- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

Using Observation to Guide Your Teaching

You are here

As staff assessors for NAEYC’s Early Learning Programs team, we visit different programs across the country. Our goal is to connect with program staff, observe, and gather information about a setting to evaluate it for accreditation. The NAEYC “Early Learning Program Accreditation Standards and Assessment Items” guides our work: it outlines expectations for excellence, aiming to ensure that programs offer children and families continuously high-quality early childhood education and care.

There are 10 standards covering a range of topic areas. One of the most challenging for programs is Standard 4: Assessment of Child Progress. As we gather information for this standard, we look for evidence that early childhood educators are observing children—watching and listening with intention along with recording that information—then using their observations to do two things: adjust teaching strategies and design learning experiences.

In this article, we share details and examples about how to use observations to guide instruction. These are based on our work as early childhood educators and reflect our observations of and feedback to early learning programs as they go through the accreditation process.

Teachers as Observers

Effective teachers intentionally watch and listen to children—whether during a daily routine or a planned activity, on a particular day, and over time. Sometimes, we can tell a teacher is observing by what they say. During our visits, we often hear a teacher share things like

- “Jamal is starting to recognize the letters in his name. Today he pointed to an A in a book and said, ‘That’s MY letter.’”

- “Marisu has incredible balance. Did you see how long she stood on one foot today?!”

- “Jacintha made up another song while she was in the dramatic play center today. She comes up with the most wonderful melodies.”

Other times, we can tell a teacher is observing by their documentation. Teachers use anecdotal records, audio and video recordings, checklists and rating scales, and other means to document children’s learning and growth. Documentation can be reviewed, reflected on, and used to make decisions, including the next steps in planning for a group and for individual children.

Using Observations to Adjust Teaching Strategies

Ms. Jackson and Ms. Perez coteach in an early learning program. During shared outdoor time, the two observe a group of children trying to make a tower out of loose parts cut from a tree trunk. The children are having a difficult time because they’re using a few small blocks of wood as a base and stacking larger pieces on top. The tower keeps toppling.

Ms. Jackson approaches the children. “Put the big pieces on the bottom,” she says. It’s a strategy she has used in the past: in the block center earlier that week, she told children that big blocks should go at the bottom of a structure. Then, as now, the children stare at her.

Ms. Perez takes another approach. Responding to the children as active, engaged learners, she waits and observes rather than imposing a solution. Then she says, “I remember when you were building a tower inside the other day. What happened to that tower?” She listens and watches some more. When the outside tower falls again, she says, “Hmm, I wonder what else you could try?” to encourage the children to keep working. After several failed attempts, the children collect smaller pieces of wood and line them up to make a sturdier base. It works! The tower is tall and stable.

This is an example of using the results of observation to adjust teaching strategies. Based on her observations, Ms. Perez decided to ask questions and give a clue or hint. By intentionally observing and acting on what they see, teachers can select and adapt a range of developmentally appropriate strategies to promote children’s play and work.

What to Observe

If observation is new to you or if you’re looking to finetune your current practice, consider asking the following questions as you watch the children in your setting.

- What activities and materials does each child respond to (positively or negatively)?

- What are some questions and statements each child has said that stand out to you?

- What does each child talk about?

- How does each child play?

- Who does each child enjoy playing with?

- When is each child most successful?

- When does each child smile and laugh?

Using Observations to Design Learning Experiences

While teachers have many opportunities to make spontaneous observations (as in the vignette), they can also plan when to observe and tie what they see to specific learning goals or objectives. For example, Ms. Patel was interested in learning more about what each child in her setting already knew about the alphabet. As children engaged in the literacy center over the next few weeks, she intentionally observed and asked questions as they played. She noticed that Jack named all the letters in the alphabet and used scribbles to represent letters on paper. Ms. Patel documented these observations by taking pictures and writing anecdotal records. After reviewing and reflecting on these pieces, she created more print-rich materials by adding laminated cards with words related to the weekly theme and by putting labels on toy shelves. She also made a class book with photos of each child beside their names. That helped Jack start making connections and move from scribbles to letter-like forms and letters.

