Report | Wages, Incomes, and Wealth

“Women’s work” and the gender pay gap : How discrimination, societal norms, and other forces affect women’s occupational choices—and their pay

Report • By Jessica Schieder and Elise Gould • July 20, 2016

Download PDF

Press release

Share this page:

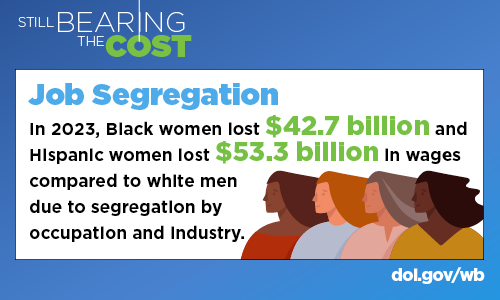

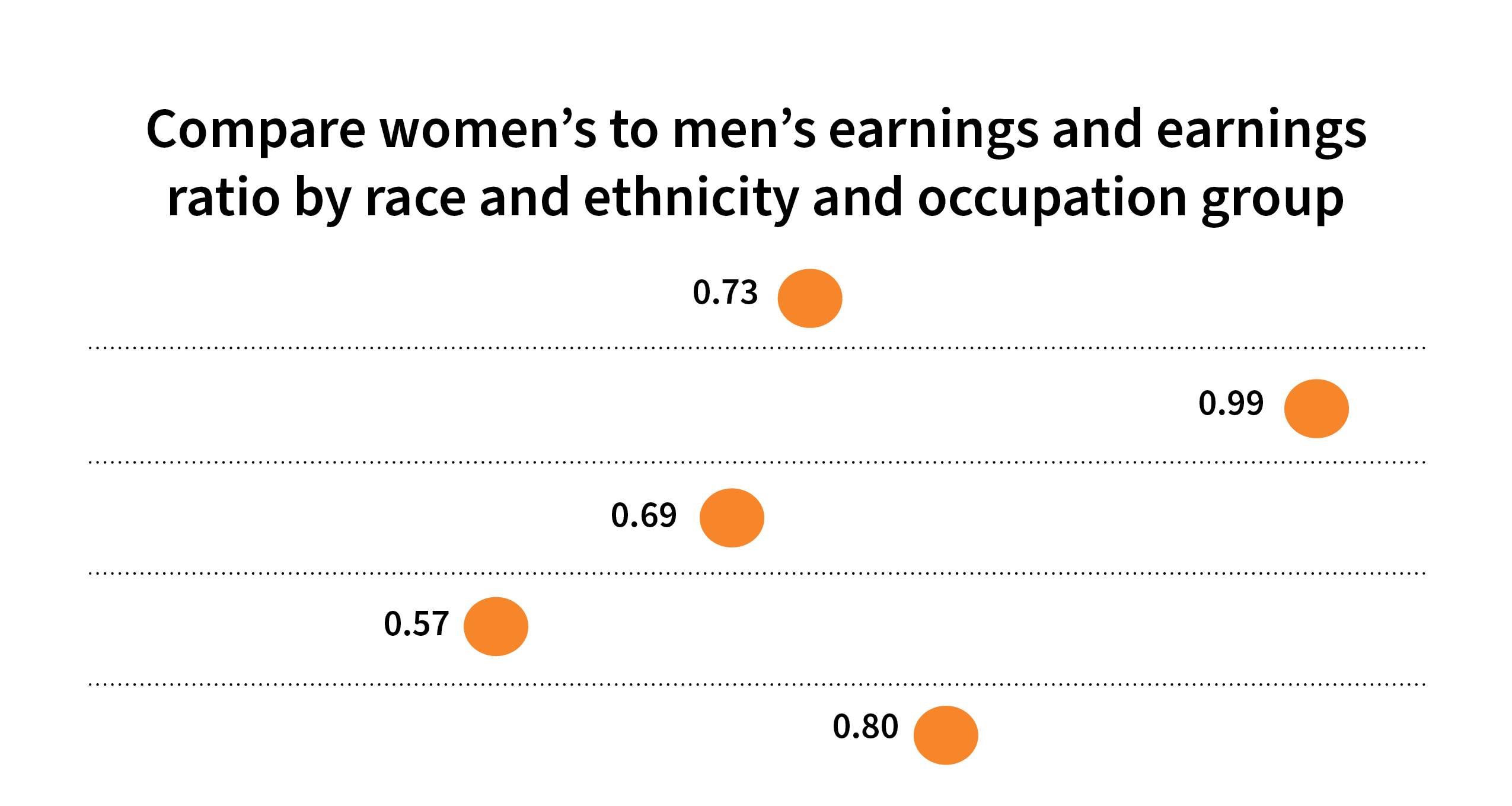

What this report finds: Women are paid 79 cents for every dollar paid to men—despite the fact that over the last several decades millions more women have joined the workforce and made huge gains in their educational attainment. Too often it is assumed that this pay gap is not evidence of discrimination, but is instead a statistical artifact of failing to adjust for factors that could drive earnings differences between men and women. However, these factors—particularly occupational differences between women and men—are themselves often affected by gender bias. For example, by the time a woman earns her first dollar, her occupational choice is the culmination of years of education, guidance by mentors, expectations set by those who raised her, hiring practices of firms, and widespread norms and expectations about work–family balance held by employers, co-workers, and society. In other words, even though women disproportionately enter lower-paid, female-dominated occupations, this decision is shaped by discrimination, societal norms, and other forces beyond women’s control.

Why it matters, and how to fix it: The gender wage gap is real—and hurts women across the board by suppressing their earnings and making it harder to balance work and family. Serious attempts to understand the gender wage gap should not include shifting the blame to women for not earning more. Rather, these attempts should examine where our economy provides unequal opportunities for women at every point of their education, training, and career choices.

Introduction and key findings

Women are paid 79 cents for every dollar paid to men (Hegewisch and DuMonthier 2016). This is despite the fact that over the last several decades millions more women have joined the workforce and made huge gains in their educational attainment.

Critics of this widely cited statistic claim it is not solid evidence of economic discrimination against women because it is unadjusted for characteristics other than gender that can affect earnings, such as years of education, work experience, and location. Many of these skeptics contend that the gender wage gap is driven not by discrimination, but instead by voluntary choices made by men and women—particularly the choice of occupation in which they work. And occupational differences certainly do matter—occupation and industry account for about half of the overall gender wage gap (Blau and Kahn 2016).

To isolate the impact of overt gender discrimination—such as a woman being paid less than her male coworker for doing the exact same job—it is typical to adjust for such characteristics. But these adjusted statistics can radically understate the potential for gender discrimination to suppress women’s earnings. This is because gender discrimination does not occur only in employers’ pay-setting practices. It can happen at every stage leading to women’s labor market outcomes.

Take one key example: occupation of employment. While controlling for occupation does indeed reduce the measured gender wage gap, the sorting of genders into different occupations can itself be driven (at least in part) by discrimination. By the time a woman earns her first dollar, her occupational choice is the culmination of years of education, guidance by mentors, expectations set by those who raised her, hiring practices of firms, and widespread norms and expectations about work–family balance held by employers, co-workers, and society. In other words, even though women disproportionately enter lower-paid, female-dominated occupations, this decision is shaped by discrimination, societal norms, and other forces beyond women’s control.

This paper explains why gender occupational sorting is itself part of the discrimination women face, examines how this sorting is shaped by societal and economic forces, and explains that gender pay gaps are present even within occupations.

Key points include:

- Gender pay gaps within occupations persist, even after accounting for years of experience, hours worked, and education.

- Decisions women make about their occupation and career do not happen in a vacuum—they are also shaped by society.

- The long hours required by the highest-paid occupations can make it difficult for women to succeed, since women tend to shoulder the majority of family caretaking duties.

- Many professions dominated by women are low paid, and professions that have become female-dominated have become lower paid.

This report examines wages on an hourly basis. Technically, this is an adjusted gender wage gap measure. As opposed to weekly or annual earnings, hourly earnings ignore the fact that men work more hours on average throughout a week or year. Thus, the hourly gender wage gap is a bit smaller than the 79 percent figure cited earlier. This minor adjustment allows for a comparison of women’s and men’s wages without assuming that women, who still shoulder a disproportionate amount of responsibilities at home, would be able or willing to work as many hours as their male counterparts. Examining the hourly gender wage gap allows for a more thorough conversation about how many factors create the wage gap women experience when they cash their paychecks.

