research statements for faculty job applications

The purpose of a research statement.

The main goal of a research statement is to walk the search committee through the evolution of your research, to highlight your research accomplishments, and to show where your research will be taking you next. To a certain extent, the next steps that you identify within your statement will also need to touch on how your research could benefit the institution to which you are applying. This might be in terms of grant money, faculty collaborations, involving students in your research, or developing new courses. Your CV will usually show a search committee where you have done your research, who your mentors have been, the titles of your various research projects, a list of your papers, and it may provide a very brief summary of what some of this research involves. However, there can be certain points of interest that a CV may not always address in enough detail.

- What got you interested in this research?

- What was the burning question that you set out to answer?

- What challenges did you encounter along the way, and how did you overcome these challenges?

- How can your research be applied?

- Why is your research important within your field?

- What direction will your research take you in next, and what new questions do you have?

While you may not have a good sense of where your research will ultimately lead you, you should have a sense of some of the possible destinations along the way. You want to be able to show a search committee that your research is moving forward and that you are moving forward along with it in terms of developing new skills and knowledge. Ultimately, your research statement should complement your cover letter, CV, and teaching philosophy to illustrate what makes you an ideal candidate for the job. The more clearly you can articulate the path your research has taken, and where it will take you in the future, the more convincing and interesting it will be to read.

Separate research statements are usually requested from researchers in engineering, social, physical, and life sciences, but can also be requested for researchers in the humanities. In many cases, however, the same information that is covered in the research statement is often integrated into the cover letter for many disciplines within the humanities and no separate research statement is requested within the job advertisement. Seek advice from current faculty and new hires about the conventions of your discipline if you are in doubt.

Timeline: Getting Started with Your Research Statement

You can think of a research statement as having three distinct parts. The first part will focus on your past research and can include the reasons you started your research, an explanation as to why the questions you originally asked are important in your field, and a summary some of the work you did to answer some of these early questions.

The middle part of the research statement focuses on your current research. How is this research different from previous work you have done, and what brought you to where you are today? You should still explain the questions you are trying to ask, and it is very important that you focus on some of the findings that you have (and cite some of the publications associated with these findings). In other words, do not talk about your research in abstract terms, make sure that you explain your actual results and findings (even if these may not be entirely complete when you are applying for faculty positions), and mention why these results are significant.

The final part of your research statement should build on the first two parts. Yes, you have asked good questions and used good methods to find some answers, but how will you now use this foundation to take you into your future? Since you are hoping that your future will be at one of the institutions to which you are applying, you should provide some convincing reasons why your future research will be possible at each institution, and why it will be beneficial to that institution and to their students.

While you are focusing on the past, present, and future or your research, and tailoring it to each institution, you should also think about the length of your statement and how detailed or specific you make the descriptions of your research. Think about who will be reading it. Will they all understand the jargon you are using? Are they experts in the subject, or experts in a range of related subjects? Can you go into very specific detail, or do you need to talk about your research in broader terms that make sense to people outside of your research field, focusing on the common ground that might exist? Additionally, you should make sure that your future research plans differ from those of your PI or advisor, as you need to be seen as an independent researcher. Identify 4-5 specific aims that can be divided into short-term and long-term goals. You can give some idea of a 5-year research plan that includes the studies you want to perform, but also mention your long-term plans so that the search committee knows that this is not a finite project.

Another important consideration when writing about your research is realizing that you do not perform research in a vacuum. When doing your research, you may have worked within a team environment at some point or sought out specific collaborations. You may have faced some serious challenges that required some creative problem-solving to overcome. While these aspects are not necessarily as important as your results and your papers or patents, they can help paint a picture of you as a well-rounded researcher who is likely to be successful in the future even if new problems arise, for example.

Follow these general steps to begin developing an effective research statement:

Step 1: Think about how and why you got started with your research. What motivated you to spend so much time on answering the questions you developed? If you can illustrate some of the enthusiasm you have for your subject, the search committee will likely assume that students and other faculty members will see this in you as well. People like to work with passionate and enthusiastic colleagues. Remember to focus on what you found, what questions you answered, and why your findings are significant. The research you completed in the past will have brought you to where you are today; also be sure to show how your research past and research present are connected. Explore some of the techniques and approaches you have successfully used in your research, and describe some of the challenges you overcame. What makes people interested in what you do, and how have you used your research as a tool for teaching or mentoring students? Integrating students into your research may be an important part of your future research at your target institutions. Conclude describing your current research by focusing on your findings, their importance, and what new questions they generate.