In addition, teachers can draw on their observations of children’s interests as they plan related learning experiences. For example, if Ms. Patel observes that Jack is interested in reptiles, she can add sand and plastic lizards to the sensory table, encouraging Jack to use his fingers or the lizards’ tails to draw letters in the sand. She can introduce playdough rolled into long “snakes” and encourage Jack to make letter shapes with them. This is one of many examples we observed in the field of teachers using observation to design activities or learning experiences.

Questions to Help Use What You Observe

As assessors, we are trained to look for evidence that educators are using what they observe to guide teaching and inform decision making about each and every child. As you think about how you use observations in your setting, consider the following questions:

- When do I typically watch and listen to children?

- Are there other times I could be observing?

- What types of activities or experiences do I tend to watch and listen to closely?

- When else might I want to start observing?

- How do I use information from my observations?

- What is one new or different way I can use this information to guide my teaching?

Bringing It Together: Using Observations to Individualize Instruction

When teachers make the most of their observations, they can adjust their teaching approaches and design activities that are responsive to each learner in their setting. Looking back at the opening examples, here is how the teacher in each situation did just that.

Observation: “Jamal is starting to recognize the letters in his name. Today he pointed to an A in a book and said, ‘That’s MY letter.’”

Adjusted teaching strategies: Jamal’s teacher, Mr. Blanca, starts pointing out letters around the room that are in Jamal’s name. He places books in the classroom library about celebrating one’s name (such as Your Name is a Song, by Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow and illustrated by Luisa Uribe, and Chrysanthemum, by Kevin Henkes). He intentionally spends time in that area, acknowledging, giving feedback, and using other strategies as Jamal engages with these books.

Designed learning experiences: Next week, Mr. Blanca plans an activity where children will use tools like stencils, foam brushes, or their fingers to paint the letters in their names. He makes sure to draw Jamal’s attention to the art center and the opportunity to paint his name and other things about himself.

Observation: “Marisu has incredible balance. Did you see how long she stood on one foot today?!”

Adjusted teaching strategies: When the group sings during music time, Marisu’s teacher, Ms. Deepti, prompts children to add movements like hopping and standing on one foot.

Designed learning experiences: With support from Ms. Deepti, the children make an obstacle course with a balance beam. They keep the course up for a few weeks, and Ms. Deepti encourages Marisu to try this activity during that time.

Observation: “Jacintha made up another song while she was in the dramatic play center today. She comes up with the most wonderful melodies.”

Adjusted teaching strategies: Jacintha’s teacher, Ms. Brahma, sings clean-up time directions to the melody Jacintha was singing.

Designed learning experiences: Ms. Brahma plans to introduce an instructional unit on melodies in children’s songs. She will gather ideas from the children, from collections at the local library, and from families. She anticipates making melody maps (posters with different shapes that visually show a melody) and talking about high and low sounds. She also plans to incorporate different genres or styles of music from various cultures into the class’s daily routines.

Photographs: © Getty Images Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See permissions and reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions .

Dawn Petitpas has been an assessor at NAEYC for 20 years and has observed in thousands of early childhood classrooms. She has a bachelor’s degree in early childhood and child care leadership from Leslie University and a master’s degree in school administration from Wheelock.

Teresa K. Buchanan, PhD, started assessing programs for NAEYC in 2021. She was an early childhood teacher educator for 20 years and earned her doctorate in child and family studies with a focus on early childhood education from Purdue University.

Vol. 16, No. 1

Print this article

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

CHAPTER 4 – OBSERVATION, DOCUMENTATION, & ASSESSMENT

Naeyc standards.

The following NAEYC Standard for Early Childhood Professional Preparation is addressed in this chapter:

Standard 3: Observing, documenting, and assessing to support young children and families.

