Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 01 March 2024

The prospect of artificial intelligence to personalize assisted reproductive technology

- Simon Hanassab ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9112-0486 1 , 2 , 3 na1 ,

- Ali Abbara 1 , 4 na1 ,

- Arthur C. Yeung 1 , 4 ,

- Margaritis Voliotis 5 , 6 , 7 ,

- Krasimira Tsaneva-Atanasova ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6294-7051 5 , 6 , 7 ,

- Tom W. Kelsey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8091-1458 8 ,

- Geoffrey H. Trew 1 , 9 ,

- Scott M. Nelson 9 , 10 , 11 ,

- Thomas Heinis 2 na2 &

- Waljit S. Dhillo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5950-4316 1 , 4 na2

npj Digital Medicine volume 7 , Article number: 55 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

10 Citations

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Endocrine reproductive disorders

- Infertility

- Machine learning

Infertility affects 1-in-6 couples, with repeated intensive cycles of assisted reproductive technology (ART) required by many to achieve a desired live birth. In ART, typically, clinicians and laboratory staff consider patient characteristics, previous treatment responses, and ongoing monitoring to determine treatment decisions. However, the reproducibility, weighting, and interpretation of these characteristics are contentious, and highly operator-dependent, resulting in considerable reliance on clinical experience. Artificial intelligence (AI) is ideally suited to handle, process, and analyze large, dynamic, temporal datasets with multiple intermediary outcomes that are generated during an ART cycle. Here, we review how AI has demonstrated potential for optimization and personalization of key steps in a reproducible manner, including: drug selection and dosing, cycle monitoring, induction of oocyte maturation, and selection of the most competent gametes and embryos, to improve the overall efficacy and safety of ART.

Similar content being viewed by others

Optimizing oocyte yield utilizing a machine learning model for dose and trigger decisions, a multi-center, prospective study

Machine learning for sperm selection

Pseudo contrastive labeling for predicting IVF embryo developmental potential

Introduction.

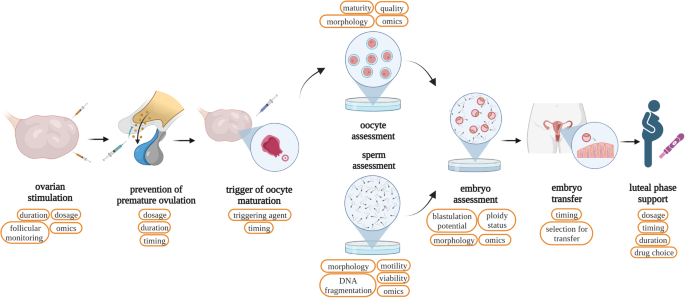

Since the birth of the first baby conceived through in vitro fertilization (IVF) in 1978, the development of assisted reproductive technology (ART) has evolved significantly. Over the last 40 years, ART has provided infertile couples with the possibility to conceive, culminating in the birth of over eight million children 1 . IVF protocols are complex and require intensive monitoring, with clinicians and embryologists responsible for several key decision points prior to and during the cycle (Fig. 1 ). Although several of these decisions have a solid evidence base, many are highly subjective and will vary immensely based on clinical experience with an inevitable non-reproducible impact on clinical outcomes—leading to the mantra that ART is an art.

Potential targets for the application of artificial intelligence and machine learning methods during clinical and embryological steps in assisted reproductive technology (ART). Investigations of infertility and pre-treatment counseling are not captured here and discussed independently in Section Pre-treatment counseling. The order and timings of the steps can differ depending on the ART protocol used. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Given these limitations, there is increasing recognition that alternative data-driven approaches that harness the large number of ART cycles undertaken and facilitate objective, consistent, and optimal decision-making may be associated with improved outcomes. Large amounts of data generated during IVF cycles have enabled interdisciplinary researchers to propose artificial intelligence (AI) methodologies to drive individualized approaches. These have ranged from algorithmic drug dosing tools, to ‘human-in-the-loop’ AI clinical decision support systems (CDSSs) for embryo selection, whereby humans are supported by AI but ultimately make the final decision. Harnessing the symbiosis between the experience of clinicians, and personalized recommendations from AI models based on the one million cycles undertaken annually, has the potential to synergistically improve clinical outcomes. In this review, we examine current implementations of AI models within ART, and future prospects concerning their utility, efficacy, and application in the field.

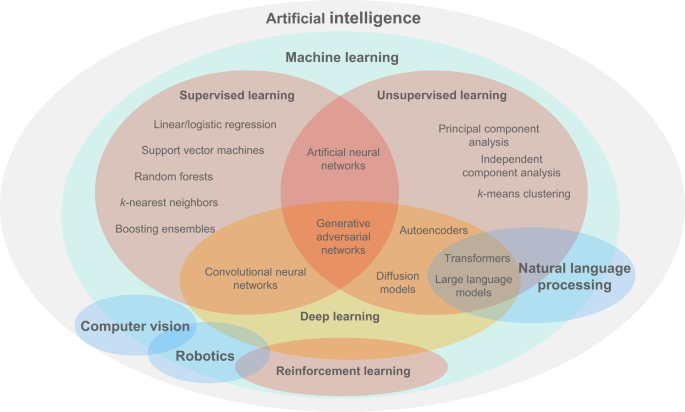

Artificial intelligence methods for assisted reproductive technology

AI is an overarching term that encompasses a growing number of subfields including machine learning (ML), robotics, and computer vision (Fig. 2 ). Principally, ML methods can learn patterns from data and draw inferences, and therefore build models that optimize/personalize ART protocols for a specified outcome. Traditionally, ML can be under either a supervised, unsupervised, or reinforcement learning framework. In supervised learning, data are labeled as inputs and outputs with the goal being to develop models that capture the relationship between the two, which can be used to predict outputs when presented with new, unseen inputs. Conversely, in unsupervised learning, models are built to capture the structure (e.g., clustering) of data with no output labels (‘unlabeled’) that can be used to interpret new, or generate synthetic data. Reinforcement learning trains an ML agent that interacts with a defined environment towards achieving a goal and receives a ‘reward’ for its actions.

A Venn diagram providing a holistic view of the artificial intelligence (AI) landscape, with a particular focus on machine learning (ML) methods. ML is a subfield that is often used in conjunction with other AI subfields, such as computer vision. Some methods can be used in alternative learning frameworks however their most common current manifestations are presented here.

Supervised methods include decision trees, linear/logistic regression, k -nearest neighbors, support vector machines, random forests, artificial neural networks (ANNs), and more. Decision trees are models used to classify or predict outcomes based on input data. They can effectively capture non-linear relationships and can be visualized intuitively as tree-like structures: starting from the root, each branch represents a decision rule to select which subsequent branch should be followed; the final nodes (‘leaves’) of the tree represent outcomes. Extending this to an ‘ensemble’ of trees inspires the random forest algorithm, where each tree is trained on a random partition of the data and its input features. The final prediction is determined by a voting mechanism, combining the predictive power of all decision trees. This generally makes the model less prone to ‘overfitting’, a phenomenon whereby a model may perform very well on training data but poorly on new, unseen data. Supervised methods have widespread applications with tabular (i.e., numerical or categorical) outcomes in ART.

ANNs are networks of connected computational units representing artificial neurons—they receive inputs, process them, and signal the result to other neurons connected to them, in a multi-layered structure (e.g., the multi-layer perceptron algorithm). The input layer receives data to be processed, and the output layer presents the model output. The strengths (‘weights’) of connections between artificial neurons comprise the parameters of the ANN and are calibrated during model training.‘Deep’ learning is ANNs with complex architectures comprising many layers, an example being convolutional neural networks (CNNs), useful for spatial, grid-like data (e.g., embryo images).

As for unsupervised methods, k -means is a popular algorithm for clustering data into k -groups based on the distance of data points from the centroid of each group. Another example is generative adversarial networks (GANs), where one network is trained to generate synthetic data whilst the other discriminates synthetic from real data. The two networks are trained in parallel, competing as adversaries, resulting in better discrimination between synthetic and real data. Multimodal generative AI has recently caught mass media attention, especially through both text (e.g., ChatGPT and Med-PaLM) and text-to-image generators (e.g., DALL-E), which have been evolving rapidly in performance since their inception 2 . These frameworks bring together large language models (LLMs), a type of natural language processing built with ANNs, and diffusion models, an alternative generative methodology to GANs based on iterative de-noising to estimate how image data are distributed to therefore generate a desired image 3 .

During model development, it is standard practice to use ‘training’, ‘validation’, and ‘test’ datasets: ‘training’ to fit the model, ‘validation’ to fine-tune the model’s hyperparameters, and a ‘test’ set to independently evaluate the model’s performance. For generally more reliable estimates of model performance, cross-validation can be used to evaluate the model on multiple training/validation data splits. Using test datasets that are externally unseen and temporally different (e.g., from a different clinic) can provide further reassurance of a model’s generalizability. The fundamental choice of ML algorithm for a certain task is multifaceted and often driven by contextual reasoning. Nevertheless, Table 1 presents some rules-of-thumb regarding popular ML methods (Fig. 2 ) within the context of ART.