Step 2: Think about how you can tailor your research statement for each application. Familiarize yourself with the faculty at each institution, and explore the research that they have been performing. You should think about your future research in terms of the students at the institution. What opportunities can you imagine that would allow students to get involved in what you do to serve as a tool for teaching and training them, and to get them excited about your subject? Do not talk about your desire to work with graduate students if the institution only has undergraduates! You will also need to think about what equipment or resources that you might need to do your future research. Again, mention any resources that specific institutions have that you would be interested in utilizing (e.g., print materials, super electron microscopes, archived artwork). You can also mention what you hope to do with your current and future research in terms of publication (whether in journals or as a book); try to be as specific and honest as possible. Finally, be prepared to talk about how your future research can help bring in grants and other sources of funding, especially if you have a good track record of receiving awards and fellowships. Mention some grants that you know have been awarded to similar research, and state your intention to seek this type of funding.

Step 3: Ask faculty in your department if they are willing to share their own research statements with you. To a certain extent, there will be some subject-specific differences in what is expected from a research statement, and so it is always a good idea to see how others in your field have done it. You should try to draft your own research statement first before you review any statements shared with you. Your goal is to create a unique research statement that clearly highlights your abilities as a researcher.

Step 4: The research statement is typically a few (2-3) pages in length, depending on the number of images, illustrations, or graphs included. Once you have completed the steps above, schedule an appointment with a career advisor to get feedback on your draft. You should also try to get faculty in your department to review your document if they are willing to do so.

Additional Resources

For further tips, tricks, and strategies for writing a research statement for faculty jobs, see the resources below:

- The PhD Career Training Platform is an eLearning platform with on-demand, self-paced modules that allow PhDs and postdocs to make informed decisions about their career path and learn successful job search strategies from other PhDs. Select the University of Pennsylvania from the drop-down menu, log in using your University ID, and click the “Faculty Careers” tab to learn more about application documents for a faculty job search.

- Writing an Effective Research Statement

- Research Statements for Humanities PhDs

- Tips to Get Started on Your Research Statement (video)

Explore other application documents:

Faculty Applications: Research Statement

1. introduction.

The purpose of this CommKit is to help guide you through exercises to write your faculty application research statement. After reading this document, you will be able to outline your faculty research statement and effectively demonstrate both your research vision and unique attributes that make you the best candidate for the job.

Table of Contents

2. Criteria for Success

A successful research statement will:

- Explain your overall research vision.

- Explain why your proposed research is important

- Explain why you can achieve your vision.

- Explain how you will achieve your vision

- Explain who will support your research.

Your research statement in your faculty application package serves to quickly and effectively communicate your vision for your future research as a faculty member.

The faculty search committee uses this statement to evaluate:

- Your creativity and ability to identify worthwhile research topics

- Your technical communication skills

- Your knowledge of the field

- Whether you would be an interesting and productive colleague

- Your “fit” with the institution

- Your overlap with existing research areas

- Your possibility to develop new areas where they want to grow

- Your ability to get funding for your work and for the university

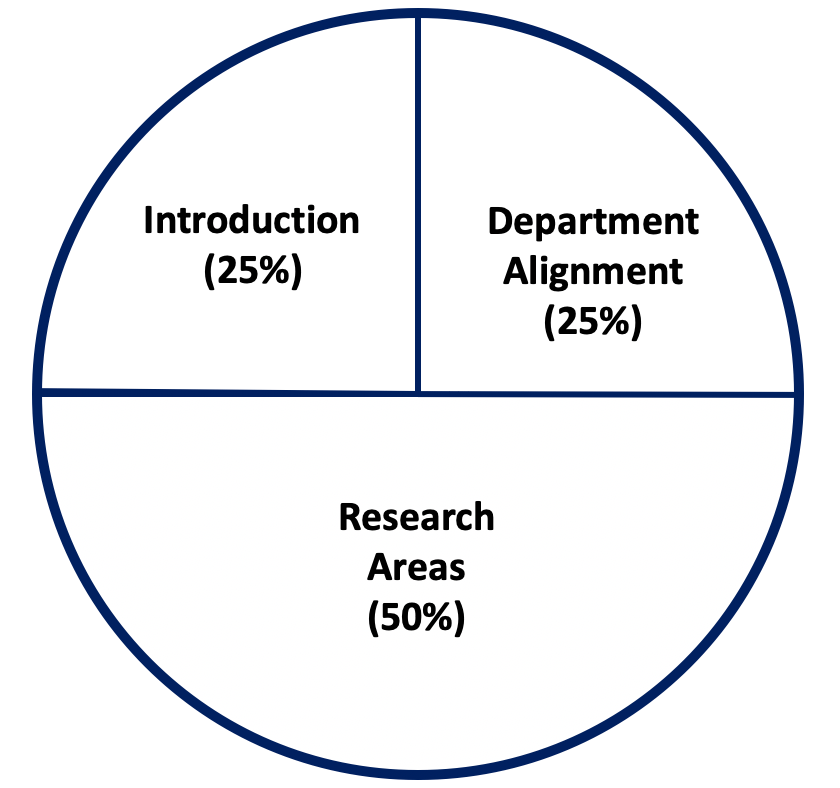

4. Structure Diagram

In aerospace engineering, research statements are 2-4 pages long, with a focus on past and current work. Research statements typically have the following content breakdown shown in the pie chart below.

While there are no strict rules, we recommend this general ratio of introduction, department alignment, and research areas for your faculty research statement .

There is no mandated structure for a research statement, but we recommend the following elements.

Introduction:

Explains your research vision, the problems you seek to address, why these problems are important, your core research areas, and your specific “brand” or assets you bring to the position.

Research Areas:

Highlights your 2-3 core research areas and provides supplemental examples of your work in these areas. This can be a mixture of your previous work and how it would inform your future work, and also future research directions you are going to pursue as faculty. You should highlight why each direction you want to pursue is important, and what expected outcomes or impact could come from these research directions.

Departmental Alignment:

Explains your alignment with the department and helps characterize how you will behave as faculty. There are many different approaches you can take to this section, and there is no expectation for what exactly you should include. Some examples of what is commonly put in this section are:

- 1-2 specific PhD projects your future students will pursue

- Sources that you will seek funding from

- People you would collaborate with in the department

- Department research initiatives that align with your work

- University research initiatives that align with your work.

Your department alignment can be interwoven with your research areas. You don’t necessarily need to keep these elements completely separate from your research areas, it depends on the nature of your work, the school you are applying to, and how you structure your statement overall (see the attached annotated examples for some references).

5. Analyze Your Audience

Your research statement will change depending on the school you are applying to. If you are applying to an R1 institute, your research vision will need to connect with the strengths of the department, funding opportunities available, and the job posting itself. Conversely, if you are applying to an undergraduate only, teaching focused school, your material will need to mention more opportunities for undergraduate research. If you are applying to jobs outside of your major, you may need to alter your research vision to feature more application specific examples and background to convey your interest in the field and the relevance of your work.

Faculty postings can receive upwards of 200-300 applicants. Not every faculty search member is going to read your entire research statement, and they certainly aren’t all going to read it thoroughly. Structure your research statement so that readers can understand what you want to do in 20 seconds, 2 minutes and 10 minutes.

20 second readers – Your introduction is critical to succinctly defining your research vision and brand as a faculty member. Your reader needs to understand this vision immediately from the first few sentences of your research statement. 20 second readers are ones that only want to broadly understand the class of problems you are interested in exploring.

2 minute readers – This class of reader is interested in knowing how you will solve the problems you highlight in the introduction. These readers need to easily be able to find your 2-3 core research areas. Ensure that on the first page of your research statement, you mention core areas you will pursue. Formatting can also be your friend here, selectively bolded headings can make your research statement easier to scan, and can reiterate your research areas. It is also becoming increasingly common to include figures in your research statement. Figures can help show the relationship between your research vision and your specific research areas, and also succinctly summarize what your overall statement is about.