Standard 6: Becoming a professional

PENNSYLVANIA EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATOR COMPETENCIES

The following competencies are addressed in this chapter:

Child Growth and Development

Families, Schools and Community Collaboration and Partnerships

Health, Safety, and Nutrition

Curriculum and Learning Experiences

Professionalism and Leadership

Communication

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE EDUCATION OF YOUNG CHILDREN (NAEYC) CODE OF ETHICAL CONDUCT (MAY 2011)

The following elements of the code are touched upon in this chapter:

Section I: Ethical Responsibilities to Children

Ideals: – I-1.1-, I-1.2, I-1.3, I-1.6, I-1.7, I-1.10

Principles: P-1.1, P-1.2, P-1.4, P-1.5, P-6, P-1.7,

Section II: Ethical Responsibilities to Families

Ideals: I-2.1, I-2.2, I-2.3, I-2.4, I-2.5, I-2.6, I-2.7, I-2.8

Principles: P-2.4, P-2.6, P-2.7, P-2.8, P-2.12, P-2.13

Ethical Responsibilities to Colleagues (Co-Workers and Employers) Ideals: I-3A.3, I-3B.1

Section IV: Ethical Responsibilities to Community and Society Ideals: I-4.1, I-4.2, I-4.5

As discussed in chapter 2, the field of early care and education relies on developmental and learning theories to guide our practices. Not only do theories help us to better understand a child’s social, emotional, cognitive, and physical needs, but theories help us to see each child as a unique learner and can also help us to set appropriate expectations. With the information we uncover by watching and listening to children, we can provide developmentally appropriate learning opportunities so they can thrive. In this chapter, we will examine how observation techniques are used to connect theory principles to practical applications. In other words, we will explore how teachers can incorporate observation, documentation, and assessment into their daily routines in order to effectively work with children and their families.

In the field of early care and education, the pursuit of high-quality care is a top priority. Throughout the day, preschool teachers have numerous tasks and responsibilities. In addition to providing a safe and nurturing environment, teachers must plan an effective curriculum, assess development, decorate the classroom, stock the shelves with age-appropriate materials, and they must develop respectful relationships with children and their families. So you might be wondering, what does this all have to do with observation, documentation, and assessment? To effectively support a child’s development and to help them thrive, preschool teachers are expected to be accountable and intentional with every interaction and experience. Let’s take a closer look and examine how teachers utilize observation, documentation, and assessment to maintain a high-quality learning environment.

THE PURPOSE OF OBSERVATION

Regular and systematic observations allow us to reflect on all aspects of our job as early childhood educators. To ensure high-quality practices we should observe the program environment, the interactions between the children and teachers, and each child’s development. With the information we gather from ongoing observations we can:

Improve teaching practices

Plan curriculum

Assess children’s development

Partner with families

Let’s review each concept more closely to better understand why we observe .

To Improve Teaching Practices

As we watch and listen to children throughout the day, we begin to see them for who they are. With each interaction and experience, we can see how children process information and how they socialize with their peers. We can learn so much about a child if we take the time to watch, listen, and record on a daily basis. Teachers are sometimes influenced by their own ideas of how children should behave. Truth be told, everything passes through a filter that is based on the observer’s beliefs, cultural practices, and personal experiences. As observers, we must be aware that our own biases can impact our objectivity. To gain perspective and to be most effective, we must train ourselves to slow down and step back, we must try to focus on what the child is actually doing, rather than judging how they are doing it or assuming why they are doing it. To practice becoming more objective, imagine you are a camera taking snapshots of key moments. As you observe the children in your care – practice recording just the facts. xxxvii

To Plan Effective Curriculum

When I was a teacher some years ago, I planned activities and set up the environment based on my interests and ideas of what I thought children should be learning. Today I realize that optimal learning occurs when the curriculum reflects the children’s interests. To uncover their interests, teachers need to observe each child as an individual, in addition to observing both small and large group interactions. Let’s look at the curriculum cycle to examine best practices in how to use observation to plan an effective curriculum.