Pre-treatment counseling

Classically, age-stratified population estimates have been used to inform patients of their overall chance of success, however, these often fail to incorporate important determinants of outcome such as previous treatment cycle attempts or for treatment-naive patients their ovarian reserve and likely ovarian response. To try to tailor these models further both population data and clinic-specific datasets have been used to develop models for a variety of outcomes including for cumulative live births across multiple cycles 4 . These models are now being used by both patients and a range of stakeholders to manage access to care (national healthcare services, insurance providers) and clinics, or third-party companies offering shared-risk financial programs 5 . Moreover, the emergence of AI chatbots using LLMs could improve efficiency in the initial assessment of infertility. A recent ‘Fast Track to Fertility’ program using semi-automated two-way text messages reduced the time to complete a workup by 50% 6 . The deployment of LLMs for fertility assessment offers unique challenges and currently remains experimental, whilst the frameworks for validation and regulation of such systems are yet to be formalized 2 , 7 .

Gonadotropin dosing for ovarian stimulation

Ovarian stimulation (OS) is used to stimulate the growth of multiple ovarian follicles in order to result in multiple oocytes for retrieval 8 . IVF treatment is a profligate process as not all follicles yield oocytes, not all oocytes will fertilize, and not all embryos will develop, implant, or be capable of becoming healthy babies. Various preparations of gonadotropins exist but most will contain a supra-physiological amount of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) to extend the ‘FSH-window’ by maintaining high FSH levels, and induce multi-follicular growth 9 . Optimization of the gonadotropin dosing regimen can maximize the number of follicles with respect to ovarian potential 9 . As such, an optimal initial dose of FSH can ensure sufficient follicles are recruited, whilst avoiding the recruitment of too many follicles (often defined as >15 oocytes at pickup), and an increased risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) 8 , 10 .

The application of ML approaches to retrospective datasets for model learning has demonstrated the potential to personalize FSH dose as summarized in Table 2 . Fanton et al. aimed to identify the 100 most similar patient profiles to each patient, to then generate individualized dose-response curves 11 . The authors reported limitations including a protocol-agnostic approach, and that 87% of cycles included both pure FSH and Menopur (for luteinizing hormone (LH)-like activity) during OS 11 . The methodology was further evaluated against the national US database (SART CORS) including 365,473 patients and reported upon in conference proceedings 12 . The results similarly predicted that an increased number of two-pronuclear fertilized embryos (2PNs) and blastocysts could be retrieved whilst using significantly lower total FSH doses, key in reducing high medication costs for patients 12 . Nevertheless, OS protocols vary across clinical practice, and the generated dose-response curves presented less confidence in predicting oocytes with lower doses of FSH administration 11 , which are the norm in Europe (where 150-225 IU is suggested for normal responders 8 ). Therefore, it is necessary to determine whether the proposed models are directed at certain geographies or intend to be universal. Setting a precedent for the conduct of future multi-center studies is central to achieving either objective—Ferrand et al. successfully leveraged a federated learning framework 13 , a potentially effective approach that allows data to be kept decentralized and private, whilst deploying ML models for collaborative training between clinics 14 , 15 .

Recent studies have also focused on the effects of demographic, endocrine, and genetic data to optimize OS, and therewith predict the retrieval of mature oocytes 16 , 17 , 18 . Although these are retrospective studies, they highlight the need to explore available characteristics and further assess their impact on clinical outcomes when determining dosing regimens, whereby endocrine monitoring or genomic sequencing for ART cycles may be efficacious for some patients 19 , 20 . To best identify such predictors in an unbiased manner, the treatment cycles of patients should not exist in both the training and test sets 21 . An independent test set of patients should be partitioned at random, or if cross-validation is employed, cycles from the same patient must not exist across the training and test folds.

Ultimately, determining the efficacy of introducing individualized gonadotropin dosing algorithms into the clinic will require appropriate validation across different geographies. The three prospective international multi-center randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for follitropin delta (recombinant-FSH; Ferring Pharmaceuticals) that assess a unique algorithm to facilitate individualization of dose based on anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and body weight are an apt example of that critical step 22 , 23 , 24 . The retrospective studies in Table 2 would benefit from similar prospective validation in multiple centers to establish whether their adoption in the clinic is appropriate and of value for patients.

Induction of oocyte maturation

Once multiple follicles have grown during OS, a hormonal trigger is administered to mature oocytes in preparation for retrieval. The triggering agent is most efficacious when follicles are neither too large nor too small 10 . In turn, AI/ML techniques have been harnessed to optimize the trigger day (TD) as summarized in Table 3 . Our research team previously developed a random forest model to determine follicle sizes on TD that most contributed to the number of mature oocytes retrieved 25 . Maximizing the number of follicles sized 12-19 mm on TD was determined as optimal for yielding mature oocytes and could be used as a feature in conjunction with baseline endocrine characteristics to predict oocyte yield 19 .

A more recent study leveraged patients that had ultrasound scans both on the day before trigger, and on the true TD, to learn why a clinician might decide to wait a further day to trigger 26 . They found follicles sized 16-20 mm as most contributory in determining optimal TD, and predicted superior outcomes in terms of 2PN and blastocyst yield compared solely to a clinician’s decision 26 . With a similar methodology but using a simpler model, Fanton et al. confirmed the findings with even further granularity and showed follicles sized 14-15 mm were most predictive on TD, whilst those sized 11-13 mm on the day prior to triggering were most contributory 27 . The aforementioned studies employed ML methods which show predictor importance measures against the desired outcome (oocytes retrieved), and therefore provide a useful data-driven target for oocyte maturation based upon many previous IVF cycles 25 , 26 , 27 . Transparent models such as these should be favored at embryonic stages of AI-driven developments, to ensure clinicians and patients can gain trust towards CDSSs as part of ART workflows 28 , 29 . It is crucial to take into account the nuances of workload management in daily clinical practice in order to incorporate AI models into workflows effectively 30 . Real-world data where ultrasound scans may not be conducted every day can challenge the precision of models developed to assess TD or misrepresent the predictive capacity of certain features.

A proof-of-concept CDSS by Letterie and MacDonald (Table 2) also considered a decision point to trigger or cancel the cycle 30 . This notion was further developed in a later study looking specifically at TD assignment to optimize the retrieval of oocytes 31 . Features included pre-cycle characteristics, as well as estradiol level and follicle diameters determined on the single ‘best day’ for assessing TD, for which baseline AMH alone was most predictive 31 . A stacking model was trained, which compounds the predictive power of multiple ML models to improve overall robustness. This CDSS fulfills the need for streamlining follicular monitoring that may arise from reasons such as long-distance travel to clinics or unprecedented public health constraints. In response to the constraints enforced by COVID-19, Roberston et al. demonstrated that day-5 of OS would be the ‘best day’ for predicting both the risk of OHSS and optimal TD 32 . Both these studies highlight reducing monitoring in certain clinical settings may be possible, which could reduce resource requirements in the clinic, and the burden upon patients. The timing of the TD is a multifaceted decision point and therefore to confirm utility in practice, prospective validation of the developed models in diverse populations would be a prudent next step forward.

In the embryology laboratory

The application of AI in the embryology lab has attracted significant recognition in recent years and has been reviewed comprehensively 33 , 34 , with more recent developments summarized here (Tables 4 , 5 , and 6 ). The capacity of AI techniques to analyze large amounts of complex data such as images and time-lapse objectively, whereby non-invasive assessment of gametes and embryos can be done in real-time, has significant potential for future impact in achieving healthy live birth. This can lessen the need for specialist embryology resources whilst automating some of the processes involved to reduce costs.

Sperm assessment

Computer-aided sperm analysis.

Standard semen analysis comprising of concentration, motility, and morphology assessment remains the first-line investigation of pre-treatment male fertility potential. Computer-aided sperm analyzers (CASA) aim to reduce intra-operator subjectivity and variability associated with manual assessment while standardizing and increasing throughput capacity. CASA analysis of sperm concentration and motility have shown a good correlation with manual assessment 35 , while estimates of progressive motility are also significantly linked to both in vivo and in vitro fertilization rates 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 . However, CASA-based morphological assessment tends to correlate the least with manual assessment, likely as a result of heterogeneity within a given semen sample and the subjective nature of interpretation 35 .

The latest WHO manual on sperm analysis 40 (2021) recognized the ability of CASA to accurately determine sperm concentration and progressive motility parameters through the use of fluorescent DNA stains and tail-detection algorithms 41 . These advancements have improved the distinction between immotile spermatozoa and particulate debris; a problem that has led to the overestimation of concentration, and underestimation of progressive motility, since the inception of computer-aided systems.