10 minute readers – These are your ideal readers that are going to actually read the full document. They are interested in your past projects, and what you envision being faculty at the university will be like. Make sure you have included enough details in the document so that these readers can understand both the significance of your past work, and how it informs your future work. Minor implementation details are not appropriate for your research statement, those can be left to a job talk you will give later in the process.

6. Best Practices

6.1. research what universities that you are interested in applying to..

When preparing to go on the academic job market, it’s important to research what schools are hiring and what universities that you would be interested in working at. Some common job websites that post open faculty positions are HigherEdJobs and AcademicJobsOnline . We recommend creating a spreadsheet so that you can track positions you are interested in, what materials they expect you to submit, and their associated deadline.

6.2. Write a 1-2 sentence statement that summarizes your research vision and why it is important.

Nailing this sentence description is the hardest aspect of putting a faculty application together. This one sentence is the key brand identification – what specifically do you want to do using only non-jargon words.

A research vision answers what is the impact of your research on a 20 year scale. You have to think big. If all your first research ideas worked perfectly, would your research vision still be viable? Avoid the trap of thinking too small or tailoring your work too much to a problem that only exists in the current moment.

One common misconception with research visions is to write it in the same tone as you would a traditional research proposal grant. Faculty research visions require you to think much bigger, your faculty research statement must explain why you would change the world. Some example faculty research vision statements are included in the annotated examples of this CommKit.

6.3. Identify what sets you apart.

List what unique aspects of your training or research set you apart from other applicants. In the outlining stage, try to keep this to a 1-2 two sentence summary. Having this shortened summary forces you to succinctly identify your unique attributes, which will be useful for. This brief summary can also be integrated into your brief introduction at the start of the statement, where you are clearly articulating both your vision, and why you specifically are the best to pursue it.

If you are struggling to identify what sets you apart, review your CV. We list a few bulleted ideas below for possible attributes you could highlight:

- Awards you have received

- Specific sub-disciplines or fields you work in.

- Teaching experiences that you have had

- Leadership experiences you’ve had

- Methods you rely on, and how your methods inform your research vision

6.4 Define 2-3 core research areas that you will pursue that support your research vision

These research areas will become the key supports to your research vision. As stated before, the research vision serves to articulate a huge goal about the potential impact of your research. The research areas answer how exactly you will be able to accomplish that goal.

Unlike your research vision, which should avoid jargon, your description of your research areas should be more technical. It is fine to assume readers at this point are people from your field, so you can increase the level of jargon if it improves the clarity of what you are saying. Mention sub-disciplines in your field, methods, and specific outcomes of these research areas. Your research areas serve to answer what your research lab will actually work on, providing insight to the type of conferences and journals your students would submit to, and your possible collaborators in the department.

There are a few tricky parts to defining your research areas. First, you should be leveraging your prior research experience, but not creating a derivative of it. Remember, you are applying to a faculty application, not for Ph.D. Part II. You need to differentiate your research areas from the work you did in your Ph.D. and from the work your advisor does. This demonstrates that you have both the maturity of a faculty member and the concrete research vision.

Second, you need to add enough specifics to give credibility but leave the reader space to riff on your ideas. Ideally, you want the faculty readers of your application to read your research and be able to envision how they could collaborate with you based on the descriptions of your work. This means you can skip more minor details from your prior work and leave those as questions you can answer in future interview stages. Finding a balance in the level of detail can be a hard balance to strike, and it is definitely valuable to get feedback from those both inside and outside your field specialty on their impression of your research areas from the research statement.

6.5. Include forward looking statements

Be wary of overemphasizing your Ph.D. or Postdoc training and work that you did in prior labs. Include statements that are forward looking such as “My lab will.” Instead of having a huge section that is just listing your prior work, integrate your prior Ph.D. work into your research areas.

6.6. Revise and Iterate, Iterate, Iterate,

Working on your job application package is a lot of work. Each faculty application should be tailored to the university itself. Start early and invest the time to create a good product. It is important to get feedback about your research statement from colleagues from different backgrounds and seniority. Note that it might take time for other people to share their feedback, so plan ahead!

Remember that you are always welcome to make an appointment with an AeroAstro Communication Fellow to obtain additional feedback on your statements.