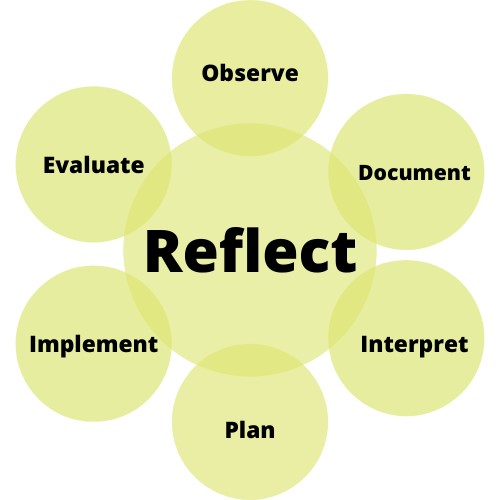

Figure 3.1 Reflection xxxviii

Reflective Practice is at the center of the curriculum planning cycle. Reflective practice helps us to consider our caregiving practices and to develop greater self-awareness so we can be more sensitive and responsive to the children we care for. As we look, listen, and record the conversations and interactions of each child, we are collecting valuable insight. With each observation, we are learning specific details about the children’s interests and abilities, their play patterns, social behaviors, problem-solving skills, and much, much more. With the information we gather, we can reflect on our caregiving practices and look at what we are doing well in addition to where we can improve. To ensure best practices, we can think about how we can become more responsive and how we can meet each child where they are in order to best support their individual needs. Reflective practice can be done alone or with co-workers – if you are team teaching. To create an inclusive learning environment that engages each child in meaningful ways, here are some prompts to help you begin reflecting on your practices:

look at the space, materials, and daily schedule;

Consider the cultural diversity of families;

Think about whether caregiving routines are meaningful;

Think about how you are fostering relationships with families

Consider if you are using a “one size fits all” approach

Think about if your expectations for children match up with the age and stage of their development

Reflect on how you are guiding children’s behavior

Let’s take a closer look at how the cycle works to help us plan and implement a developmentally appropriate curriculum.

To gather useful information about each child, we must first remember to use an objective lens . In other words, rather than assuming you know what a child is thinking or doing, it is important to learn the art of observing. To gather authentic evidence, we must learn how to look and listen with an open mind. We must learn to “see” each child for who they are rather than for who we want them to be or who we think they should be. Be assured, that learning to be an objective observer is a skill that requires patience and practice. As you begin to incorporate observation into your daily routine, here are a few things to think about:

Who should I observe? Quite simply – every child needs to be observed. Some children may stand out more than others, and you may connect to certain children more than others. In either case, be aware and be mindful to set time aside to observe each child in your care.

When should I observe? It is highly suggested that you observe at various times throughout the day – during both morning and afternoon routines. Some key times may include during drop-off and pick-up times, during planned or teacher-directed activities, during open exploration, or during child-initiated activities. You may have spontaneous observations – which are special moments or interactions that unexpectedly pop up, and you may have planned observations – which are scheduled observations that are more focused on collecting evidence about a particular skill set, interaction, or behavior.

Where should I observe? You should observe EVERYWHERE! Because children can behave differently when they are indoors as compared to when they are outdoors, it’s important to capture them interacting in both settings.

What should I observe? To understand the “whole child” you need to observe their social interactions, their physical development, how they manage their emotions and feelings, how they problem-solve when tasked with new developmental skills, how they communicate with their peers and adults, and how they use materials and follow directions. In other words – EVERYTHING a child does and says! In addition to observing each child as an individual, it’s important to look at small group interactions, along with large group interactions.

How should I observe? To capture all the various moments, you need to know when to step in and when to step back. Sometimes we quietly watch as moments occur, and sometimes we are there to ask questions and prompt (or scaffold) children’s learning.