At a population level, ML algorithms could be a useful to identify individuals at risk of an abnormal semen profile. An ANN based on an 11-question demographic characteristic questionnaire (including age, alcohol consumption, smoking status, urbanization and occupational exposures) achieved 92.9% accuracy in predicting abnormal sperm concentration, and 85.7% for predicting any sperm abnormality 42 . Although only developed in a small cohort of 141 men, if replicated, an AI-driven triage model could be used as a preliminary screening tool with early recourse to diagnostic testing.

Further, an ANN using semen parameters as inputs in 177 men was able to predict seminal plasma biochemical markers including fructose, zinc, and total protein content 43 . The added value of these biochemical parameters over standard semen analyses is still unclear, but a number of omics-based markers in seminal fluid have been identified as helpful in determining fertilization prognosis in a cost-effective manner 44 . Incorporating these techniques into the IVF clinic is challenging, namely due to initial set up costs and specialized techniques required for analysis. Moreover, whether these markers and profiles could drive selection of an individual spermatozoon for fertilization remains unclear.

Accurate assessment of sperm motility is paramount in fully understanding genetic and biochemical factors that may impact normal fertilization and thus plays a key role in selection for ART. Motility prediction based on deep learning using sperm videos has been examined with promising results 45 , 46 , 47 . AI software may begin to allow correlation of kinetic motility patterns with other crucial factors such as sperm morphology, likelihood of fertilization, or blastocyst formation to aid in selection for intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) in real-time 48 , 49 . These studies show the potential of incorporating temporal features into deep learning models to extract insights into sperm motility consistently and efficiently.

Staining of spermatozoa is currently required to identify morphological abnormalities and defects for diagnostic purposes. However, given that the staining of sperm affects their vitality and motility, tested spermatozoa are no longer viable for use in ICSI and thus, do not aid in sperm selection for fertilization 50 . Consequently, morphological assessment of a single spermatozoon in a non-invasive manner using AI techniques is of interest for sperm selection 34 . Some models consider specifically the sperm head morphology 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , whereas others consider a more comprehensive analysis of the whole sperm 55 .

WHO describe eleven different sperm head abnormalities by taking into account shape, size, and consistency 40 . Some of these subtypes present further challenges, with their morphology forming a vast continuum with overlaps, such that discrimination is complex to the naked eye. Using a dictionary learning approach combined with segmented microscopic sperm head images, Shaker et al. achieved a 92.3% accuracy in distinguishing between four sub-types against a ground truth dataset agreed by three experts 52 .

Open datasets of spermatozoa are becoming accessible to researchers and have been used to benchmark different models against one another 51 , 52 , 56 . Latest deep learning advancements with CNNs are capable of detecting morphological deformities in spermatozoa head, acrosome, and vacuole in real-time using low-magnification microscopes (400-600x) without staining and with increased objectivity 56 , 57 .

Non-invasive AI methods are also capable of assessing morphological features of immotile or frozen sperm that are difficult to characterize manually. Current viability tests require cytotoxic staining that renders individual spermatozoon unusable for ICSI. Recently, Jiang et al. described an AI model capable of identifying viable sperm based on a single bright-field image without the need for any sample processing or reagents 58 . The model exhibited 94.9% accuracy, 97.0% sensitivity, and 93.3% specificity, based on subtle morphological changes to the cell nucleus. Incorporation of such AI models into existing CASA systems could further reduce the need for sperm staining in the future, especially in the context of surgically retrieved or frozen sperm with unknown viability.

To our knowledge, no computer-aided systems exist to improve the surgical retrieval of sperm yet. Current testicular sperm extraction techniques for ICSI can be challenging, with outcomes being greatly operator-dependent 59 . However, AI techniques to aid identification of sperm from biopsies during testicular sperm extraction have been investigated. Wu et al. describe a deep CNN capable of finding sperm in testicular biopsy samples with good accuracy (mean average precision of 0.74) but did not compare this to standard embryology techniques 60 . ML models employing 16 preoperative assessment variables (e.g., hormonal parameters, genetic, demographic, lifestyle, and urogenital history) have also been shown with moderate performance to predict the success of testicular sperm extraction 61 . Given the clinical implications of not pursuing surgical sperm retrieval (i.e., unequivocal use of donor sperm), further external validation of this promising model is required. The inclusion of additional biomarkers such as more detailed genetic information, seminal plasma microRNA, or additional hormones, as a way of further improving model performance, would also be of interest.

Sperm selection for ICSI is not standardized and WHO guidelines are interpreted subjectively by embryologists. High-throughput AI models have the potential to be more objective and tackle the fundamental challenge of selecting individual sperm with the best potential for embryo formation from a sample of over 10 8 gametes 50 . Nonetheless, with respect to morphology, there are currently no studies that assess AI performance against manual assessment according to WHO guidelines 34 . Indeed, the potential performance of AI networks is directly linked to the quality of the database used for training, as well as the caliber of data used as input. Progress on its use in sperm selection would benefit from global collaboration between clinical and laboratory teams to build a robust and definitive database of sperm images to establish a consensus ground truth.

DNA fragmentation

Existing techniques for sperm DNA fragmentation similarly lack data at the single spermatozoon level. Modern-day tests of DNA integrity are invasive and conducted at the sample level, making them an unsuitable metric in the selection of individual sperm for ICSI. McCallum et al. described a CNN trained using a set of 1064 images of individual sperm cells of known DNA integrity to provide a DNA integrity prediction from a single bright-field image in under 10 ms 62 . Recently, Kuroda et al. described further progress with their AI-augmented sperm chromatin dispersion (SCD) test kit capable of assessing DNA fragmentation in >5000 spermatozoa at once, compared to a limited 300 in the widely commercially-used Halosperm SCD test 63 . The improved kit showed a good correlation with the conventional test that requires manual counting (Halosperm G2; r = 0.69, p = 0.02). DNA fragmentation counting took 5 min. in the automated device compared to around 20 min. with the manual method 63 .

Emerging evidence increasingly suggests that sperm DNA fragmentation is associated with reduced male reproductive capability and can be assessed in combination with conventional sperm analysis 64 . However, routine testing remains contentious and may not necessarily provide predictive value 65 . Other technical limitations exist, in particular the use of different staining, microscopes, and assays for DNA fragmentation that can challenge the training of an accurate AI model. Guidelines for testing, and optimal techniques for testing sperm DNA fragmentation have been proposed 66 , 67 , but testing is still not widely recommended. Progress in this field thus relies on the standardization and optimization of DNA fragmentation assays, prospective evaluation of its impact on ART outcomes, and the development of therapies to improve sperm DNA fragmentation levels 68 . Should this be achieved, ML algorithms that can combine morphological, motility, and DNA fragmentation data with outcomes such as fertilization, miscarriage, and live birth rates, could standardize, and vastly improve, single sperm assessment/selection by reducing the subjective and inter-variable outcomes between embryologists.

Oocyte assessment

Nuclear maturity of human oocytes can only be verified by observation of the extruded polar body, which requires removal of the cumulus 10 . Automated, non-invasive methods to assess nuclear and cytoplasmic maturity and future reproductive potential would be desirable, particularly for fertility preservation. Accurate prediction of oocyte quality and fertilization prospects would allow better estimation of personalized live birth predictions from a pool of cryopreserved oocytes. Consideration of whether this is sufficient to realize a desired family size may dictate the need for further cycles of OS and cryopreservation. Clinicians would also be able to manage expectations for success and reduce the number of poor-quality embryos with low implantation potential 69 .

Currently, assessment of nuclear oocyte maturity is performed visually by embryologists in a subjective manner prior to fertilization. Oocyte scoring systems assessing cytoplasmic morphological features such as the presence of vacuoles, degree of perivitelline space, and cytoplasmic granularity, among others, have long been proposed as predictors of insemination outcome but remain points of contention as prognostic indicators of embryo development and implantation 70 , 71 . Substantial labeled datasets of oocytes are scarce—as such, Kanakasabapathy et al. combined a retrospective dataset of oocyte images with known fertilization outcomes alongside synthetic oocyte images generated by a GAN to form a synthetic CNN 72 . This synthetically-extended CNN outperformed the raw CNN, and delivered an accuracy of 82.58% with an AUC of 0.81 in identifying oocytes that would fertilize normally to form two-pronuclear zygotes (2PNs), versus those that would not (non-2PNs) 72 . This study showed the value of using AI to augment the training, predictive power, and robustness of existing CNNs available for the embryology lab, perhaps widening their scope of use in ART 73 .

A non-invasive CNN-based software, VIOLET™ (Future Fertility), has been shown to predict fertilization and blastulation with 91.2% and 63% accuracy respectively, based on morphological features of 2D oocyte images. The tool’s performance was much quicker and also outperformed expert embryologists in accuracy 74 . VIOLET™ aims to give users undergoing oocyte cryopreservation a personalized estimate of live birth potential based on the morphology of oocytes cryopreserved as opposed to generalized age-related outcomes. Similarly, the MAGENTA™ tool employs 2D images of denuded oocytes and a similar morphology-based CNN to score oocytes and predict the potential for high-quality blastocyst formation with good accuracy 75 . Though promising in correlating oocyte morphology with blastocyst potential, their estimates lack interplay with potential male factor subfertility and could benefit from the incorporation of clinical variables such as BMI or endometriosis, to enhance the prediction of outcomes such as clinical pregnancy or live birth.