Within-occupation gender wage gaps are large—and persist after controlling for education and other factors

Those keen on downplaying the gender wage gap often claim women voluntarily choose lower pay by disproportionately going into stereotypically female professions or by seeking out lower-paid positions. But even when men and women work in the same occupation—whether as hairdressers, cosmetologists, nurses, teachers, computer engineers, mechanical engineers, or construction workers—men make more, on average, than women (CPS microdata 2011–2015).

As a thought experiment, imagine if women’s occupational distribution mirrored men’s. For example, if 2 percent of men are carpenters, suppose 2 percent of women become carpenters. What would this do to the wage gap? After controlling for differences in education and preferences for full-time work, Goldin (2014) finds that 32 percent of the gender pay gap would be closed.

However, leaving women in their current occupations and just closing the gaps between women and their male counterparts within occupations (e.g., if male and female civil engineers made the same per hour) would close 68 percent of the gap. This means examining why waiters and waitresses, for example, with the same education and work experience do not make the same amount per hour. To quote Goldin:

Another way to measure the effect of occupation is to ask what would happen to the aggregate gender gap if one equalized earnings by gender within each occupation or, instead, evened their proportions for each occupation. The answer is that equalizing earnings within each occupation matters far more than equalizing the proportions by each occupation. (Goldin 2014)

This phenomenon is not limited to low-skilled occupations, and women cannot educate themselves out of the gender wage gap (at least in terms of broad formal credentials). Indeed, women’s educational attainment outpaces men’s; 37.0 percent of women have a college or advanced degree, as compared with 32.5 percent of men (CPS ORG 2015). Furthermore, women earn less per hour at every education level, on average. As shown in Figure A , men with a college degree make more per hour than women with an advanced degree. Likewise, men with a high school degree make more per hour than women who attended college but did not graduate. Even straight out of college, women make $4 less per hour than men—a gap that has grown since 2000 (Kroeger, Cooke, and Gould 2016).

Women earn less than men at every education level : Average hourly wages, by gender and education, 2015

| Education level | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Less than high school | $13.93 | $10.89 |

| High school | $18.61 | $14.57 |

| Some college | $20.95 | $16.59 |

| College | $35.23 | $26.51 |

| Advanced degree | $45.84 | $33.65 |

The data below can be saved or copied directly into Excel.

The data underlying the figure.

Source : EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

Copy the code below to embed this chart on your website.

Steering women to certain educational and professional career paths—as well as outright discrimination—can lead to different occupational outcomes

The gender pay gap is driven at least in part by the cumulative impact of many instances over the course of women’s lives when they are treated differently than their male peers. Girls can be steered toward gender-normative careers from a very early age. At a time when parental influence is key, parents are often more likely to expect their sons, rather than their daughters, to work in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) fields, even when their daughters perform at the same level in mathematics (OECD 2015).

Expectations can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. A 2005 study found third-grade girls rated their math competency scores much lower than boys’, even when these girls’ performance did not lag behind that of their male counterparts (Herbert and Stipek 2005). Similarly, in states where people were more likely to say that “women [are] better suited for home” and “math is for boys,” girls were more likely to have lower math scores and higher reading scores (Pope and Sydnor 2010). While this only establishes a correlation, there is no reason to believe gender aptitude in reading and math would otherwise be related to geography. Parental expectations can impact performance by influencing their children’s self-confidence because self-confidence is associated with higher test scores (OECD 2015).

By the time young women graduate from high school and enter college, they already evaluate their career opportunities differently than young men do. Figure B shows college freshmen’s intended majors by gender. While women have increasingly gone into medical school and continue to dominate the nursing field, women are significantly less likely to arrive at college interested in engineering, computer science, or physics, as compared with their male counterparts.

Women arrive at college less interested in STEM fields as compared with their male counterparts : Intent of first-year college students to major in select STEM fields, by gender, 2014

| Intended major | Percentage of men | Percentage of women |

|---|---|---|

| Biological and life sciences | 11% | 16% |

| Engineering | 19% | 6% |

| Chemistry | 1% | 1% |

| Computer science | 6% | 1% |

| Mathematics/ statistics | 1% | 1% |

| Physics | 1% | 0.3% |

Source: EPI adaptation of Corbett and Hill (2015) analysis of Eagan et al. (2014)

These decisions to allow doors to lucrative job opportunities to close do not take place in a vacuum. Many factors might make it difficult for a young woman to see herself working in computer science or a similarly remunerative field. A particularly depressing example is the well-publicized evidence of sexism in the tech industry (Hewlett et al. 2008). Unfortunately, tech isn’t the only STEM field with this problem.

Young women may be discouraged from certain career paths because of industry culture. Even for women who go against the grain and pursue STEM careers, if employers in the industry foster an environment hostile to women’s participation, the share of women in these occupations will be limited. One 2008 study found that “52 percent of highly qualified females working for SET [science, technology, and engineering] companies quit their jobs, driven out by hostile work environments and extreme job pressures” (Hewlett et al. 2008). Extreme job pressures are defined as working more than 100 hours per week, needing to be available 24/7, working with or managing colleagues in multiple time zones, and feeling pressure to put in extensive face time (Hewlett et al. 2008). As compared with men, more than twice as many women engage in housework on a daily basis, and women spend twice as much time caring for other household members (BLS 2015). Because of these cultural norms, women are less likely to be able to handle these extreme work pressures. In addition, 63 percent of women in SET workplaces experience sexual harassment (Hewlett et al. 2008). To make matters worse, 51 percent abandon their SET training when they quit their job. All of these factors play a role in steering women away from highly paid occupations, particularly in STEM fields.

The long hours required for some of the highest-paid occupations are incompatible with historically gendered family responsibilities

Those seeking to downplay the gender wage gap often suggest that women who work hard enough and reach the apex of their field will see the full fruits of their labor. In reality, however, the gender wage gap is wider for those with higher earnings. Women in the top 95th percentile of the wage distribution experience a much larger gender pay gap than lower-paid women.

Again, this large gender pay gap between the highest earners is partially driven by gender bias. Harvard economist Claudia Goldin (2014) posits that high-wage firms have adopted pay-setting practices that disproportionately reward individuals who work very long and very particular hours. This means that even if men and women are equally productive per hour, individuals—disproportionately men—who are more likely to work excessive hours and be available at particular off-hours are paid more highly (Hersch and Stratton 2002; Goldin 2014; Landers, Rebitzer, and Taylor 1996).

It is clear why this disadvantages women. Social norms and expectations exert pressure on women to bear a disproportionate share of domestic work—particularly caring for children and elderly parents. This can make it particularly difficult for them (relative to their male peers) to be available at the drop of a hat on a Sunday evening after working a 60-hour week. To the extent that availability to work long and particular hours makes the difference between getting a promotion or seeing one’s career stagnate, women are disadvantaged.

And this disadvantage is reinforced in a vicious circle. Imagine a household where both members of a male–female couple have similarly demanding jobs. One partner’s career is likely to be prioritized if a grandparent is hospitalized or a child’s babysitter is sick. If the past history of employer pay-setting practices that disadvantage women has led to an already-existing gender wage gap for this couple, it can be seen as “rational” for this couple to prioritize the male’s career. This perpetuates the expectation that it always makes sense for women to shoulder the majority of domestic work, and further exacerbates the gender wage gap.

Female-dominated professions pay less, but it’s a chicken-and-egg phenomenon

Many women do go into low-paying female-dominated industries. Home health aides, for example, are much more likely to be women. But research suggests that women are making a logical choice, given existing constraints . This is because they will likely not see a significant pay boost if they try to buck convention and enter male-dominated occupations. Exceptions certainly exist, particularly in the civil service or in unionized workplaces (Anderson, Hegewisch, and Hayes 2015). However, if women in female-dominated occupations were to go into male-dominated occupations, they would often have similar or lower expected wages as compared with their female counterparts in female-dominated occupations (Pitts 2002). Thus, many women going into female-dominated occupations are actually situating themselves to earn higher wages. These choices thereby maximize their wages (Pitts 2002). This holds true for all categories of women except for the most educated, who are more likely to earn more in a male profession than a female profession. There is also evidence that if it becomes more lucrative for women to move into male-dominated professions, women will do exactly this (Pitts 2002). In short, occupational choice is heavily influenced by existing constraints based on gender and pay-setting across occupations.