Sometimes we can record our observations at that moment as they occur, and sometimes we have to wait to jot down what we heard or saw at a later time.

As we observe, we must record what we see and hear exactly as it happens. There are several tools and techniques that can be used to document our observations. As you continue along the Early Childhood Education / Child Development pathway, you may take a class on “Observation and Assessment” which will provide you with detailed information on how to effectively document a child’s development. As for now, we will take a brief look at some of the tools and techniques you may want to use as part of your daily routine.

Figure 3.2 Documenting what you observe is an important part of the process. xxxix

Tools to Use In Your Daily Routine

Running record.

To gather authentic evidence of everything you see and hear a child doing during a specific timeframe, you can use a running record . The primary goal of using a running record is to “obtain a detailed, objective account of behavior without inference, interpretations, or evaluations”. According to Bentzen, you will know you have gathered good evidence when you can close your eyes and you can “see” the images in your mind as they are described in your running record. xl

Anecdotal Record

Whereas a running record can be used to gather general information more spontaneously, anecdotal records are brief, focused accounts of a specific event or activity. An anecdotal record is “an informal observation method often used by teachers as an aid to understanding the child’s personality or behavior.” xli Anecdotal records, also referred to as “anecdotal notes,” are direct observations of a child that offer a window of opportunity to see into a child’s actions, interactions, and reactions to people and events. They are an excellent tool that provides you with a collection of narratives that can be used to showcase a child’s progress over time.

Developmental Checklists

To track a child’s growth development and development in all of the developmental domains including physical, cognitive, language, social, and emotional you will want to use a developmental checklist. With a checklist, you can easily see what a child can do, as well as note the areas of development that need further support. Teachers can create their own checklists based on certain skill sets, or to look at a child’s full range of development they can download a formal developmental milestone checklist from a reputable source (e.g., the CDC Developmental Milestones)

(https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/pdf/checklists/all_checklists.pdf). Checklists can be used to track a large group of children or an individual child.

Frequency Counts

To gather information about a child’s interests, social interactions, play patterns, and temperamental traits you can use a frequency count chart. As you observe the children at play, a tally mark is made every time the noted behavior or action occurs within a set timeframe. Frequency counts are also used to track undesirable or challenging behaviors, as well as prosocial behaviors.

Work Samples

Creating a work sample requires more effort than hanging a child’s picture on the wall. A work sample provides tangible evidence of a child’s effort, progress, and achievement. Not only does a work sample highlight the final product , but it can also highlight the process. To collect authentic evidence , with every work sample you need to include the date and a brief caption that explains the child’s learning experience.

Documentation Boards

In addition to using the above tools and techniques to record observations, teachers can use documentation boards or panels to highlight the learning activities that are happening throughout the week, month, and year. Not only do families enjoy seeing their child’s work posted, but children can also be empowered by seeing all that they have accomplished. Documentation boards are another great way to validate progress over time. Documentation boards can be made with the children as a project or can be assembled by the teacher or parent volunteer. Typically, documentation boards are posted on the wall for all to see and they usually showcase the following information:

Learning goals and objectives

Children’s language development

The process and complete project

The milestones of development

Photos with detailed captions

After you have captured key evidence, you must now make sense of it all. In other words, you must try to figure out what it all means. As you begin to analyze and interpret your documentation, you will want to compare your current observations to previous observations. As you compare observations, you will want to look for play patterns and track social interactions. You will also want to look for changes in behavior and look for possible triggers (antecedents) when addressing challenging behaviors.

Lastly, you will want to note any new milestones that have developed since the last observation. To help you analyze and interpret your observation data, you will want to ask yourself some reflective questions. Here are some suggested questions:

What have I learned about this child?

What are their current interests – who do they play with and what activity centers or areas do they migrate to the most?

Has this child developed any new skills or mastered any milestones?