More recently, a non-invasive gene expression test was prospectively trialed by Link et al. 76 . The ‘OsteraTest’ software is composed of eight ML modules and uses a 25-gene network to predict oocyte quality based on cumulus cells 76 . This bioinformatics-inspired approach was able to non-invasively predict oocyte development to a day-5 blastocyst with 86% accuracy 76 . Though further large-scale validation is necessary, this type of AI approach could change current practices in oocyte selection prior to cryopreservation and ICSI, as well as reduce the pool of embryos formed, cryopreserved, and tested, prior to embryo transfer. This may be particularly beneficial in countries with regulatory frameworks surrounding embryos such as Poland, where only six oocytes may be fertilized per cycle, or Germany where no more than three embryos can be stored per treatment attempt. Additionally, it may guide egg sharing or donor oocyte cycles and inform on how to distribute oocytes evenly or the total within a cohort depending on blastocyst potential.

Although these approaches provide direction for further research, the data must be viewed with caution until published in peer-reviewed journals. In developing an AI model, it is imperative to define a set end goal such as oocyte quality following oocyte cryopreservation. If fertilization is planned and blastocyst potential is being predicted, then spermatozoon quality and other male confounders should be considered. Proposed biomarkers to predict oocyte potential include follicular fluid markers (insulin-like growth factor, zinc levels 77 ), cumulus-oocyte complex composition 78 , and cytoplasmic features like mitochondrial function 79 . Consideration of these methods to guide oocyte selection in the future would also require analysis into whether they are feasible in daily practice or in fact as cost-effective as fertilizing all suitable oocytes 80 .

Embryo assessment

Embryo selection based on morphological assessment is an important predictor of success in IVF cycles but is primarily based on static visual observations at specific developmental time points. Information obtained in this manner is not only highly subjective with great inter-operator variability but also diminishes the dynamic nature of a developing embryo in culture, thus limiting its accuracy. AI-driven embryo analysis is suited to predicting developmental potential, non-invasive aneuploidy assessment, and ultimately the selection of an embryo with the best live birth potential for transfer.

Morphokinetics and morphology

Examples of developments in embryo evaluation include the assessment of pronuclear stage embryos to differentiate between 2PN and non-2PN zygotes 81 , 82 . Morphokinetic data such as cytoplasmic movements have also shown potential to predict blastocyst formation at early cleavage stages in a time series-based ANN model 83 . Further assessments of interest include morphological classification of pronuclei size and arrangement to monitor embryo development 84 . CNN models showed comparable results to manual labeling, albeit with high precision and reproducibility at a fraction of the time required by clinicians (12.18 s vs. 130 hrs.) 84 . Despite promising results, the standard morphological assessment remains the international consensus which is subjective and labor-intensive.

Time-lapse images combined with automated morphology assessment of embryos based on CNNs have shown promise, capable of outperforming individual embryologists with excellent accuracy 85 , 86 . Other fully automated deep learning-based models using time-lapse images such as iDAScore (Vitrolife) have shown the ability to accurately assess embryo morphology without the need for concurrent embryologist assessment or annotation, and predict implantation outcome 87 , 88 , 89 . The benefit of using time-lapse incubation systems and/or AI technology in the embryo selection process is yet to be proven as superior to current means in double-blind RCTs 90 , 91 . The SelecTIMO trial recently showed no improvement in cumulative live birth rates when using uninterrupted culture conditions with routine morphological embryo selection compared to a time-lapse based embryo selection algorithm alongside uninterrupted culture for day-3 embryos 92 . With no improvement in cumulative pregnancy rates or time-to-pregnancy, it may be that the time-lapse selection method may not improve pregnancy rates, however, whether this applies to day-5 embryos is still to be clarified. Nevertheless, the time-lapse technology was not inferior and therefore could achieve similar outcomes in an automated and less subjective manner. Importantly, with modern advancements in cryopreservation, it is likely that the most viable embryos will eventually be transferred if needed. Additionally, human input may be needed to aid the assessment of embryo quality, for example, by repositioning embryos to get a better view, which should be taken into account when considering the application of an AI for this task. Validation data from the VISA Study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04969822), a noninferiority, prospective, multi-center RCT may further reflect the clinical impact of AI-driven systems compared to manual morphology assessment by embryologists for day-5 embryos. Such studies highlight the necessity for the accuracy of predictions made via AI techniques to be prospectively validated prior to adoption into clinical practice with appropriate mitigation of study biases and evaluation of cost-effectiveness 20 , 93 .

Recently, a biomarker-scoring CDSS based on 799 blastocyst videos, CHLOE EQ ™ (Fairtility), has been described and takes into account patient and embryo data including blastocyst diameter, degree, and time of expansion, and other morphokinetic markers. Though preliminary results are promising, these new systems still require external validation and larger-scale prospective studies before widespread adoption to realize the end goal of fully automated blastocyst assessment and accurate embryo prognosis 94 , 95 . It is paramount that future algorithms focus not only on the competitive selection of the best embryos for culture and transfer but also can differentiate between embryos that are otherwise morphologically indistinguishable to the naked eye, wherein the real challenge lies.

Rates of pre-implantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) as a screening tool to improve clinical outcomes in ART cycles have increased in recent years. Currently, PGT-A is performed by trophectoderm biopsy on blastocysts followed by whole-genome or targeted DNA amplification and a next-generation sequencing assay. Multiple blinded non-selection studies have now shown a high prognostic failure of live birth when an aneuploid result is obtained 96 , 97 . Furthermore, discarding uniformly aneuploid embryos is unlikely to have a meaningful impact on cumulative live birth rates, especially in women over 35 years of age where it is more likely to be employed 98 . As modern invasive techniques still bring technical and financial challenges, non-invasive AI-driven PGT-A could offer the benefits of PGT-A without embryo manipulation and biopsy. Recent single-center studies have shown ongoing validation of AI models feeding time-lapse imaging data into CNNs to predict ploidy status from abnormal morphokinetic patterns with good accuracy 99 , 100 . These models may not replace PGT-A but highlight the potential for PGT-A triage and well-informed guidance towards embryo selection in a non-invasive manner 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 . Once again, further validation and large multi-center datasets must be compiled for standardization and generalization of these AI-driven models.

A comprehensive understanding of the embryo at a molecular level may present another adjunct for the high throughput and comprehensive capabilities of AI-driven predictive models in the future. Various metabolomic signatures of an embryo have been investigated over the years, mainly pertaining to metabolites or biomarkers in spent culture media as a reflection of complex physiological and pathological responses and in turn, reproductive potential or ploidy status. Conflicting results to this approach have been shown 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , while a previous meta-analysis including four RCTs and a total of 924 women showed no meaningful effects for metabolomic assessment on clinical outcomes 108 . Interestingly, an ANN employing a combination of conventional embryological data and thirteen nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy-identified metabolite levels has shown promise in predicting blastocyst implantation, though at a very small scale with a test dataset of twelve spent culture media 109 .

Current limitations of the omics approach lie within the vast variability in culture media components used and handling of spent media, contrasting infertility phenotypes, definitive biomarkers predictive of reproductive potential, and a general lack of conclusive evidence that fertility outcomes can be optimized through omics profiling. Though non-invasive, highly specific, and perhaps crucial towards a better understanding of gamete development, it is unclear whether omics profiling can effectively contribute to an improvement in clinical outcomes or will remain principally a research tool 110 . Furthermore, the complexities of omics analysis and interpretation of output data present significant barriers to adoption in daily laboratory practice.

Embryo quality aside, reproductive outcomes also depend on implantation and the endometrium. The construction of models should also integrate features of the uterus and crosstalk between an embryo and the endometrium. To date, the clinical benefit of an endometrial receptivity array (ERA) for assessment has yet to be proven 111 . The invasive nature of biopsy for endometrial receptivity testing, the time needed for results preventing immediate embryo transfer, and the potential accuracy of the diagnostic test itself are further limitations 112 . AI is however well suited to drive collaboration between ART clinics and omics-focused research groups, on account of its ability to perform large-scale data throughput and analysis. Whether these approaches will alter conventional therapies remains unclear, particularly as diagnoses such as true recurrent implantation failure and its relevance are being hotly debated currently 113 . However, given the lessons to date, the value of any ‘AI-omics’ platform should be validated in appropriately powered RCTs.

Conclusions and future prospects

With respect to ART, several groups have developed CDSS frameworks or decision-making tools for use at key decision-points in the clinic, and/or embryology laboratory 17 , 30 , 31 . Personalization in further avenues could better improve the clinical outcomes of ART. Ovarian response has been shown to vary significantly depending on ovarian reserve, between ethnic groups 114 , 115 , FSH receptor genetic polymorphisms 116 , and body weight 19 , 117 . Therefore, incorporating such factors which influence pharmacokinetic parameters when dosing gonadotropins 9 , 19 , 20 , or suppressing premature ovulation 20 , 118 , may be beneficial. ML methods could also help tailor luteal phase support regimens to certain patient subgroups, where a lack of clinical consensus currently exists 119 .