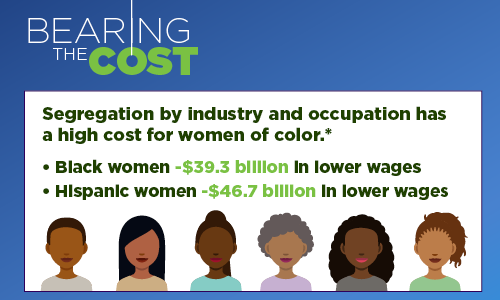

To make matters worse, when women increasingly enter a field, the average pay in that field tends to decline, relative to other fields. Levanon, England, and Allison (2009) found that when more women entered an industry, the relative pay of that industry 10 years later was lower. Specifically, they found evidence of devaluation—meaning the proportion of women in an occupation impacts the pay for that industry because work done by women is devalued.

Computer programming is an example of a field that has shifted from being a very mixed profession, often associated with secretarial work in the past, to being a lucrative, male-dominated profession (Miller 2016; Oldenziel 1999). While computer programming has evolved into a more technically demanding occupation in recent decades, there is no skills-based reason why the field needed to become such a male-dominated profession. When men flooded the field, pay went up. In contrast, when women became park rangers, pay in that field went down (Miller 2016).

Further compounding this problem is that many professions where pay is set too low by market forces, but which clearly provide enormous social benefits when done well, are female-dominated. Key examples range from home health workers who care for seniors, to teachers and child care workers who educate today’s children. If closing gender pay differences can help boost pay and professionalism in these key sectors, it would be a huge win for the economy and society.

The gender wage gap is real—and hurts women across the board. Too often it is assumed that this gap is not evidence of discrimination, but is instead a statistical artifact of failing to adjust for factors that could drive earnings differences between men and women. However, these factors—particularly occupational differences between women and men—are themselves affected by gender bias. Serious attempts to understand the gender wage gap should not include shifting the blame to women for not earning more. Rather, these attempts should examine where our economy provides unequal opportunities for women at every point of their education, training, and career choices.

— This paper was made possible by a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

— The authors wish to thank Josh Bivens, Barbara Gault, and Heidi Hartman for their helpful comments.

About the authors

Jessica Schieder joined EPI in 2015. As a research assistant, she supports the research of EPI’s economists on topics such as the labor market, wage trends, executive compensation, and inequality. Prior to joining EPI, Jessica worked at the Center for Effective Government (formerly OMB Watch) as a revenue and spending policies analyst, where she examined how budget and tax policy decisions impact working families. She holds a bachelor’s degree in international political economy from Georgetown University.

Elise Gould , senior economist, joined EPI in 2003. Her research areas include wages, poverty, economic mobility, and health care. She is a co-author of The State of Working America, 12th Edition . In the past, she has authored a chapter on health in The State of Working America 2008/09; co-authored a book on health insurance coverage in retirement; published in venues such as The Chronicle of Higher Education , Challenge Magazine , and Tax Notes; and written for academic journals including Health Economics , Health Affairs, Journal of Aging and Social Policy, Risk Management & Insurance Review, Environmental Health Perspectives , and International Journal of Health Services . She holds a master’s in public affairs from the University of Texas at Austin and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Anderson, Julie, Ariane Hegewisch, and Jeff Hayes 2015. The Union Advantage for Women . Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn 2016. The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations . National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 21913.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 2015. American Time Use Survey public data series. U.S. Census Bureau.

Corbett, Christianne, and Catherine Hill. 2015. Solving the Equation: The Variables for Women’s Success in Engineering and Computing . American Association of University Women (AAUW).

Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata (CPS ORG). 2011–2015. Survey conducted by the Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics [ machine-readable microdata file ]. U.S. Census Bureau.

Goldin, Claudia. 2014. “ A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter .” American Economic Review, vol. 104, no. 4, 1091–1119.

Hegewisch, Ariane, and Asha DuMonthier. 2016. The Gender Wage Gap: 2015; Earnings Differences by Race and Ethnicity . Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Herbert, Jennifer, and Deborah Stipek. 2005. “The Emergence of Gender Difference in Children’s Perceptions of Their Academic Competence.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology , vol. 26, no. 3, 276–295.

Hersch, Joni, and Leslie S. Stratton. 2002. “ Housework and Wages .” The Journal of Human Resources , vol. 37, no. 1, 217–229.

Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, Carolyn Buck Luce, Lisa J. Servon, Laura Sherbin, Peggy Shiller, Eytan Sosnovich, and Karen Sumberg. 2008. The Athena Factor: Reversing the Brain Drain in Science, Engineering, and Technology . Harvard Business Review.

Kroeger, Teresa, Tanyell Cooke, and Elise Gould. 2016. The Class of 2016: The Labor Market Is Still Far from Ideal for Young Graduates . Economic Policy Institute.

Landers, Renee M., James B. Rebitzer, and Lowell J. Taylor. 1996. “ Rat Race Redux: Adverse Selection in the Determination of Work Hours in Law Firms .” American Economic Review , vol. 86, no. 3, 329–348.

Levanon, Asaf, Paula England, and Paul Allison. 2009. “Occupational Feminization and Pay: Assessing Causal Dynamics Using 1950-2000 U.S. Census Data.” Social Forces, vol. 88, no. 2, 865–892.

Miller, Claire Cain. 2016. “As Women Take Over a Male-Dominated Field, the Pay Drops.” New York Times , March 18.

Oldenziel, Ruth. 1999. Making Technology Masculine: Men, Women, and Modern Machines in America, 1870-1945 . Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2015. The ABC of Gender Equality in Education: Aptitude, Behavior, Confidence .

Pitts, Melissa M. 2002. Why Choose Women’s Work If It Pays Less? A Structural Model of Occupational Choice. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Working Paper 2002-30.

Pope, Devin G., and Justin R. Sydnor. 2010. “ Geographic Variation in the Gender Differences in Test Scores .” Journal of Economic Perspectives , vol. 24, no. 2, 95–108.

See related work on Wages, Incomes, and Wealth | Women

See more work by Jessica Schieder and Elise Gould

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Professions and Organization

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Inequality, professions, and key challenges, can professions tackle the class ceiling, is the professional focus on culture a great mistake, global professional service firms and global inequality, professions and inequality, professions and inequality—towards an agenda for research and change.

- < Previous

Professions and inequality: Challenges, controversies, and opportunities

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Louise Ashley, Mehdi Boussebaa, Sam Friedman, Brooke Harrington, Stefan Heusinkveld, Stefanie Gustafsson, Daniel Muzio, Professions and inequality: Challenges, controversies, and opportunities, Journal of Professions and Organization , Volume 10, Issue 1, February 2023, Pages 80–98, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/joac014

- Permissions Icon Permissions

On the basis of the EGOS 2021 sub-plenary on ‘Professions and Inequality: Challenges, Controversies, and Opportunities’, the presenters and panellists wrote four short essays on the relationship between inequality as a grand challenge and professional occupations and organizations, their structures, practices, and strategies. Individually, these essays take an inquisitorial stance on extant understandings of (1) how professions may exacerbate existing inequalities and (2) how professions can be part of the solution and help tackle inequality as a grand challenge. Taken together, the discussion forum aims at advancing scholarly debates on inequality by showing how professions’ scholarship may critically interrogate extant understandings of inequality as a broad, multifaceted concept, whilst providing fruitful directions for research on inequality, their potential solutions, and the role and responsibilities of organization and management scholars.