How did this child approach new activities or problem-solve when faced with a challenge?

How long does the child usually stay focused on a task?

Is this behavior “typical” for this child?

*What can I plan to support and encourage this child to progress along at a developmentally appropriate pace?

Another vital step in interpreting your observations is to reflect and connect your observation data to developmental theories. ECE theories provide foundational principles that we use to guide our practices and plan developmentally appropriate curricula.

Once you have interpreted your observation data (asked questions, looked for patterns, noted any changes in growth and development) and analyzed theory principles, it is time to plan the curriculum. First, let’s define curriculum . According to Epstein (2007), the curriculum is “the knowledge and skills teachers are expected to teach and children are expected to learn, and the plans for experiences through which learning will take place (p. 5). I would like to define curriculum as “the activities, experiences, and interactions a child may have throughout their day.” The curriculum supports learning and play and it influences a whole child’s growth and development. As teachers set goals and make plans, they should consider that some curricula will be planned, while some curricula will emerge. As you plan your curriculum, you are encouraged to think about the following aspects of the curriculum – the environment, materials, and interactions. For example,

How is the environment set up – is it overstimulating, cluttered, or inviting and well organized?

What is the mood and tone of the classroom – is it calm or chaotic? Do the children appear happy and engaged? Have you interacted with the children?

Are there enough materials available – are children having to wait long periods of time for items and are there conflicts because of limited materials ?

Do the materials reflect the children’s interests – are they engaging and accessible?

What are the social interactions – who is playing with whom, are there social cliques, is anyone playing alone?

Are the activities appropriate – do they support development in all areas of learning?

Are there a variety of activities to encourage both individualized play and cooperative play ? xlii

Implementation

Probably the more joyful part of our job is implementing the curriculum and seeing the children engage in new activities. It is common to hear teachers say that the highlight of their day is “seeing the lightbulb go on” as children make valuable connections to what the teacher has planned and as the children master new skill sets. An important part of implementation is understanding differentiated instruction . According to Gordon and Browne (2016) when teachers can implement activities and materials to match the interests and skill level of each child, they are utilizing developmentally appropriate practices. For light bulbs to go off, intentional teachers must remember to “tailor what is taught to what a child is ready and willing to learn.”

Once you have planned your curriculum, gathered your materials, set up your environment, and implemented your activities, you will need to observe, document, and interpret the interactions so that you can evaluate and plan for the next step. Based on whether the children mastered the goals, and expectations, and met the learning outcomes will determine your next step. For example, if the children can quickly and easily complete the task, you may have to consider adding more steps or extending the activity to challenge the children. If some children were unable to complete the task or appeared uninterested, you may consider how to better scaffold their learning either through peer interactions or by redefining the steps to complete the activity. As you evaluate your implemented activities here are some questions that you want to think about:

How did the child approach the activity and how long did the child stay engaged?

What problem-solving strategies did the child use?

Did the child follow the intended directions or find alternative approaches?

Who did the child interact with?

Based on your answers, you will decide on what is in the child’s best interest and how to proceed moving forward.

Figure 3.3 Evaluating the curriculum you implement helps you decide how to move forward. xliii

To Assess Children’s Development

Early childhood educators use assessments to showcase critical information about a child’s growth and development. As suggested by Gordon and Brown (2016) “Children are evaluated because teachers and parents want to know what the children are learning.” It is important to note that “assessment is not testing. xliv

Assessment is, however, a critical part of a high-quality early childhood program and is used to:

Provide a record of growth in all developmental areas: cognitive, physical/motor, language, social-emotional, and approaches to learning.

Identify children who may need additional support and determine if there is a need for intervention or support services.

Help educators plan individualized instruction for a child or for a group of children that are at the same stage of development.

Identify the strengths and weaknesses within a program and information on how well the program meets the goals and needs of the children.

Provide a common ground between educators and parents or families to use in collaborating on a strategy to support their child.