The ubiquity of electronic health records (EHRs) has accelerated the development of CDSSs 15 . A predominant barrier to adoption is trustworthiness, especially with ‘black-box’ AI systems 29 , which has led to transparency being a key characteristic preferred by clinicians as such models offer simpler interpretations, although may compromise accuracy when applied to more complicated learning tasks 28 . Implementations of ‘black-box’ models are evolving, especially for embryological analyses, due to the data being primarily image-based; in turn, efforts in explainability have emerged to seek insights for model generalizability, fairness, and trustworthiness 94 , 95 . Misleading conclusions may be reached if clinical inference is neglected during the decision-making process since such methods are often correlation-based and prone to ‘overfitting’ 120 . Generating counterfactual examples in this context, such as: “what if the optimal TD was yesterday(?)", or “what if the other embryo were implanted(?)", are generally unavailable—and to further exacerbate this—ground truths are often based upon clinical guidelines/scoring rather than objective outcome labels. The emergence of omics analyses offers an alternative, and arguably more efficient, solution for clinical and embryological assessment, although advancements currently remain of a preliminary nature 18 , 108 . Ultimately, appropriate assessment of CDSSs for ART is necessary in practical, ethical, and clinical contexts prior to clinical adoption. Rigorous validation with comprehensive standardized reporting is essential for establishing trustworthy models before attempting viable integration into clinical workflows 21 , 121 . Research conduct and reporting guidelines such as PROBAST-AI are in progress for the wider field of AI for healthcare, and with this at hand, a more granular and contextual guideline for AI in the domain of ART can be proposed 122 , 123 .

Salient efforts from both academia and industry have validated the utility of retrospective data to enable data-driven decision-making for ART 123 . To ensure viable deployment, these models can benefit from larger, multi-center datasets that incorporate both heterogeneous patient populations and also capture the idiosyncratic nature of clinical practice worldwide. Achieving this is best achieved through a collaborative effort from all stakeholders representing multiple disciplines across the AI and healthcare landscape 21 . Furthermore, streamlining workloads is an essential objective of CDSSs, and seamless implementation with, or within, EHR systems are essential to not inadvertently decrease the efficiency of clinical workflows. Prospective validation (e.g., well-designed RCTs) with relevant outcome measures is a key step to assess the efficacy and efficiency of these models in clinical environments and thus demonstrate impact on patient outcomes. With such efforts in place, a comprehensive end-to-end CDSS seems a plausible future goal. Whether this paradigm should extend to an autonomous AI clinician within the ART domain remains an open and contentious question. The use of AI to automate some of the tasks currently performed by clinicians or laboratory staff could have implications in training and a potential loss of expertise in the workforce, but may also free up staff time to focus on more challenging and physically demanding technical processes. Reflections on the current literature to date elicit valuable questions regarding future studies, including determining the specification of what should be measured/captured, to what precision, and how often. Decision points cannot necessarily be considered in isolation, and the relationships between some of the key topics described in this review require further interdisciplinary research to prioritize the individualization and utility of certain decisions over others. The intersection of AI and ART undoubtedly remains a nascent and valuable field of study, which has the potential to reduce intensive resources, whilst ultimately improving clinical outcomes for patients.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Fauser, B. C. Towards the global coverage of a unified registry of IVF outcomes. Reprod. Biomed. Online 38 , 133–137 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Thirunavukarasu, A. J. et al. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 29 , 1930–1940 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Gu, S. et al. Vector quantized diffusion model for text-to-image synthesis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 10696–10706 (IEEE, 2022).

McLernon, D. J. & Bhattacharya, S. Quality of clinical prediction models in in vitro fertilisation: which covariates are really important to predict cumulative live birth and which models are best? Pract. Res. Clin. Obstetr. Gynaecol. 135 , 102309–102329 (2022).

Jenkins, J. et al. Empathetic application of machine learning may address appropriate utilization of ART. Reprod. BioMed. Online 41 , 573–577 (2020).

Senapati, S. et al. The fast track to fertility program: rapid cycle innovation to redesign fertility care. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 3 , CAT–22 (2022).

Google Scholar

Mesko, B. & Topol, E. J. The imperative for regulatory oversight of large language models (or generative AI) in healthcare. NPJ Digi. Med. 6 , 120 (2023).

Article Google Scholar

Broekmans, F. J. Individualization of FSH doses in assisted reproduction: facts and fiction. Front. Endocrinol. 10 , 181 (2019).

Abbara, A. et al. FSH requirements for follicle growth during controlled ovarian stimulation. Front. Endocrinol. 10 , 579 (2019).

Abbara, A., Clarke, S. A. & Dhillo, W. S. Novel concepts for inducing final oocyte maturation in in vitro fertilization treatment. Endocr. Rev. 39 , 593–628 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fanton, M. et al. An interpretable machine learning model for individualized gonadotropin starting dose selection during ovarian stimulation. Reprod. BioMed. Online https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2022.07.010 (2022).

Fanton, M., Baker, V. L. & Loewke, K. E. Selection of optimal gonadotropin dose using machine learning may be associated with improved outcomes and reduced utilization of FSH. Fertil. Steril. 118 , e80–e81 (2022).

Ferrand, T. et al. Predicting the number of oocytes retrieved from controlled ovarian hyperstimulation with machine learning. Hum. Reprod. 38 , 1918–1926 (2023).

Nguyen, T. et al. A novel decentralized federated learning approach to train on globally distributed, poor quality, and protected private medical data. Sci. Rep. 12 , 1–12 (2022).

Heinis, T. & Ailamaki, A. Data Infrastructure for Medical Research 2nd edn, Vol. 4 (Now Publishers, 2017).

Correa, N., Cerquides, J., Arcos, J. L. & Vassena, R. Supporting first FSH dosage for ovarian stimulation with machine learning. Reprod. BioMed. Online 45 , 1039–1045 (2022).

Xu, H. et al. POvaStim: An online tool for directing individualized FSH doses in ovarian stimulation. Innovation 4 , 100401 (2023).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zieliński, K. et al. Personalized prediction of the secondary oocytes number after ovarian stimulation: A machine learning model based on clinical and genetic data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 19 , e1011020 (2023).

Abbara, A. et al. Endocrine requirements for oocyte maturation following hCG, GnRH agonist, and kisspeptin during IVF treatment. Front. Endocrinol. 764 , 412999 (2020).

Voliotis, M. et al. Quantitative approaches in clinical reproductive endocrinology. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metabol. Res. 88 , 100421 (2022).

Wiens, J. et al. Do no harm: a roadmap for responsible machine learning for health care. Nat. Med. 25 , 1337–1340 (2019).

Andersen, A. N. et al. Individualized versus conventional ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, assessor-blinded, phase 3 noninferiority trial. Fertil. Steril. 107 , 387–396 (2017).

Ishihara, O. & Arce, J.-C. et al. Individualized follitropin delta dosing reduces OHSS risk in Japanese IVF/ICSI patients: a randomized controlled trial. Reprod. Biomed. Online 42 , 909–918 (2021).

Qiao, J. et al. A randomised controlled trial to clinically validate follitropin delta in its individualised dosing regimen for ovarian stimulation in asian IVF/ICSI patients. Hum. Reprod. 36 , 2452–2462 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Abbara, A. et al. Follicle size on day of trigger most likely to yield a mature oocyte. Front. Endocrinol. 9 , 193 (2018).

Hariton, E. et al. A machine learning algorithm can optimize the day of trigger to improve in vitro fertilization outcomes. Fertil. Steril. 116 , 1227–1235 (2021).

Fanton, M. et al. An interpretable machine learning model for predicting the optimal day of trigger during ovarian stimulation. Fertil. Steril. 118 , 101–108 (2022).

Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1 , 206–215 (2019).

Afnan, M. A. M. et al. Interpretable, not black-box, artificial intelligence should be used for embryo selection. Hum. Reprod. Open (2021).

Letterie, G. & Mac Donald, A. Artificial intelligence in in vitro fertilization: a computer decision support system for day-to-day management of ovarian stimulation during in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 114 , 1026–1031 (2020).

Letterie, G., MacDonald, A. & Shi, Z. An artificial intelligence platform to optimize workflow during ovarian stimulation and IVF: process improvement and outcome-based predictions. Reprod. BioMed. Online 44 , 254–260 (2022).

Robertson, I., Chmiel, F. & Cheong, Y. Streamlining follicular monitoring during controlled ovarian stimulation: a data-driven approach to efficient IVF care in the new era of social distancing. Hum. Reprod. 36 , 99–106 (2021).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dimitriadis, I., Zaninovic, N., Badiola, A. C. & Bormann, C. L. Artificial intelligence in the embryology laboratory: a review. Reprod. BioMed. Online (2021).