Stefan Heusinkveld, Stefanie Gustafsson and Daniel Muzio

Inequality and social justice are long-standing concerns in academic research and public policy (e.g., Amis, Mair and Munir, 2020 ; Benschop, 2021 ; Zanoni et al., 2010 ). Research has persistently shown that unequally distributed access to resources and opportunities affects individual and collective well-being may diminish growth and productivity and undermine trust in key societal institutions ( Amis et al., 2018 ). This is particularly so in the contemporary political context where years of austerity have amplified social divisions and fuelled attacks on democratic and capitalist institutions. Inequality is one of the grand challenges of our times, and despite the progress made in both research and practice, it is considered the responsibility of scholars to not only address the many unanswered questions that remain but also to tackle inequality in society itself ( Amis et al., 2021 ; Benschop, 2021 ).

In this article, we argue that professional occupations and organizations , their structures, practices, and strategies are central to this agenda, both as potential barriers and also as solutions to inequality. We posit that research on professions is a critical resource for theorizing on inequality. Professions are based—by definition—on exclusionary structures and dynamics, seeking to restrict access to opportunities to a limited circle of eligible candidates in order to maintain their professional status ( Abbott, 1988 ). Substantial academic research in this field has shown that these closure regimes are gendered and racialized, disadvantaging women, ethnic minorities and individuals from less privileged backgrounds (e.g., Kay and Hagan, 1998 ; Kornberger, Carter and Ross-Smith, 2010 ; Tomlinson et al., 2013 , 2018 ; Carter, Spence and Muzio, 2015 ). Research on professions has also revealed that the most powerful professional services firms, deriving from a handful of largely Anglo-Saxon economies, are instrumental in maintaining and extending a capitalist and neo-liberal world order (e.g., Reed, 2018 ), while also contributing to the reproduction of neo-colonial practices and relationships (e.g., Boussebaa, 2015b ; Boussebaa and Faulconbridge, 2019 ). At its most extreme, studies show that professions have directly supported inequality by helping corporations and wealthy individuals to minimize, if not entirely elude their tax liabilities.

Yet, research has also evidenced how professional occupations and professional organizations can help to address inequality. Access to professional jobs and careers is an established route to upward social mobility. Women in many developed economies represent the majority of new entrants in professions, whilst black and minority ethnic individuals are often over-represented compared with their share of the population. Similarly, professions have an active role in the fight against inequality, by participating in the development and implementation of new products (micro-financing), organizations (social enterprises), regulations (new profit allocation rules for MNCs), and policies (international debt relief).

However, despite its value to advance scholarly debates on inequality, research on professions has not been systematically drawn upon as a fruitful conceptual resource and empirical context beyond occasional references and examples (e.g., Amis, Mair and Munir, 2020 ). This is remarkable not only given the field’s long-standing research tradition on inequality, but also given the importance of professions in maintaining societal inequality as well as their potential to offer impactful solutions. Indeed, professionals not only represent a substantial and growing portion of a country’s workforce ( Empson et al., 2015 ; Gorman, 2015 ) but are widely considered as key agents in the maintenance and change of institutions in contemporary society ( Scott, 2008 ; Suddaby and Viale, 2011 ; Muzio et al., 2013 ). Both characteristics also suggest a close proximity to the work and responsibilities of scholars as both teachers and researchers and privileged citizens. In other words, professions as a field of research, practice, and teaching are to be considered unique in their potential to further theorize on inequality more broadly and in promoting change.

To address these challenges, we invited the panellists of the EGOS 2021 sub-plenary on ‘Professions and Inequality’ to write a short essay on the relationship between inequality and professional occupations and organizations, drawing on insights from their research. In contrast to recent overviews of research on inequality and organizations, our contributors take a polemic and inquisitorial stance drawing on different levels of analysis and theoretical perspectives, thereby discovering differences and commonalities in scholarly views on how distinct professions relate to various aspects of inequality and to their potential solution. Firstly, in critically interrogating extant explanations of class inequalities in relation to professions, Sam Friedman shows how a primary focus on social mobility may obscure professions’ role in wider social patterns of inequality. He stresses the significance of enhancing transparency on socio-economic inequality in professions and firms, whilst also stimulating debates on how ‘talent’ is defined and rewarded. Secondly, Louise Ashley provides a comprehensive discussion of the possibilities and limitations of current scholarship and policies on inequality building on the work of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. She suggests alternative theoretical perspectives to rethink radical change in the current system of financial capitalism. In his essay, Mehdi Boussebaa also argues for radical change in limiting the (re)production of global inequalities by professional service firms (PSFs). He particularly emphasizes the role of professionals in the Global South to engage in cultural and economic resistance. Finally, Brooke Harrington ’s analysis shows how professions’ betrayal of their social contract in advancing the common good forms a critical basis for profound inequalities in contemporary society. In response, she advocates normative grassroots changes by advancing the fiduciary model that guides professionals’ understanding of their raison d’être. Together, as we will argue in the concluding part of this article, these contributions show the richness and value of research on professions in addressing unanswered questions and theorizing on inequality in management and organization studies while considering the role and responsibilities of organizational scholars in relation to the topic of inequality in their work.

Sam Friedman

In this essay, I reflect on the relationship between professions and class inequality, and specifically inequities in the professional workplace that flow from people’s social class origins. I first argue that the conventional sociological approach to social mobility is limited in two key ways; first, it fails to interrogate how rates of mobility vary across professions and, second, it tends to conceptualize social mobility as only an issue of occupational access rather than also pivotally career progression . I then show how recent studies from across sociology, social psychology and management have begun to remedy these issues, showing both how some professions are much more open than others to those from disadvantaged backgrounds and that those from working-class backgrounds often face significant class-origin pay gaps and ceilings within the professions. I then explore the potential mechanisms driving these class inequalities in career progression, both the ‘supply-side’ resources and dispositions that those privileged backgrounds tend to bring into the workplace and the ‘demand-side’ processes of cultural matching and intra-occupational sorting that means they are often more highly rewarded in their careers. I then explain that despite the growing evidence of class inequality in the workplace, professions themselves have been slow to take action. Only in the UK is a class starting to appear on the organizational agendas of professional employers, with a range of sectors starting to routinely collect data on the class origins of their staff and, in the case of firms of like KPMG, PWC, and the BBC, publicly commit to increasing the representation of senior managers from working-class backgrounds. While I argue that such moves should be welcomed, I conclude by cautioning that organizational social mobility agendas are restricted by a narrow focus on equality of opportunity and this can act to obscure how professions are implicated in wider societal patterns of class inequality. A more productive approach, I therefore suggest, would be for the ‘class agenda’ in the professions to focus not just on mobility but more broadly on class or socio-economic inequality—using the blueprint of the ‘Socioeconomic Duty’ set out in the UK Equality Act 2010.

The long shadow of class origin

Traditionally, the main point of entry into the subject of class in the professional workplace has been the study of social mobility—where ‘the professions’ are normally grouped together with managerial occupations to constitute a large, aggregate, socio-economic class ( Goldthorpe, Llewellyn and Payne, 1980 ). Using this framework, sociological analyses of class mobility have consistently demonstrated the unequal opportunity chances that exist in modern capitalist societies—usually measured by comparing the absolute and relative rates of mobility between a person’s class of origin (in terms of parental occupation) and their class of destination (in terms of own occupation) within a set of socio-economic classes 1 ( Breen, 2004 ). Yet in recent years a growing body of research has demonstrated that this conventional approach only provides a limited understanding of how class origin shapes inequality in professional career outcomes.

First, grouping all professions together obscures the fact that social mobility often varies substantially between professions ( Macmillan, Tyler and Vigoles, 2015 ; Stromme and Hansen, 2017 ). For example, in the UK, only 6% of doctors are from working-class backgrounds (meaning their main breadwinning parent did a routine or manual occupation) whereas the figure among engineers is considerably higher at 22% ( Friedman and Laurison, 2019 ).

Second, this dominant lens has meant that the conceptualization of social mobility has largely been tied to the idea of occupational access—who gets in rather than who gets on . Yet recent studies have shown that even when those from working-class backgrounds are successful in entering professional occupations, they go on to receive significantly lower incomes on average than their privileged colleagues. Such a class-origin pay gap has now been documented in a range of national contexts, including Britain, the USA, Canada, France, Norway, Sweden and Australia ( Hansen, 2001 ; Dinovitzer, 2011 ; Mastekaasa, 2011 ; Torche, 2011 ; Hällsten, 2013 ; Falcon and Bataille, 2018 ; Friedman and Laurison, 2019 ). While some studies attribute this inequality to fine-grained differences in educational attainment ( Hällsten, 2013 ; Torche, 2018 ), other studies find that class pay gaps remain substantial even after adjusting for class-origin differences in education, demographics, work location, occupational sorting and supposedly ‘meritocratic’ measures of ‘human capital’ such as experience, training and hours worked ( Hansen, 2001 ; Ljunggren, 2016 ; Falcon and Bataille, 2018 ; Friedman and Laurison, 2019 ).