The key to a good assessment is observation. xlvi Whether you obtain your observation evidence through spontaneous or planned observations, it is suggested that you document your observations by utilizing various tools and techniques (e.g. running records, anecdotal notes, checklists, frequency counts, work samples, learning stories). As teachers watch children in natural settings, they can gather evidence that can then be used to track a child’s learning, growth, and development throughout the school year. To start the assessment process, here is a road map for you to follow:

Step 1: Gather Baseline Data

Step 2 : Monitor Each Child’s Progress

Step 3 : Have a Systematic Plan in Place

Let’s look at each step more closely.

Step 1. Establish a Baseline

Before you can assess a child’s development, you must get to know your child. The first step is to gather “baseline” information. Through ongoing observation, you learn about each child’s strengths, interests, and skills. While observing you may also uncover a child’s unique learning styles, needs, or possible barriers that may limit them from optimal learning opportunities. For example, you may notice that when a child arrives in the morning, they tend to sit quietly at the table, and they don’t engage with other children or join in play activities. As you track the behavior, you begin to see a pattern that when a teacher sits with the child and they read a story together, the child warms up much faster than when left alone. Baseline information provides you with a starting point that can help you build a respectful relationship with each child in your class.

Step 2. Monitor Progress

“The goal of observing children is to understand them better” (Gordon & Browne, 2016, p.119). Observations help guide our decisions, inform our practices, and help us to develop a plan of action that best fits each child’s individual needs. With every observation, we can begin to see how all the pieces fit together to make the whole child . To successfully monitor a child’s progress, we must look at the following:

The child’s social interactions

The child’s play preferences

How the child handles their feelings and emotions

The timeframe in which the child masters developmental milestones

How the child processes information and is able to move on to the next activity or level

With each observation, you gather more information and more evidence that can be used to assess the child’s development.

Step 3. A Systematic Plan

Once you have gathered an array of evidence, it is time to organize it. There are two different types of assessment systems:

Program-developed child assessment tools are developed to align with a specific program’s philosophy and curriculum.

Published child assessment tools have been researched and tested and are accepted as credible sources for assessing children’s development.

Forms of Assessment

Whichever system is in place in your program, you will need to be trained accordingly. In this section, we will highlight the use of portfolios and learning stories, as well as discuss the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS, 2008) as featured assessment systems that can be used to track a child’s development.

Portfolios help teachers organize all the work samples, anecdotal notes, checklists, and learning stories that have been collected for each child throughout the school year. A portfolio is similar to a traditional photograph album, but it is much more than an album. A portfolio is “an intentional compilation of materials and resources collected over time” (Gordon and Browne, 2016, p. 112). A portfolio is not an assessment tool in and of itself, it is a collection of written observation notes for each photo and work sample. The evidence clearly documents a child’s progression over time. Portfolios are important tools in helping to facilitate a partnership between teachers and parents. During conferences, teachers can showcase the portfolio as they share anecdotes of the child’s progress. Parents (and children) enjoy seeing all the achievements and chronological growth that has occurred during the school year.

Digital portfolios or e-Portfolios are trending now as technology has become more accessible. Not only do e-Portfolios enable teachers to document children’s activities faster, but teachers can also now post information and communicate with families on a regular basis, rather than waiting until the end of the school year for a traditional family conference.

What are the strengths of portfolios?

Information in a portfolio is organized in a chronological order

Portfolios promote a shared approach to decision-making that can include the parent and child and teacher.

Portfolios do not have the same constraints and narrow focus as standardized tests.

Portfolios help teachers to keep track of a child’s development over time

Portfolios can help teachers develop richer relationships with the children in their classroom

What are the limitations of portfolios?