Riegler, M. A. et al. Artificial intelligence in the fertility clinic: status, pitfalls and possibilities. Hum. Reprod. 36 , 2429–2442 (2021).

Finelli, R., Leisegang, K., Tumallapalli, S., Henkel, R. & Agarwal, A. The validity and reliability of computer-aided semen analyzers in performing semen analysis: a systematic review. Transl. Androl. Urol. 10 , 3069–3079 (2021).

Dearing, C., Jayasena, C. & Lindsay, K. Can the sperm class analyser (SCA) CASA-Mot system for human sperm motility analysis reduce imprecision and operator subjectivity and improve semen analysis? Hum. Fertil. (2019).

Shibahara, H. et al. Prediction of pregnancy by intrauterine insemination using CASA estimates and strict criteria in patients with male factor infertility. Int. J. Androl. 27 , 63–68 (2004).

Garrett, C., Liu, D., Clarke, G., Rushford, D. & Baker, H. Automated semen analysis: ‘zona pellucida preferred’ sperm morphometry and straight line velocity are related to pregnancy rate in subfertile couples. Hum. Reprod. 18 , 1643–1649 (2003).

Larsen, L. et al. Computer-assisted semen analysis parameters as predictors for fertility of men from the general population. Hum. Reprod. 15 , 1562–1567 (2000).

Organization, W. H. et al. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen 6th edn, Vol. 2 (World Health Organization, 2021).

Gallagher, M. T., Cupples, G., Ooi, E. H., Kirkman-Brown, J. C. & Smith, D. J. Rapid sperm capture: high-throughput flagellar waveform analysis. Hum. Reprod. 34 , 1173–1185 (2019).

Badura, A. et al. Prediction of semen quality using artificial neural network. J. Appl. Biomed. 17 , 167–174 (2019).

Vickram, A. S. et al. Validation of artificial neural network models for predicting biochemical markers associated with male infertility. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 62 , 258–265 (2016).

Llavanera, M., Delgado-Bermúdez, A., Ribas-Maynou, J., Salas-Huetos, A. & Yeste, M. A systematic review identifying fertility biomarkers in semen: a clinical approach through omics to diagnose male infertility. Fertil. Steril. 118 , 291–313 (2022).

Hicks, S. A. et al. Machine learning-based analysis of sperm videos and participant data for male fertility prediction. Sci. Rep. 9 , 16770 (2019).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Thambawita, V., Halvorsen, P., Hammer, H., Riegler, M. & Haugen, T. B. Extracting temporal features into a spatial domain using autoencoders for sperm video analysis. arXiv (2019).

Ottl, S., Amiriparian, S., Gerczuk, M. & Schuller, B. W. motilitAI: A machine learning framework for automatic prediction of human sperm motility. iScience 25 , 104644 (2022).

Saiffe Farías, A. F. et al. Single-sperm motility analysis during ICSI using an artificial intelligence sperm identification software (SID) and correlation with morphology. Fertil. Steril. 118 , e56–e57 (2022).

Mendizabal-Ruiz, G. et al. Computer software (SID) assisted real-time single sperm selection associated with fertilization and blastocyst formation. Reprod. BioMed. Online 45 , 703–711 (2022).

You, J. B. et al. Machine learning for sperm selection. Nat. Rev. Urol. 18 , 387–403 (2021).

Chang, V., Garcia, A., Hitschfeld, N. & Härtel, S. Gold-standard for computer-assisted morphological sperm analysis. Comput. Biol. Med. 83 , 143–150 (2017).

Shaker, F., Monadjemi, S. A., Alirezaie, J. & Naghsh-Nilchi, A. R. A dictionary learning approach for human sperm heads classification. Comput. Biol. Med. 91 , 181–190 (2017).

Riordon, J., McCallum, C. & Sinton, D. Deep learning for the classification of human sperm. Comput. Biol. Med. 111 , 103342 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Improving human sperm head morphology classification with unsupervised anatomical feature distillation. In 2022 IEEE 19th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) 01–05 (IEEE, 2022).

Movahed, R. A., Mohammadi, E. & Orooji, M. Automatic segmentation of sperm’s parts in microscopic images of human semen smears using concatenated learning approaches. Comput. Biol. Med. 109 , 242–253 (2019).

Javadi, S. & Mirroshandel, S. A. A novel deep learning method for automatic assessment of human sperm images. Comput. Biol. Med. 109 , 182–194 (2019).

Abbasi, A., Miahi, E. & Mirroshandel, S. A. Effect of deep transfer and multi-task learning on sperm abnormality detection. Comput. Biol. Med. 128 , 104121 (2021).

Jiang, A., Jiaqi, W., Zhao, H., Zhang, Z. & Sun, Y. Identifying viability of immotile sperm at one glance: Sperm viability classifier powered by deep learning. Fertil. Steril. 118 , e297–e298 (2022).

Kresch, E., Efimenko, I., Gonzalez, D., Rizk, P. J. & Ramasamy, R. Novel methods to enhance surgical sperm retrieval: a systematic review. Arab J. Urol. 19 , 227–237 (2021).

Wu, D. J., Badamjav, O., Reddy, V. V., Eisenberg, M. & Behr, B. A preliminary study of sperm identification in microdissection testicular sperm extraction samples with deep convolutional neural networks. Asian J. Androl. 23 , 135–139 (2021).

Bachelot, G. et al. A machine learning approach for the prediction of testicular sperm extraction in nonobstructive azoospermia: algorithm development and validation study. J. Med. Inter. Res. 25 , e44047 (2023).

McCallum, C. et al. Deep learning-based selection of human sperm with high DNA integrity. Commun. Biol. 2 , 250 (2019).

Kuroda, S. et al. Development of a novel robust artificial intelligence developed sperm DNA fragmentation test—preliminary findings. Fertil. Steril. 118 , e307 (2022).

Peng, T. et al. Machine learning-based clustering to identify the combined effect of the DNA fragmentation index and conventional semen parameters on in vitro fertilization outcomes. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 21 , 26 (2023).

Cissen, M. et al. Measuring sperm DNA fragmentation and clinical outcomes of medically assisted reproduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 11 , e0165125 (2016).

Agarwal, A. et al. Sperm DNA fragmentation: a new guideline for clinicians. World J. Mens Health 38 , 412–471 (2020).

Esteves, S. C. et al. Sperm DNA fragmentation testing: summary evidence and clinical practice recommendations. Andrologia 53 , e13874 (2021).

Alahmar, A. T., Singh, R. & Palani, A. Sperm DNA fragmentation in reproductive medicine: a review. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 15 , 206–218 (2022).

Zaninovic, N. & Rosenwaks, Z. Artificial intelligence in human in vitro fertilization and embryology. Fertil. Steril. 114 , 914–920 (2020).

Rienzi, L. et al. Significance of metaphase ii human oocyte morphology on ICSI outcome. Fertil. Steril. 90 , 1692–1700 (2008).

Balaban, B. & Urman, B. Effect of oocyte morphology on embryo development and implantation. Reprod. BioMed. Online 12 , 608–615 (2006).

Kanakasabapathy, M., Bormann, C., Thirumalaraju, P., Banerjee, R. & Shafiee, H. P. Improving the performance of deep convolutional neural networks (CNN) in embryology using synthetic machine-generated images. In Human Reproduction 35th edn, Vol. 209 (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Kanakasabapathy, M. K. et al. Adaptive adversarial neural networks for the analysis of lossy and domain-shifted datasets of medical images. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5 , 571–585 (2021).

Nayot, D., Meriano, J., Casper, R. & Alex, K. An oocyte assessment tool using machine learning; predicting blastocyst development based on a single image of an oocyte. Hum. Reprod. 35 , 129–130 (2020).

Mercuri, N., Fjeldstad, J., Krivoi, A., Meriano, J. & Nayot, D. A non-invasive, 2-dimensional (2D) image analysis artificial intelligence (AI) tool scores mature oocytes and correlates with the quality of subsequent blastocyst development. Fertil. Steril. 118 , e78–e79 (2022).

Link, C. et al. P-246 A novel non-invasive tool for oocyte selection using gene expression and artificial intelligence. Hum. Reprod. 37 , deac107–236 (2022).

Janati, S., Behmanesh, M. A., Najafzadehvarzi, H., Akhundzade, Z. & Poormoosavi, S. M. Follicular fluid zinc level and oocyte maturity and embryo quality in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 15 , 197–201 (2021).

Cheng, E.-H. et al. Evaluation of telomere length in cumulus cells as a potential biomarker of oocyte and embryo quality. Hum. Reprod. 28 , 929–936 (2013).

Kirillova, A., Smitz, J. E. J., Sukhikh, G. T. & Mazunin, I. The role of mitochondria in oocyte maturation. Cells 10 , 2484 (2021).

Lemseffer, Y., Terret, M.-E., Campillo, C. & Labrune, E. Methods for assessing oocyte quality: a review of literature. Biomedicines 10 , 2184 (2022).