Recently scholars have deepened this literature on class-origin pay gaps by investigating the mechanisms underlying this inequality. Here most have begun with the observation that class-origin income gaps are not necessarily driven by those from working-class backgrounds earning less for doing the same work (that is, for doing jobs at the same level, same company and same department) but more that they are less likely reach the most senior or lucrative positions—i.e., they face a ‘class ceiling’ ( Toft, 2019 ; Toft and Friedman, 2020 ; Ingram and Joohyun, 2022 ).

Some have attributed this vertical segregation less to the nature of professions themselves and more to ‘supply-side’ factors. For example, a range of studies have underlined how the careers of those from privileged-class backgrounds tend to be propelled by the inherited economic and social capital they bring into the workplace, and the overconfident, narcissistic, rule-breaking and entitled self-beliefs they exhibit once there ( Cote, 2011 ; Cote et al., 2021 ; Hansen and Toft, 2021 ). Fang and Tilcsuk (2022) have recently argued that another key mechanism is that people from upper-class origins tend to opt for professions with greater autonomy such as economics, which tend to be higher-paying, whereas their working-class counterparts tend to opt for more prosocial and less lucrative areas such as nursing and social work.

Yet significantly for this essay, there are also many scholars who attribute the class ceiling to ‘demand-side’ factors—i.e., to the structure, culture and systems of hiring and progression within professions ( Ingram and Allen, 2019 ). In particular, this work has identified two key mechanisms; cultural matching and intra-occupational sorting. First, drawing on Bourdeiusian theory, many have demonstrated that recruitment and progression processes at the most prestigious and lucrative professional employers tend to favour the already-privileged ( Cook, Faulconbridge and Muzio, 2012 ; Spence et al., 2017a ; Giazitzoglu and Muzio, 2021 ). For example, examining US professional service firms, Rivera (2016) shows that, first, top firms eliminate nearly every applicant who did not attend an elite college or university. They then put applicants through a series of ‘informal’ recruitment activities, such as cocktail parties and mixers, that are generally uncomfortable and unfamiliar to those from working-class backgrounds. Finally, when formal interviews happen, selectors often eschew formal criteria and evaluate candidates more on how at ease they seem, whether they build rapport in the interview, and whether they share common interests. Rivera describes this process as ‘cultural matching’ ( Rivera, 2016 ).

In a UK context, Ashley and Empson (2013) have found similar dynamics among elite firms operating in law, accountancy and banking—particularly those situated in the City (of London). In particular, they highlight how recruiters routinely misrecognize as ‘talent’ classed performances of ‘cultural display’. For example, recruiters seek a ‘polished’ appearance, strong debating skills and a confident manner, traits they argue can be closely traced back to middle-class upbringings.

Second, in my own work with Daniel Laurison ( Friedman and Laurison, 2019 ; Friedman, 2022 ), where we use mixed methods to compare class ceiling effects within the UK civil service, a national television broadcaster and a multinational accountancy firm, we find that a key mechanism across all firms is a distinct pattern of intra-occupational sorting. Specifically, we show that those from advantaged class backgrounds tend to both sort into, and are more readily rewarded within, work areas or departments characterised by heightened ‘knowledge ambiguity’ such as television commissioning, financial advisory and government policy work ( Alvesson, 2001 ; Ashley and Empson, 2013 ). In these areas, the success of the ‘final ‘product’ is often impossible to foretell, and therefore the knowledge and expertise of the professional tend to be particularly uncertain. What is used to plug this, our analysis suggests, is a certain performance or image of competence that is rooted in the embodied cultural capital (modes of comportment, self-presentation and aesthetic style) inculcated via a privileged-class background. Significantly, these work areas or departments also tend to be of higher status and afford more opportunities for progression to the most senior positions. In contrast, we find that those from working-class backgrounds tend to explicitly sort out of such knowledge-ambiguous areas and instead opt for, and progress quicker, in more technical (but less propulsive) work areas such as operational delivery where they perceive the skillset to be more transparent.

These various demand-side studies are significant because they suggest that professions do not just reflect existing class inequalities but, in certain important ways, can actively exacerbate their impact.

Can professions be part of the solution?

Despite the growing evidence base on class pay gaps and class ceilings, efforts to address such inequalities within the professions lag behind, particularly in comparison to gender and ethnicity. Indeed, in most countries, class or socio-economic background remain entirely absent from the organisational agendas of professional employers ( The Council of Europe, 2022 ). Only in the UK are there potential tentative grounds for optimism. Here, in recent years, discussions of the class have become commonplace across a range of professional sectors and a range of actions are beginning to take place.

For example, there is now a widespread collection of workforce data on class or socio-economic background—using a common methodology (see Social Mobility Commission, 2021 ). This has allowed employers to understand their internal class composition, class pay gap and class ceiling, but also to see how the class backgrounds of their staff intersect with other characteristics such as race and gender. Such advances are already generating insights. For example, recent work in the UK civil service has identified that women from working-class backgrounds often face a distinct double disadvantage in career progression ( Social Mobility Commission, 2021 ).

The collection of workforce data is also increasingly allowing firms and organizations to benchmark against others in their profession. This has led to growing recognition that positive change in removing barriers largely requires collective responsibility and collaborative action across a profession. Indeed, firms across the accountancy, legal, engineering and financial services professions in the UK have all begun to work in concert to tackle class-origin gaps in career progression (see, e.g., Bridge Group, 2018 , 2020 ). Indeed, many firms have taken the important step of publishing socio-economic data publicly and some, such as KPMG, PWC, and the BBC, have even gone further, setting targets to increase the representation of those from working-class backgrounds at partner or senior management level ( Timmins, 2021 ; Simpson, 2022 ).

Beyond data, though, there is much more than professional employers must do to be part of the solution. The most significant of these is to grapple with the most significant driver of class ceilings; how ‘talent’ and ‘merit’ is defined and rewarded in the workplace. The key point in the literature on this is that the identification of merit is often intertwined with the way merit is performed (in terms of classed self-presentation and arbitrary behavioural codes) and who the decision-makers are whose job it is to recognize and reward these attributes. This is a thorny issue that is hard to tackle, especially where there is contestation within professions about what merit or skill looks like. Yet I would argue that professions must embrace this contestation, to critically interrogate the ‘objective’ measures of merit they rely on, to think carefully about whether such measures have a performed dimension, and to what extent they can be reliably connected to demonstrable output or performance. The goal here should surely be more transparent and widely agreed upon idea of what merit looks like in the professional workplace.

There are certainly, then, some concrete ways that professions are tackling class inequality or may do in the near future. But at the same time, I want to conclude by registering an important caveat to the celebratory narratives that often surround professional employers’ social mobility strategies. This is simply that the interventions they envisage may be a necessary part of tackling class inequality in professions, but they are certainly not sufficient . This, fundamentally, is because they only address one aspect of class inequality; namely, equality of opportunity and the fair allocation of rewards within the workplace. But as a range of sociologists has argued ( Lawler, 2017 ; Littler, 2018 ) this narrow focus on social mobility is not, and cannot be, the solution to class inequality. Indeed, as Ingram and Gamsu (2022) have recently pointed out, discussions about the relationship between professions and inequality must engage with the work professionals do , as well as who they are . Here they point to the paradox that the professional firms taking class most seriously, internally, are arguably the same ones accentuating class inequalities in the work they do externally . For example, over the last 30 years, The Big Four professional service firms have been both involved in, and profited from, the privatization and outsourcing of public services and state-owned companies in the UK. This, Ingram and Gamsu (2022) argue, has had direct knock-on effects on people in working-class jobs—including the erosion of working conditions, lowering rates of pay, the loss of defined benefit pensions and increasing casualization of employment (see also Hermann and Flecker, 2013 ). Similarly, as Ashley (2021) notes, many professions are directly implicated in driving the kind of high pay that has contributed so profoundly to growing income inequality in many Western countries.