References:

[1] MIT EECS Comm Lab: Faculty Application: Research Statement CommKit

[2] MIT CAPD “Path of Professorship Workshop”

[3] Nexus NextProf Faculty Workshop

Resources and Annotated Examples

Annotated research statement 1.

Annotated research statement from a faculty application. 243 KB

Annotated Research Statement 2

Annotated research statement from a faculty application. 253 KB

Understanding and solving intractable resource governance problems.

- Conferences and Talks

- Exploring models of electronic wastes governance in the United States and Mexico: Recycling, risk and environmental justice

- The Collaborative Resource Governance Lab (CoReGovLab)

- Water Conflicts in Mexico: A Multi-Method Approach

- Past projects

- Publications and scholarly output

- Research Interests

- Higher education and academia

- Public administration, public policy and public management research

- Research-oriented blog posts

- Stuff about research methods

- Research trajectory

- Publications

- Developing a Writing Practice

- Outlining Papers

- Publishing strategies

- Writing a book manuscript

- Writing a research paper, book chapter or dissertation/thesis chapter

- Everything Notebook

- Literature Reviews

- Note-Taking Techniques

- Organization and Time Management

- Planning Methods and Approaches

- Qualitative Methods, Qualitative Research, Qualitative Analysis

- Reading Notes of Books

- Reading Strategies

- Teaching Public Policy, Public Administration and Public Management

- My Reading Notes of Books on How to Write a Doctoral Dissertation/How to Conduct PhD Research

- Writing a Thesis (Undergraduate or Masters) or a Dissertation (PhD)

- Reading strategies for undergraduates

- Social Media in Academia

- Resources for Job Seekers in the Academic Market

- Writing Groups and Retreats

- Regional Development (Fall 2015)

- State and Local Government (Fall 2015)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2016)

- Regional Development (Fall 2016)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2018)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2019)

- Public Policy Analysis (Spring 2016)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Summer Session 2011)

- POLI 352 Comparative Politics of Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 2)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Term 1)

- POLI 332 Latin American Environmental Politics (Term 2, Spring 2012)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

Preparing a research statement for an academic job application

This is not my first blog post on research statements (this one on research statements and research trajectories and this other on research pipelines, research trajectories and research programmes are quite related), but this is perhaps the first time I write about and address the Research Statement as a key component of job applications for tenure-track or post-doctoral positions. We all know how angry and upset I feel about the dismal state of the academic job market(s). However, let us assume that you still want to apply for tenure-track (TT) jobs. I do have some experience applying for (and landing) TT jobs, as well as chairing search committees for these positions. I have also sat on search committees, and have read hundreds of applications. These are thus a few pointers that I think might help potential applicants write their statements.

We all know the huge role that luck, connections, institutional “pedigree” and other factors play, but for purposes of helping those who want to apply, some ideas that you all may want to consider in crafting your Research Statements. This blog post started as a Twitter thread so I’ve pulled from there too.

One way to write your research statement is to follow a similar model to the blog post I wrote here https://t.co/A3FaGQkeCU DO NOTE: In this post, I wrote about writing a Research Statement and crafting a Research Trajectory. This was not by chance. There’s a logic to this. — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) July 25, 2020

Personally, I think that when departments and universities hire you, they want to see how you develop your work through time . In that sense, the Research Statement that you arrive with (at the time of application) is STATIC . You present a SNAPSHOT of what you’ve done so far.

In my personal view (please don’t take my suggestions as dogma or guidelines!), I think that there is value in developing both a Research Statement and a Research Trajectory (this one is worth considering in both ex-ante and ex-post modes)

A Research Trajectory can one (or both) of two things:

1) it can present a narrative in timeline form of how your thinking has evolved.

2) it can present your Research Plan for the next 5-6 years (pandemics and life will obviously derail that plan!)

So what I have done with my own Research Statements is to present how my research interests have evolved through time. In that sense, my Research Statement is a STATIC snapshot at a certain point in time (at the time of writing, of course!) of how my different research strands have evolved through time (that is, of my Research Trajectory ). Below is an example of how I have done self-reflection about my own Research Statement.

Last year I was invited to participate in a global workshop of a few selected scholars on the future of environmental policy, which surprised a couple of people. Well, here’s the thing: at the beginning of my career, I *was* a specialist in environmental policy instruments.