Dimitriadis, I. et al. Deep convolutional neural networks (CNN) for assessment and selection of normally fertilized human embryos. Fertil. Steril. 112 , e272 (2019).

Fukunaga, N. et al. Development of an automated two pronuclei detection system on time-lapse embryo images using deep learning techniques. Reprod. Med. Biol. 19 , 286–294 (2020).

Coticchio, G. et al. Cytoplasmic movements of the early human embryo: imaging and artificial intelligence to predict blastocyst development. Reprod. Biomed. Online 42 , 521–528 (2021).

Zhao, M. et al. Application of convolutional neural network on early human embryo segmentation during in vitro fertilization. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 25 , 2633–2644 (2021).

Khosravi, P. et al. Deep learning enables robust assessment and selection of human blastocysts after in vitro fertilization. NPJ Digi. Med. 2 , 1–9 (2019).

Thirumalaraju, P. et al. Evaluation of deep convolutional neural networks in classifying human embryo images based on their morphological quality. Heliyon 7 , e06298 (2021).

Berntsen, J., Rimestad, J., Lassen, J. T., Tran, D. & Kragh, M. F. Robust and generalizable embryo selection based on artificial intelligence and time-lapse image sequences. PLoS One 17 , e0262661 (2022).

Theilgaard Lassen, J., Fly Kragh, M., Rimestad, J., Nygård Johansen, M. & Berntsen, J. Development and validation of deep learning based embryo selection across multiple days of transfer. Sci. Rep. 13 , 4235 (2023).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Diakiw, S. M. et al. An artificial intelligence model correlated with morphological and genetic features of blastocyst quality improves ranking of viable embryos. Reprod. Biomed. Online 45 , 1105–1117 (2022).

Ahlström, A. et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial investigating a time-lapse algorithm for selecting day 5 blastocysts for transfer. Hum. Reprod. 37 , 708–717 (2022).

Goodman, L. R., Goldberg, J., Falcone, T., Austin, C. & Desai, N. Does the addition of time-lapse morphokinetics in the selection of embryos for transfer improve pregnancy rates? a randomized controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 105 , 275–285 (2016).

Kieslinger, D. C. et al. Clinical outcomes of uninterrupted embryo culture with or without time-lapse-based embryo selection versus interrupted standard culture (SelecTIMO): a three-armed, multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 401 , 1438–1446 (2023).

Pribenszky, C., Nilselid, A.-M. & Montag, M. Time-lapse culture with morphokinetic embryo selection improves pregnancy and live birth chances and reduces early pregnancy loss: a meta-analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 35 , 511–520 (2017).

Hickman, C. et al. Turning the black box into a glass box: use of transparent artificial intelligence to understand biological markers useful for embryo selection. Fertil. Steril. 118 , e5–e6 (2022).

Hickman, C. et al. Comprehensive comparison of number of embryology hours per cycle and risk before and after introduction of CHLOE EQ™ (Fairtility) into a 100% time-lapse IVF clinic. Fertil. Steril. 118 , e119–e120 (2022).

Tiegs, A. W. et al. A multicenter, prospective, blinded, nonselection study evaluating the predictive value of an aneuploid diagnosis using a targeted next-generation sequencing-based preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy assay and impact of biopsy. Fertil. Steril. 115 , 627–637 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. IVF embryo choices and pregnancy outcomes. Prenat. Diagn. 41 , 1709–1717 (2021).

Hipp, H. S. et al. Trends and outcomes for preimplantation genetic testing in the United States, 2014-2018. JAMA 327 , 1288–1290 (2022).

Meseguer Escriva, M. et al. O-073 Artificial intelligence (AI) based triage for preimplantation genetic testing (PGT); an AI model that detects novel features in the embryo associated with ploidy. Hum. Reprod. 37 , deac104–087 (2022).

Barnes, J. et al. A non-invasive artificial intelligence approach for the prediction of human blastocyst ploidy: a retrospective model development and validation study. Lancet Digi. Health 5 , e28–e40 (2023).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Chavez-Badiola, A., Flores-Saiffe-Farías, A., Mendizabal-Ruiz, G., Drakeley, A. J. & Cohen, J. Embryo ranking intelligent classification algorithm (erica): artificial intelligence clinical assistant predicting embryo ploidy and implantation. Reprod. BioMed. Online 41 , 585–593 (2020).

Jiang, V. S. et al. The use of voting ensembles and patient characteristics to improve the accuracy of deep neural networks as a non-invasive method to classify embryo ploidy status. Fertil. Steril. 116 , e155–e156 (2021).

Liang, R. et al. Prediction model for day 3 embryo implantation potential based on metabolites in spent embryo culture medium. BMC Pregn. Childbirth 23 , 425 (2023).

Eldarov, C. et al. LC-MS analysis revealed the significantly different metabolic profiles in spent culture media of human embryos with distinct morphology, karyotype and implantation outcomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 , 2706 (2022).

Vergouw, C. G. et al. No evidence that embryo selection by near-infrared spectroscopy in addition to morphology is able to improve live birth rates: results from an individual patient data meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. 29 , 455–461 (2014).

Kirkegaard, K. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomic profiling of day 3 and 5 embryo culture medium does not predict pregnancy outcome in good prognosis patients: a prospective cohort study on single transferred embryos. Hum. Reprod. 29 , 2413–2420 (2014).

Lledo, B., Morales, R., Antonio Ortiz, J., Bernabeu, A. & Bernabeu, R. Noninvasive preimplantation genetic testing using the embryo spent culture medium: an update. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 35 , 294–299 (2023).

Siristatidis, C. S., Sertedaki, E., Vaidakis, D., Varounis, C. & Trivella, M. Metabolomics for improving pregnancy outcomes in women undergoing assisted reproductive technologies. Cochr. Datab. Syst. Rev. 3 , CD011872 (2018).

Cheredath, A. et al. Combining machine learning with metabolomic and embryologic data improves embryo implantation prediction. Reprod. Sci. 30 , 984–994 (2023).

Siristatidis, C. et al. Why has metabolomics so far not managed to efficiently contribute to the improvement of assisted reproduction outcomes? the answer through a review of the best available current evidence. Diagnost. Basel 11 , 1602 (2021).

Doyle, N. et al. Live birth after transfer of a single euploid vitrified-warmed blastocyst according to standard timing vs. timing as recommended by endometrial receptivity analysis. Fertil. Steril. 118 , 314–321 (2022).

Richter, K. S. & Richter, M. L. Personalized embryo transfer reduces success rates because endometrial receptivity analysis fails to accurately identify the window of implantation. Hum. Reprod. 38 , 1239–1244 (2023).

(The writing group) for the participants to the 2022 Lugano RIF Workshop. Recurrent implantation failure: reality or a statistical mirage? Consensus statement from the July 1, 2022 Lugano workshop on recurrent implantation failure. Fertil. Steril. 120 , 45–59 (2023).

Gromski, P. S. et al. Ethnic discordance in serum anti-müllerian hormone in european and indian healthy women and indian infertile women. Reprod. Biomed. Online 45 , 979–986 (2022).

Ko, J. K. et al. Comparison of the number of oocytes obtained after ovarian stimulation between chinese and caucasian women undergoing in vitro fertilization using a standardized stimulation regime. J. Ovarian Res. 14 , 175 (2021).

Loutradis, D. et al. FSH receptor gene polymorphisms have a role for different ovarian response to stimulation in patients entering IVF/ICSI-ET programs. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 23 , 177–184 (2006).

Roth, L. W. et al. Evidence of GnRH antagonist escape in obese women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99 , E871–E875 (2014).

Venetis, C. A. et al. What is the optimal GnRH antagonist protocol for ovarian stimulation during ART treatment? A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update (2023).

Garg, A. et al. Luteal phase support in assisted reproductive technology. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. (2023).

Amann, J. et al. To explain or not to explain?-artificial intelligence explainability in clinical decision support systems. PLoS Digi. Health 1 , e0000016 (2022).

Vasey, B. et al. Reporting guideline for the early-stage clinical evaluation of decision support systems driven by artificial intelligence: DECIDE-AI. Nat. Med. 28 , 924–933 (2022).

Collins, G. S. et al. Protocol for development of a reporting guideline (TRIPOD-AI) and risk of bias tool (PROBAST-AI) for diagnostic and prognostic prediction model studies based on artificial intelligence. BMJ Open 11 , e048008 (2021).

Curchoe, C. L. Proceedings of the first world conference on AI in fertility. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 40 , 215–222 (2023).

Joshi, K. et al. A proof-of-concept prospective study of applying artificial intelligence for sperm selection in the IVF laboratory. Reprod. Reprod. BioMed. Online 188 , 103329 (2023).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The Department of Metabolism, Digestion, and Reproduction is funded by grants from the MRC and NIHR. S.H. is supported by the UKRI CDT in AI for Healthcare http://ai4health.io (EP/S023283/1). A.A. is supported by an NIHR Clinician Scientist Award (CS-2018-18-ST2-002). M.V. and K.T.A. are supported by the EPSRC (EP/T017856/1). W.S.D. is supported by an NIHR Senior Investigator Award (NIHR202371).