In this way, it is clearly important to recognise that organizational social mobility agendas sometimes act as a form of cultural legitimation, allowing professional employers to align themselves with egalitarian values while obscuring their role in perpetrating class inequalities in society more broadly. A more productive approach, I would suggest, would be for the ‘class agenda’ in the professions to focus not just on social mobility but more broadly on class or socio-economic inequality. Indeed, there is already a potential blueprint for this in the UK in the form of the ‘Socioeconomic Duty’ contained within the Equality Act 2010. This section both speaks to the equality of opportunity in making class origin a protected characteristic (meaning it would be against the law to discriminate against someone on the basis of class origin), but also goes significantly further, requiring government and all public bodies to have ‘due regard for ‘reducing inequalities of outcome, especially as they relate to socio-economic disadvantage’. While successive governments have declined to bring this section into effect, perhaps it is high time the professions stepped in to fill the gap.

Louise Ashley

Inequality is a pressing problem for economies throughout the world and professions, especially ‘elite’ PSFs, are closely implicated. This partly relates to their role in supporting a form of financialised capitalism which helps concentrate wealth, though entrenched organizational systems and structures play a role. Compensation practices are important as very high pay for professionals in ‘top jobs’ contributes to significant income inequalities in the UK ( Amis et al., 2018 : see also IFS, 2022 ). Elite PSFs are also the sites of institutionalized practices which contribute to the marginalization of under-represented groups. One recent study found that in leading UK law firms over 50% of partners are white, male and privately educated, compared to 7% of the population who attend fee-paying schools ( Bridge Group, 2020 ). Collectively, these statistics contradict the narrative of merit historically deployed by professions to help justify high pay. As these imbalances have been exposed this has contributed to reputational pressures and many PSFs have felt compelled to act, most recently by making efforts to open access on the basis of social class, which is my main focus here ( Ashley, 2021, 2022 ; Cabinet Office, 2010 ; SMC, 2015 ).

Since elite professions both reflect and reproduce steep status hierarchies in society at large, this might seem an encouraging development, still more so if, as a result, elite PSFs can help tackle wider societal inequalities via interventions aimed at promoting upward social mobility. This is certainly how organizational leaders position this agenda, and as a way in which professions can live up to their professed commitment to merit, but these claims should be treated with caution. Elsewhere, I have argued that interventions introduced by elite PSFs aimed at addressing classed barriers to entry provide an illusion of change which legitimates and thus sustains the wider inequalities these firms help to create ( Ashley, 2021, 2022 ). In what follows, I describe a closely related challenge, to suggest the conceptual tools currently used most often to understand and address these inequalities (tools, I should say, I have regularly used myself) are inadequate for the task, both as they reflect the wider ‘cultural turn’ in sociology, and more specifically, borrow from the work of Bourdieu (e.g., 1977 , 1984 , 1990 ).

This might seem surprising given that Bourdieu is often considered the preeminent sociologist of the twentieth century. To provide some context, while Marx believed class was determined by our relationship to the means of production, and by economic wealth or cash , and Weber underlined how credentials could improve life chances for individuals and collective mobility for discrete status groups, Bourdieu’s emphasis was on culture . He argued that an individual’s position in the social field is determined by their portfolio of economic, social and cultural capital, along with the socio-cultural outlook comprising habitus. The latter relates to inherited and internalized dispositions which influence actors to unconsciously enact practices and behaviours which ensure (dis)advantage is reproduced. This framework has been widely used to explore who gets ahead in elite professions and how (e.g., Friedman and Laurison, 2019 ; Sommerlad, 2011 ), and to show how aspirant professionals from less advantaged backgrounds are blocked from entry, or are sorted (and sort themselves) into specific roles, on the basis of their portfolio of capital and perceived cultural ‘fit’ (e.g., Cook, Faulconbridge and Muzio, 2012 ; Ashley and Empson, 2013 , 2017 ; Rivera, 2016 ). This body of work is not only academic but, as part of more engaged sociology, has helped generate wider awareness of the profession’s problem with class, and provided a foundation from which elite firms and other organisations have designed solutions, as I will show.

If accurate analysis of a problem is necessary for effective action, this may seem a positive development. However, in what follows, I make two main points. First, I argue that Bourdieu’s core concepts have been selectively applied in practical interventions, contributing to their superficial effect. Second, I raise a more fundamental challenge, as while Bourdieu theorized inequalities within capitalism he did not theorise capitalism itself, and one result is that he offered no meaningful theory of change ( Riley, 2017 ). In the next section, I provide some brief contextual information before expanding on these arguments and considering the conceptual tools which might work better instead.

Classed inequalities and professional culture

During the 1990s and into the early 2000s, social class largely disappeared from the policy agenda in the UK, as successive administrations championed a new age of meritocracy where education rather than background would determine opportunities. Towards the end of that period, it became increasingly evident that this optimism was misplaced. An important moment for the professions was the release of the Cabinet Office publication in 2010: ‘ Unleashing Aspiration; The Final Report of the Panel on Fair Access to the Professions .’ This reported that younger professionals (born in 1970) typically grew up in a family with an income 27% above that of the average family, compared with 17% for older professionals (born in 1958), and that, despite formal recruitment techniques and the expansion of higher education over the past 30 years, elite professions had become increasingly closed, stifling opportunities for upward social mobility. In 2012, the Conservative government set up the Social Mobility Commission (SMC) to help report on and stimulate change and this was followed by a raft of related reports and studies many of which used frameworks provided by Bourdieu. Two examples include studies I led for the SMC in 2015 and 2016 exploring barriers to access in law and accountancy, and investment banking, which explained how recruitment and selection processes offer systematic advantages to young people from more privileged backgrounds with the ‘right’ portfolio of cultural and social capital, whose prior socialisation offered them confidence that they ‘fit.’

Efforts to address this situation are part of a ‘social mobility industry’ in the UK ( Payne, 2017 ), one arm of which is represented by increasing numbers of not-for-profit and charitable bodies such as the Social Mobility Foundation (SMF), UpReach and The Sutton Trust. These organisations work with leading professional and financial service firms as partners and funders to identify talented young people from under-represented backgrounds and offer them training in soft skills, along with mentoring and internships. The immediate aims are to extend participants’ social networks (social capital), help them acquire behaviours and mannerisms often summarized within the professions as ‘polish’ (cultural capital), and provide them with opportunities to familiarize themselves with professional environments (attending most obviously to habitus). Thousands of young people have now taken part, supported by leading names such as investment bank J.P Morgan, big four accountancy firms such as EY and KPMG, and magic circle law firms, such as Allen & Overy and Freshfields.

For individual participants, these programmes are often considered life-changing ( Ashley, 2022 ), yet overall, there is limited evidence of significantly improved outcomes for under-represented groups (e.g., IFS, 2021 ). This takes me to the first of my two main critiques, which is to suggest that the limited impact of social mobility programmes can be partly explained as a Bourdieusian framework has been selectively applied.

To expand on this point, Bourdieu explained how everyday practices can only be understood by using all three of his interlocking conceptual tools: habitus, capital and field. However, as applied to professional practice aimed at opening access, the focus has predominantly been on correcting assumed deficits in individual portfolios of capital and much less on exclusionary structures that define the field. This contributes to a cosmetic effect as interventions of this type can only assist a talented few, and only if they become quite similar to existing elites, yet assimilation of this type is difficult for many and impossible for some, including because, as Reay (2017) points out, class is not a ‘cloak’ that can be taken on and off. It is no coincidence perhaps that this approach sits comfortably within the wider diversity agenda, currently the dominant approach to workplace inequalities in the professions as elsewhere, but one which has a similarly superficial effect. This may seem paradoxical since the diversity agenda was forged in the very neoliberalism that Bourdieu railed against. However, as just one example of where they overlap, diversity situates ‘unconscious bias’ as the primary explanation for workplace inequalities, while Bourdieu also argued that everyday practices enacted by individuals originate in unconscious beliefs and habits. While starting from different ideological positions, both make the locus of power diffuse, and position unfair outcomes as simultaneously everybody and thus nobody’s fault, to obscure what or who we are struggling against and undermine our capacity to mount a moral critique of the current social order.