Now, my own thinking about the importance, value, structure and content of the Research Plan, Research Trajectory, Research Pipeline and Research Statement has evolved (most recent iteration can be found here https://t.co/nNMDnKa3Gm ) What must be clear from my blog is that… — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) July 25, 2020

… to observe and read many Research Statements (or research narratives, as you may want to call them), but I recently came across @paullagunes ‘ revamped website, and I really, really liked how he narrates his work https://t.co/dWdYJbHjvT Paul explains his projects through time — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) July 25, 2020

Paul also explains very well how his work contributes to theoretical debates and the empirical literature. Paul is an excellent writer and you may consider reading through his website and published work to see how he crafts his narratives.

If people want to learn more about how to craft a Research Statement, I think one strategy would be to poke around and read the “Research” pages of various scholars’ websites to find patterns. That is how I have learned much of what I now write about, by looking at many scholars’ strategies, distilling them and adapting them into something that works FOR ME.

I said I had two pieces of advice. But in reality, I think it’s just that one: for me, a Research Statement of a candidate tells me what they’ve done, if/where it is published or under review, and how those pieces of work fit a coherent, cohesive narrative of their research .

As someone with interdisciplinary training who continues to do interdisciplinary work, I often struggle when people want to categorize me (am I a geographer, a political scientist, a public administration scholar, a sociologist?). Truth be told, the way I have made peace with this challenge of being interdisciplinary when being in disciplinary departments (who say they want interdisciplinarity but judge you by their disciplinary norms) is to show how my work speaks to the debates of their discipline.

Also, my work (though it cuts through different disciplines and methods), is centred around ONE key question that has puzzled me my entire life: what drives agents to cooperate and collaborate? ?

Studying collaborative behaviour has led me to write on environmental activism and transnational coalitions.

And yes, I study cooperation and collaboration, but often times there are factors that preclude these and lead to disputes, which is why I ALSO study protests, activist mobilization and conflict: https://t.co/cwOJ6mkrcO Studying water conflict has led me to study this resource. — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) July 25, 2020

… the study of cooperation and conflict for the governance of orthodox and unorthodox commons (or common pool resources). Anyhow, just my two cents in hopes this thread may help those crafting their research statements. </end thread> — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) July 25, 2020

You can share this blog post on the following social networks by clicking on their icon.

Posted in academia .

Tagged with research pipeline , research plan , research statement , research trajectory .

No comments

By Raul Pacheco-Vega – July 31, 2020

0 Responses

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post .

Leave a Reply Cancel Some HTML is OK

Name (required)

Email (required, but never shared)

or, reply to this post via trackback .

About Raul Pacheco-Vega, PhD

Find me online.

My Research Output

- Google Scholar Profile

- Academia.Edu

- ResearchGate

My Social Networks

- Polycentricity Network

Recent Posts

- The value and importance of the pre-writing stage of writing

- My experience teaching residential academic writing workshops

- “State-Sponsored Activism: Bureaucrats and Social Movements in Brazil” – Jessica Rich – my reading notes

- Reading Like a Writer – Francine Prose – my reading notes

- Using the Pacheco-Vega workflows and frameworks to write and/or revise a scholarly book

Recent Comments

- Raul Pacheco-Vega on Online resources to help students summarize journal articles and write critical reviews

- Muhaimin Abdullah on Writing journal articles from a doctoral dissertation

- Muhaimin Abdullah on Writing theoretical frameworks, analytical frameworks and conceptual frameworks

- Joseph G on Using the rhetorical precis for literature reviews and conceptual syntheses

- Alma Rangel on Improving your academic writing: My top 10 tips

Follow me on Twitter:

Proudly powered by WordPress and Carrington .

Carrington Theme by Crowd Favorite

Baylor Graduate Writing Center

Helping Grad Students Become Better Writers

Writing a Research Statement: A Brief Overview and Tips for Success

Jasmine Stovall, Consultant

Research statements have become an increasingly common required component of job application materials for positions in academia, specifically those that are research focused. The purpose of this blog post is to provide a brief overview of what a research statement is, why they are important, how they differ from other job application materials, and offer some tips and helpful advice for writing one.

What is a research statement?