Creating and maintaining a portfolio requires a large investment of time and energy

Currently, there are no valid grading criteria to evaluate portfolios since outcomes can vary from one child to another

Maintaining objectively can be challenging

Learning Stories

Learning Stories are written records that document what a teacher has observed a child doing. It becomes an actual learning story when the teacher adds his or her interpretation of the child’s dispositions toward learning – such as grit, courage, curiosity, and perseverance. The story may be as short as one paragraph or as long as one page. Much like an anecdotal record, teachers observe and document brief moments as a child engages with peers or completes a task. With the learning story, however, the teacher connects learning goals and highlights developmental milestones that the child is mastering. With learning stories, teachers tend to focus on what the child can do rather than what they can’t do. With almost all learning stories, teachers will take photographs (or video) to include with the written story.

What are the strengths of learning stories?

By listening to, observing, and recording children’s explorations, you send them a clear message that you value their ideas and thinking.

As the teacher shares the Learning Story with the child, the child has the opportunity to reflect on his or her own development, thinking, and learning.

The whole class can listen and participate in each other’s stories and ideas.

Learning stories provide parents with insight into how teachers plan for their children’s learning.

Parents uncover that teachers are thoughtful and continuous learners.

Learning Stories encourage families and children to talk about school experiences.

Learning Stories showcase how powerful and capable children really are

What are the limitations of learning stories?

The quality of the learning story depends on the teacher’s own subjectivity (ie:

viewpoints, values, and feelings towards the child)

Learning stories provide only a small snapshot of a child’s learning.

It takes time to write a learning story (teachers may only be able to write 1 or 2 stories per month) and critics argue that this may limit the amount of information a teacher will need to truly track a child’s development

Because learning stories are relatively new, there aren’t official guidelines on how often to write learning stories and what exactly they should be included

Learning stories are written up after the event or interaction has actually happened – so teachers need to have a good and accurate memory!

Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS)

The Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) is a standardized assessment tool that was developed by Robert C. Pianta, Ph. D., is Dean of the Curry School of Education, Director of the Center for Advanced Study in Teaching and Learning, and Novartis U.S. Foundation Professor of Education at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

(this system is used in Head Start Programs, Keystone STARS programs, and before and after school programs). The assessment results are intended to guide program improvement and to support teachers develop curricula to meet children’s individualized needs.

What are the strengths of the CLASS?

The CLASS is aligned with Pennsylvania’s Early Learning Standards.

The CLASS incorporates authentic observation, documentation, and reflection.

The CLASS measures each child’s individual level of growth and development in all domains of development.

What are the limitations of the CLASS?

Training teachers to be objective observers and aware of their biases can be challenging, especially with limited professional development opportunities.

The tool may be considered rigid.

Assessment, in general, is time-consuming

PARTNERSHIPS WITH FAMILIES

In addition to strengthening relationships with children, sharing observations with children’s families strengthens the home–program connection. Families must be “provided opportunities to increase their child observation skills and to share assessments with staff that will help plan the learning experiences.” xlvii

Families are with their children in all kinds of places and doing all sorts of activities. Their view of their child is even bigger than the teachers. How can families and teachers share their observations, and their assessment information, with each other? They can share through brief informal conversations, maybe at drop-off or pickup time, or when parents volunteer or visit the classroom. families and teachers also share their observations during longer and more formal times. Home visits and conferences are opportunities to chat a little longer and spend time talking about what the child is learning, what happens at home as well as what happens at school, how much progress the child is making, and perhaps to problem solve if the child is struggling and figure out the best ways to support the child’s continued learning. xlviii Partnering with families will be discussed more in Chapter 8.

Effectively working with children and families, means that teachers must effectively use observation, documentation, and assessment. We use the cycle of assessment to help improve teaching practices, plan effective curriculum, and assess children’s development. Families should be seen as partners in this process. Teachers must ensure that there is effective communication to support these relationships.

Chapter 5 (Developmental Ages and Stages) will build on observation to explore how we use the information gathered to define each unique stage of a child’s development.

ECE Principles and Practices Prek-4 Copyright © by Alison Angelaccio is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

IMAGES

VIDEO