There is, though, a second and more comprehensive critique, starting from the position that while Bourdieu’s politics were radical, his sociology is not ( Riley, 2017 ). Criticism of this type has generally been launched from a Marxist perspective and the many points of (dis)connection between the two are far beyond the scope of this piece. However, while Bourdieu sought to bridge the structure/agency divide, Wright (2009 , p. 106) argues that using his framework, social position can be interpreted as largely the outcome of individual actions rather than structural conditions and further, that: ‘the rich are rich because they have favourable attributes, the poor because they lack them.’ While Bourdieu underlines the relativity of social position, this differs from Weberian and Marxist approaches which show in more depth how classed inequalities are relational , are sustained by the (sometimes conscious) exercise of power, and that successful struggles would necessarily threaten the privileges of those in advantaged positions. In contrast, and as Wright (2009) points out, Bourdieu failed to theorize a systemic causal connection between who is rich and who is poor, or properly address the workings of power and thus his work can support a position suggesting that inequalities can be reduced simply by ‘improving’ the culture and education of disadvantaged groups.

It is then especially significant that it is not Marx or Weber who inform the profession’s efforts at reducing inequalities, but the work of Bourdieu, or that these efforts are also regularly positioned by firm leaders as in some sense ‘win-win,’ for both talented young people and elite PSFs. In practice, where opportunities are not expanding in absolute terms, progress would require weakening the privilege of existing elites, but there has been little sign of that. These failures may however explain precisely why a definition of ‘class as culture’ is so attractive to professional elites, as where the problem of inequality is defined as cultural domination, and where the class is considered a subjective identity rather than an objective ‘fact,’ this plays into the hands of current elites. First, because related interventions offer useful reputational capital to existing elites, with no requirement that they should share their material rewards or give anything up. Second, because underlying structural inequalities inherent to our current model of financialized capitalism, within which elite PSFs are closely implicated, are conveniently overlooked in favour of the mistaken (but legitimized) belief that cultural change can deliver progress without radical adjustments to the system itself. In short, as it has filtered into practice, Bourdieu’s conceptual blind spot with respect to the structural relations of capitalism has arguably helped protect the interests of existing professional elites and thus sustain related material inequalities of income and wealth.

Against this broad backdrop, Burawoy (2019 , p. 196) notes that intellectuals who promote Bourdieu’s ideas (after all, ‘professionals’ too) have become: ‘a vehicle for the reproduction of capitalism by suppressing the very idea of capitalism and failing to project an alternative beyond capitalism’. Of course, related failures do not mean Bourdieu’s framework should be abandoned but to properly understand and address inequalities of any type we must get to their root cause. In the current context, this could include further efforts to expose how elite professionals maintain their privilege via power relations which operate at the expense of people who are poor, and how the ‘solutions’ elite PSFs implement might sustain the very problem of inequality they help to create. As Wright suggests (2009), demystification of this sort requires a holistic approach, combining not only Weber with Bourdieu but also returning to Karl Marx, whose insights on exploitation and inequality are less fashionable perhaps but remain relevant, nevertheless.

Mehdi Boussebaa

This essay addresses this forum’s two core questions—how the professions exacerbate inequality and whether can they be part of the solution—by focusing on the issue of global inequality. By ‘global inequality’, I am referring to the socio-economic unevenness that exists between the Global North (aka the ‘developed world’) and the Global South (aka the ‘developing world’). This unevenness is rooted in Western colonialism and, despite decolonization, remains a core feature of the world economy. I will argue, first, that the professions exacerbate such inequalities through the ‘so-called global professional service firms’ (hereafter GPSFs) to which they have given rise. Second, I will argue that these organizations are unlikely to be part of the solution, although they may inadvertently engender conditions to that end. Given the scarcity of studies on the topic, my argument is inevitably tentative and exploratory, but, I hope, will catalyse future research.

GPSFs as agents of global inequality

It is now well established that the rise of GPSFs has been one the most significant changes in the contemporary landscape of the professions ( Faulconbridge and Muzio, 2012 ) and that these firms have become ‘global’ in large part to serve multinational enterprises (MNEs) across the globe ( Beaverstock, Smith and Taylor, 1999 ; Greenwood et al., 2010 ). What has tended to be overlooked, however, is that MNE clients, the largest of which have until recently been almost exclusively headquartered in the Global North, have been a major agent of global inequality (see, e.g., Petras and Veltmeyer, 2007 ; Smith, 2016 ). This is perhaps most visible in the global production networks (GPNs) that they control. These networks of course provide some economic benefits to countries in the Global South but, as Buckley and Strange (2015 : 244) put it,

the (increased) profits from the dispersed value-chain activities will accrue to the shareholders of the MNEs. The overall impact on income in the host emerging economies will be limited, while the MNEs’ shareholders (predominantly in the advanced economies) will generally profit from these overseas ventures in the long term […]. Global inequalities in the distribution of income may thus be exacerbated as a result.

In-depth and historically informed analyses of GPNs and multinational enterprise more broadly are far more critical (e.g., Smith, 2016 ; Suwandi, 2019 ). They reveal extreme forms of labour exploitation and dire social and environmental consequences in the Global South—the Rana Plaza disaster springs to mind here. Importantly, these analyses enable us to see the ‘big picture’ by contextualizing global inequalities within a long-term process that has been central to the development of capitalism, namely, colonialism. This, then, helps in seeing how the activities of MNEs result in not just large-scale transfers of income from the South to the North but also continuing patterns of unequal exchange and uneven development in the world economy. GPSFs may be deeply implicated in this process given their raison d’être is to serve MNEs.

Indeed, since the 1990s, GPSFs have been offering a growing suite of offshore outsourcing services (see, e.g., Silver and Daly, 2007 ), i.e., services specifically designed to enhance Northern MNEs’ ability to access and exploit the vast low-wage labour pools of the Global South. Related services are also offered to Southern supplier firms seeking to participate in this process, often to the detriment of domestic workforces. For instance, Munir et al.’s (2018) study of GPNs in the clothing industry reveals the role of US consultants in shaping the thinking and practices of Pakistani suppliers towards forms of management that ‘protected the interests of western branded apparel companies and consumers, but did not necessarily serve the interests of workers’ (p. 561).

Additionally, GPSFs such as accounting firms may be exacerbating global inequality through the tax services which they offer to MNEs, among other clients. A growing body of literature suggests accountancies may be facilitating tax evasion on a massive scale ( Sikka and Hampton, 2005 ; Sikka and Willmott, 2013 ; see also Hearson, 2021 ; Seabrooke and Wigan, 2022 ). Such malpractice is a drain on the resources of most societies, but Southern countries are particularly vulnerable, not least because they lack the resources to understand and combat Northern tax avoidance strategies ( Sikka and Willmott, 2013 ; see also Hearson, 2021 ). The literature suggests that GPSFs may be enabling complex tax avoidance schemes that result in the Global South being stripped of US$100 billion of tax revenue each year. Such revenue, as Sikka and Willmott (2013) put it, ‘could be used to provide, sanitation, security, clean water, education, healthcare, pensions and social infrastructure to improve the quality of life for millions of people’ (p. 420).

Interestingly, GPSFs also appear to be reproducing North-South inequalities within their own organizational boundaries. Northern professionals generally ‘own’ the most lucrative client relationships and capture the bulk of the profits earned from the global projects which they deliver on behalf of Northern MNEs ( Boussebaa, 2015a ; Rose and Hinings, 1999 ). This unequal distribution of income is exacerbated by the tremendous cross-national fee-rate differentials that exist within GPSFs—Northern professionals generally command fees that are far higher than those that accrue to colleagues in the Global South. This also often results in the former capturing large chunks of the profits generated through projects led by the latter. Boussebaa (2009 : 843) illustrates this drawing on an interview with a London-based manager working within the consulting division of a major American GPSF. The manager commented that he alone earned more than 23% of the total earned from a large project run by his firm’s Polish office: ‘In Poland, my project [a project for which assistance from the UK was requested] was £3.2 million and I think I accounted for about £750,000 of that £3.2 million – just one resource’. 2

These internal dynamics suggest that, as I have argued elsewhere, GPSFs may be ‘institutionalizing internal hierarchies that mirror the long-standing core/periphery hierarchy of the world capitalist system’ ( Boussebaa, 2017 : 234). Such hierarchies are also reflected in and indeed (in part) enabled by organizational arrangements that generally protect, prioritise and advance the interests of Northern professionals. Note, for instance, how the top leadership teams of GPSFs are mostly, if not exclusively, composed of professionals based in the West ( Boussebaa, 2015a , b)—typically, ‘white, heterosexual, middle-class males’ ( Empson et al., 2015 : 14). Note also how GPSFs have developed global knowledge management systems that, among other things, serve to promote and export Northern knowledge—generally at great cost to Southern colleagues ( Boussebaa, Sturdy and Morgan, 2014 ).