To begin, let’s first discuss what a research statement is. Whether you are new to the job application material world or just need a refresher, this is always a great starting point. Having a clear definition of the type of writing you are setting out to do will help you to set more precise writing goals and develop an outline that is in alignment with the required and expected content of the genre as well as any job or field specific conventions.

A research statement is generally defined as a written summary of your research experiences past, present, and future ( Writing a Research Statement-Purdue OWL ). Specifically, it highlights your previous accomplishments (most often your thesis, dissertation, or postdoc research), any current projects you are working on, and proposed projects for the future ( Research Statement-Cornell University ).

Why is it important?

Research statements are important because they allow a hiring committee to evaluate your academic journey and get to know you, not just as a student but also as a professional researcher and active member of the scholarly community. They further allow you as the applicant to inform the committee of what exactly it is that you do, how your previous and future work aligns with the position to which you are applying, how you would be an asset to the department, and ways in which your scope of research can potentially form fruitful collaborations with existing faculty, partnerships with other industries, and engage students. And on a broader scale, the research statement highlights how your research interests and areas of expertise will bring funding to the university and advance the research status of the institution.

How is it different from a CV, cover letter, etc.?

The biggest differences between a research statement and most other job application materials, particularly a CV, are the length and the style of content. While CVs can be several pages, research statements tend to be shorter (three pages maximum) and discuss your research projects detail, rather than as a brief line on your CV. Another difference is that a research statement discusses proposed research, which is generally uncommon for CVs.

Research statements are different from cover letters in that the subject matter is narrower, with your work as the central focus more so than yourself as a person. Cover letters are generally all-encompassing, highlighting hard and soft skills and speaking to your accomplishments personally, professionally, and academically. They make you stand out while also expressing your interest in the position you are applying for and showing why you would be the ideal candidate.

Tips and Helpful Advice for Getting Started

As is the case with most writing projects, the hardest part is getting started. Listed below are some helpful tips to keep in mind and use as a guide when beginning to write your research statement.

- Use your CV – While the CV differs from a research statement, it still contains a plethora of valuable information as it relates to your research projects and accomplishments, making it a great starting point when it comes to outlining your research statement, deciding which information to include, how to structure it, etc. So, don’t hesitate to lean on it to get the ball rolling if you find yourself stuck.

- Focus on examples – Rather than just stating what you’ve done and would like to do, be sure to use specific examples to describe how your research findings have contributed to the scholarly community and the different ways your proposed future research will continue to build upon that. Don’t be afraid to showcase your work ( Writing a Research Statement-Carnegie Mellon University ).

- Make connections – When brainstorming ideas for your research statement, let the main themes of your research and the problems you have tackled or plan to tackle within that main theme serve as a guide in your thought process. When writing, try to prioritize drawing upon these main themes, keeping the big picture and your ‘why’ in mind, then make connections between these main themes/big picture ideas and your specific research goals.

- Be clear, concise, and realistic – Remember that there will be people from various subdisciplines reading your research statement. Therefore, it is important to be mindful of your audience when it comes to the use of technical jargon and overall word choice. This is where having peer reviewers outside of your field can be helpful.

I hope you found this blog post to be helpful. Should you find yourself in need of a second set of eyes to look over your research statement draft or to help with the drafting process, feel free to reach out to the GWC to schedule a consultation.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

What is a Research Statement? The research statement (or statement of research interests) is a common component of academic job applications. It is a summary of your research accomplishments, current work, and future direction and potential of your work.

The main goal of a research statement is to walk the search committee through the evolution of your research, to highlight your research accomplishments, and to show where your research will be taking you next.

Purpose. Your research statement in your faculty application package serves to quickly and effectively communicate your vision for your future research as a faculty member. The faculty search committee uses this statement to evaluate: Your creativity and ability to identify worthwhile research topics. Your technical communication skills.

A Research Trajectory can one (or both) of two things: 1) it can present a narrative in timeline form of how your thinking has evolved. 2) it can present your Research Plan for the next 5-6 years (pandemics and life will obviously derail that plan!)

The research statement describes your research experiences, interests, and plans. Research statements are often requested as part of the faculty application process. Expectations for research statements vary among disciplines.

The purpose of this blog post is to provide a brief overview of what a research statement is, why they are important, how they differ from other job application materials, and offer some tips and helpful advice for writing one.