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Simon Hanassab, Ali Abbara.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Thomas Heinis, Waljit S. Dhillo.

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Metabolism, Digestion, and Reproduction, Imperial College London, London, UK

Simon Hanassab, Ali Abbara, Arthur C. Yeung, Geoffrey H. Trew & Waljit S. Dhillo

Department of Computing, Imperial College London, London, UK

Simon Hanassab & Thomas Heinis

UKRI Centre for Doctoral Training in AI for Healthcare, Imperial College London, London, UK

Simon Hanassab

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK

Ali Abbara, Arthur C. Yeung & Waljit S. Dhillo

Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

Margaritis Voliotis & Krasimira Tsaneva-Atanasova

Living Systems Institute, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

EPSRC Hub for Quantitative Modelling in Healthcare, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

School of Computer Science, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, UK

Tom W. Kelsey

The Fertility Partnership, Oxford, UK

Geoffrey H. Trew & Scott M. Nelson

School of Medicine, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK

Scott M. Nelson

Biomedical Research Centre, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

S.H., A.A., T.H., and W.S.D. conceptualized the review. S.H., A.A., A.C.Y., M.V., and S.M.N. wrote the manuscript. M.V., K.T.A., T.W.K., and T.H. provided methodological expertise. A.A., A.C.Y., G.H.T., S.M.N., and W.S.D. provided clinical expertise. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Waljit S. Dhillo .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

A.A. has received grants from the BRC; and has provided consulting services for Myovant Sciences Ltd. G.H.T. has stock in TFP; has received honoraria and travel support from Ferring Pharmaceuticals; and has provided consultancy services to ARC Medical Inc. S.M.N. received grants from NIHR, CSO, and BRC; provided consultancy services for Access Fertility, Modern Fertility, TFP, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals; received honoraria from Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Merck; received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Merck; participated in a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for NIHR; owns stock or stock options in TFP. W.S.D. received grants from NIHR, MRC, and Imperial Health Charity, and is a Consultant for Myovant Sciences Ltd. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hanassab, S., Abbara, A., Yeung, A.C. et al. The prospect of artificial intelligence to personalize assisted reproductive technology. npj Digit. Med. 7 , 55 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01006-x

Download citation

Received : 25 January 2023

Accepted : 10 January 2024

Published : 01 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01006-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Predictive strategies for oocyte maturation in ivf cycles: from single indicators to integrated models.

Middle East Fertility Society Journal (2024)

A review of artificial intelligence applications in in vitro fertilization

- Xiaowen Liang

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Main topics in assisted reproductive market: A scoping review

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft

Affiliations Applied Molecular Biology Lab (LAPLIC), Biochemistry Department, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, Januário Cicco´s University Hospital (MEJC), Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil

Roles Data curation

Affiliation Applied Molecular Biology Lab (LAPLIC), Biochemistry Department, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Janaina Ferreira Aderaldo,

- Beatriz Helena Dantas Rodrigues de Albuquerque,

- Maryana Thalyta Ferreira Câmara de Oliveira,

- Mychelle de Medeiros Garcia Torres,

- Daniel Carlos Ferreira Lanza

- Published: August 1, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0284099

- Reader Comments

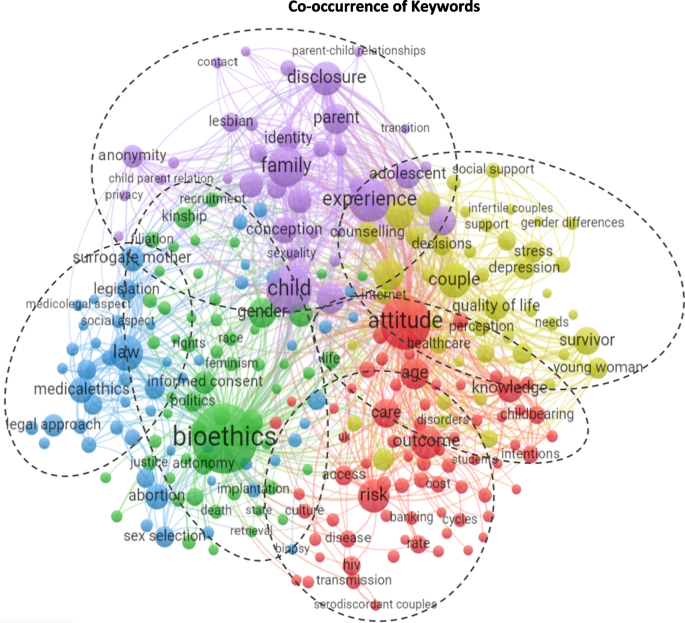

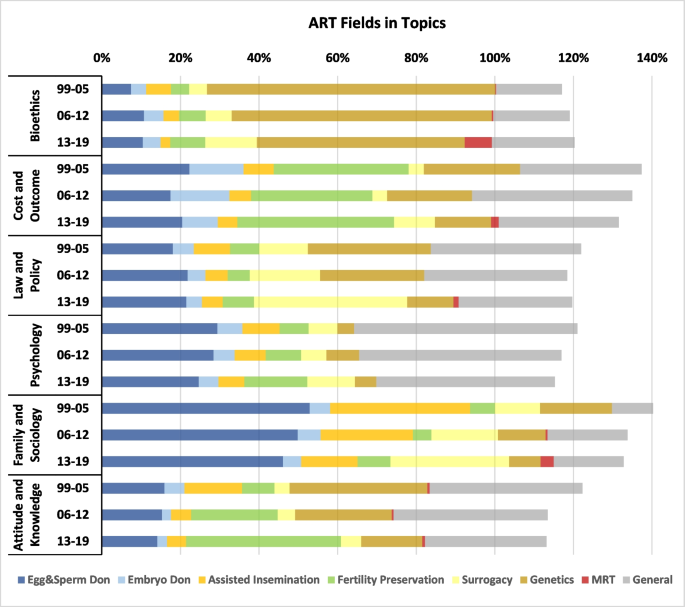

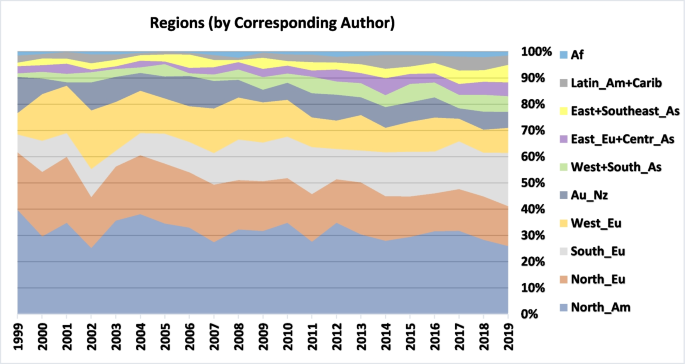

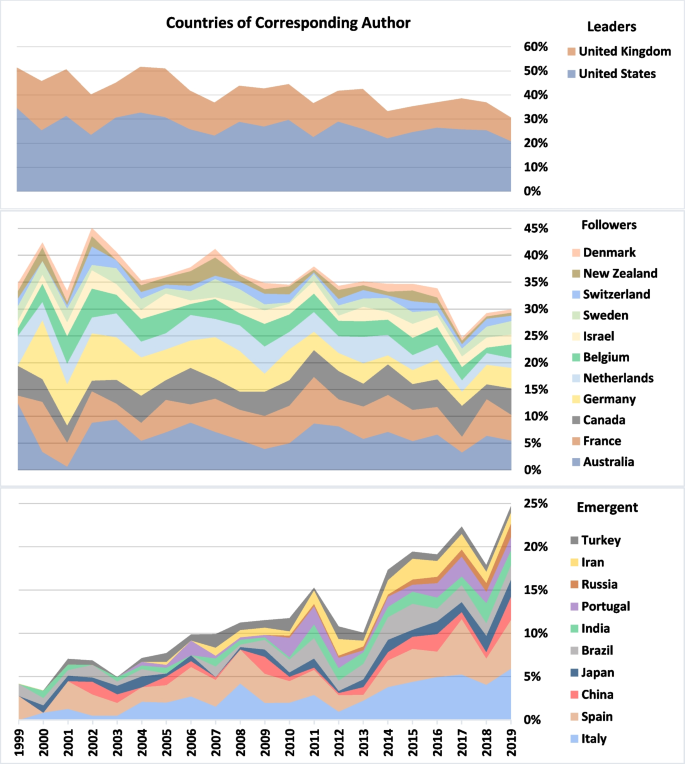

Infertility affects around 12% of couples, and this proportion has been gradually increasing. In this context, the global assisted reproductive technologies (ART) market shows significant expansion, hovering around USD 26 billion in 2019 and is expected to reach USD 45 billion by 2025.