Aside from client services and intra-organizational processes, GPSFs reproduce global inequality by shaping the rules governing international trade and investment in ways that align with their priorities. Arnold’s (2005) study of globalization in the accounting sector is particularly useful here. It reveals significant efforts by Anglo-American accounting firms (together with Northern industry lobbies), supported by the World Trade Organization, to use international trade agreements towards the creation of a global market for their services. The study also shows how the legal and institutional arrangements produced by such efforts can ‘trump domestic laws to the disadvantage of developing nations by pre-empting laws designed to protect indigenous accounting industries, and by instituting transparency rules [… that give accounting firms] access to and a voice in the rulemaking deliberations of smaller nations’ ( Arnold, 2005 : 323). Further insights on such neo-colonial dynamics can be found in various sociological studies examining sustained efforts by networks of Northern actors, including professionals, to reshape Southern societies in congruence with the goals and preferences of the former (e.g., Dezalay and Garth, 2002 ; Halliday and Carruthers, 2009 ; see also Boussebaa, 2022 ; Boussebaa and Faulconbridge, 2019 ).

In sum, it is fair to suggest that the professions exacerbate global inequality through the global firms to which they have given rise. Of course, the set of arguments put forward above provides a schematic representation of global inequality and the role of GPSFs in its reproduction. I do not mean to imply that the North-South divide is static or that the Global South, including Southern professionals, has no agency to change the status quo. The resurgence of China and India as major economic powers and the associated rise of large professional service firms in those countries is telling in that regard (a point I return to below). But such cases are exceptions and, as Lees’ (2021 : 85) recent systematic evaluation of the evidence on the question reveals, ‘North–South divisions have persisted […] despite decades of change within the international system’. My argument in this essay is that GPSFs contribute significantly to this persistence.

Prospects for addressing global inequality

The discussion above provides, in part, an answer to the second question motivating this forum: can the professions be part of the solution? The segment of the professions I have examined in this essay, GPSFs, lives off MNEs and the global inequality produced in that relationship; it is therefore difficult to imagine it being part of the solution. A GPSF working towards global equality would undermine its very raison d’etre and bring about its own demise.

Indeed, GPSFs not only reproduce global inequality but also actively work to hide it from view by propagating a sanitised narrative of ‘globalization’. In this narrative, colonialism—corporate-driven or state-managed—is a thing of the past and it, therefore, makes little sense to speak of a North-South divide today. As Keniche Ohmae, a former managing director of McKinsey, notoriously argued, we now live in a ‘borderless world’ and leading MNEs are no longer home-centric organizations seeking to appropriate the labour, markets and resources of the Global South. On the contrary, such organizations have become or are en route to becoming, ‘stateless’ and are a source of progress and development across the globe. Likewise, we are led to believe that GPSFs have themselves metamorphosed into post-colonial entities working to the benefit of humanity as a whole. In this way, the inequalities discussed above are glossed over.

That said, the process of GPSFs becoming global may also carry within it seeds for change towards reduced global inequality. Specialist studies of colonialism reveal that colonial projects have always been met with resistance—not just military but also economic and cultural. As Edward Said once put it in relation to European colonialism, ‘it was the case nearly everywhere in the non-European world that the coming of the white man brought forth some sort of resistance ( Said, 1994 : xii).’ It is worth quoting him at more length:

Along with armed resistance […], there also went considerable efforts in cultural resistance almost everywhere, the assertions of nationalist identities, and, in the political realm, the creation of associations and parties whose common goal was self-determination and national independence. Never was it the case that the imperial encounter pitted an active Western intruder against a supine or inert non-Western native […] and in the overwhelming majority of cases, the resistance finally won out ( Said, 1994 : xii).

In the contemporary period, the intrusion of Northern MNEs and GPSFs, with the support of Northern governments and Northern-centric multilateral organizations, has itself been met with resistance. Note how, for example, Anglo-American corporate law firms are presently banned from opening offices in India, in part due to fears that, as Krishnan (2010 : 60) put it, ‘liberalizing the legal services sector would inevitably lead to India’s legal system being controlled by modern-day Western colonialists – something a country that suffered from centuries of imperial rule can never permit.’ But resistance may also occur in less obvious ways, through, for instance, Southern professionals setting up their own firms and becoming competitors. Chinese and Indian professionals have been particularly successful in this regard, but recent years have also seen the emergence of indigenous firms in economically less powerful nation-states. One example is Morocco-headquartered Bennani & Associés, which now has offices across various parts of North, West and Central Africa.

Needless to say, the rise of these firms requires critical scrutiny. On the one hand, they may be seen as a manifestation of resistance and move towards more equality in the world system. And, in some instances, Southern governments have played a determining role in that regard, as seen in the case of China, which has actively encouraged the development of indigenous firms as part of a wider state-managed project of economic emancipation and growth. On the other hand, it is possible that indigenous firms may simply be serving the interests of dominant Northern GPSFs, providing them with local advice and networks towards further expansion into the Global South (see, e.g., Dezalay and Garth, 2012 ). All the same, the growth of these firms suggests that Southern professionals, with appropriate support from Southern states, may well have it within their means in the 21st century to help tackle the global inequality that GPSFs have contributed to extending into the 20th century and beyond.

In sum, GPSFs seem to play a crucial role in the reproduction of global inequality and a solution to the problem is more likely to come from the Global South than the firms themselves or indeed the wider system of professions which has given rise to them. I, therefore, conclude this essay with a call for further research into not only the role of GPSFs (and Southern collaborators) in reproducing North-South inequalities but also, importantly, that played by Southern professionals in addressing the problem.

Brooke Harrington

The two motivating questions of this forum—how do professions contribute to inequality and how can they be part of the solution—can be answered with a single statement: it depends on whose behalf the professions are working. Thus, this essay offers two theses about the relationship of professions to inequality. The first is that professions exacerbate inequality by using their expertise to profit at their clients’ expense—as in Gürses and Danışman’s study of physicians ( 2021 )—or by amplifying the fortunes and power of an elite clientele, such as the high-net-worth individuals served by wealth managers running the offshore financial system ( Harrington 2015 , 2017 ). Thesis two is that the professions can undo some of the damage they have done in exacerbating inequality by returning to their original responsibility: to serve the public interest with their expertise ( Adams, 2017 ). The remainder of this essay will elaborate on these points.

Experts exacerbating inequality

For centuries, societies have given a small group of experts’ special privileges, such as authority and autonomy, in return for their pledge to use those skills for the advancement of the common good. The concept of a common good generally includes the notion of equal opportunity, such as via equitable access to professional services like education and medical care—along with equal opportunity to enter the professions themselves ( Dobbin, 2009 ). Enforcing this commitment is the purpose of professional associations and state licensing boards; they establish standards for quality and ethics, as well as for sanctions on misconduct. Professions have been entrusted with self-governance on the understanding—usually made explicit in their codes of conduct—that practitioners would use their powers exclusively in the public interest ( Adams, 2017 ).

However, a series of recent events represent profound betrayals of that ancient social contract. As this essay is being written, some of the most high-status professionals in the world are being sanctioned for their role in the most recent Russian invasion of Ukraine. Non-military efforts to counter the invasion have highlighted the roles of attorneys, accountants and bankers—primarily in the UK, the US and key European jurisdictions, such as Switzerland and Monaco—in helping Russian oligarchs amass the vast stores of offshore wealth and proceeds of corruption underwriting the war ( Croft 2022 ; Gross 2022 ).