Human-Centered Change and Innovation

Innovation, change and transformation thought leadership, lovingly curated by braden kelley, design thinking vs. traditional problem-solving, which approach fosters better business innovation.

GUEST POST from Chateau G Pato

In today’s rapidly evolving business landscape, innovation is the key driver of growth and success. To stay ahead of the competition, businesses must adopt an approach that not only solves problems effectively but also incorporates human-centered thinking and fosters creativity. This thought leadership article explores the two prominent problem-solving methodologies – Design Thinking and Traditional Problem-Solving – and delves into their effectiveness in driving business innovation. Through the analysis of two case studies, we examine how each approach can impact an organization’s ability to innovate and ultimately thrive in a competitive market.

1. Design Thinking: Embracing Empathy and Creativity:

Design Thinking is a customer-centric approach that places emphasis on empathy, active listening, and iterative problem-solving. By gaining a deep understanding of end-users’ needs, aspirations, and pain points, businesses can create innovative solutions that truly resonate with their target audience. This methodology comprises five key stages: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test. Let’s explore a case study that illustrates the power of Design Thinking in fostering business innovation.

Case Study 1: Airbnb’s Transformation:

When Airbnb realized their business model needed a refresh, they turned to Design Thinking to reimagine the experience for users. By empathizing with both hosts and guests, Airbnb identified pain points, such as low trust levels and inconsistent property quality. They defined the core problem and developed innovative solutions through multiple brainstorming sessions. This iterative approach led to the creation of user-friendly features such as verified user profiles, secure booking processes, and an enhanced rating system. As a result, Airbnb disrupted the hospitality industry, revolutionizing how people book accommodations, and became a global success story.

2. Traditional Problem-Solving: Analytical and Linear Thinking:

Traditional problem-solving methods often follow a logical, linear approach. These methods rely on analyzing the problem, identifying potential solutions, and implementing the most viable option. While this approach has its merits, it can sometimes lack the human-centered approach essential for driving innovation. To delve deeper into the impact of traditional problem-solving on business innovation, let’s examine another case study.

Case Study 2: Blockbuster vs. Netflix:

Blockbuster, once an industry giant, relied on traditional problem-solving techniques. Despite being highly skilled at analyzing data and trends, Blockbuster failed to tap into their customers’ unmet needs. As the digital revolution occurred, Netflix recognized an opportunity to disrupt the traditional video rental business. Netflix utilized Design Thinking principles early on, empathizing with customers and understanding that convenience and personalized recommendations were paramount. Through their innovative technology and business model, Netflix transformed the way people consume media and eventually replaced Blockbuster.

Design Thinking and Traditional Problem-Solving are both valuable methodologies for business problem-solving. However, when it comes to fostering better business innovation, Design Thinking stands out as an approach that encourages human-centered thinking, empathy, and creativity. By incorporating Design Thinking principles into their problem-solving processes, organizations can develop innovative solutions that address the unmet needs of their customers. The case studies of Airbnb and Netflix demonstrate how adopting a Design Thinking approach can lead to significant business success, disrupting industries while putting the user experience at the forefront. As businesses continue to face dynamic challenges, embracing Design Thinking can empower them to drive continuous innovation and secure competitive advantage in the modern era.

SPECIAL BONUS: The very best change planners use a visual, collaborative approach to create their deliverables. A methodology and tools like those in Change Planning Toolkit ™ can empower anyone to become great change planners themselves.

Image credit: Pexels

Related posts:

- How to Determine if Your Problem is Worth Solving

- What is Design Thinking?

- Applying Design Thinking for Innovation and Problem Solving

- Design Thinking for Non-Designers

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Hey! You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

The Common Flaw of All Problem-Solving Models

W e suspect that every reader of this newsletter has been steeped in articles and classes on a myriad of problem-solving techniques. We have all been exposed to techniques such as:

- GROW Model (Goal, Reality, Obstacles/Options, Way Forward)

- Decision Analysis

- Divide & Conquer

- Brainstorming

- Etc, etc, etc… ad nauseum

Unfortunately, abundant data doesn’t necessarily help leaders develop insight or see the interrelatedness of the information.

For the benefit of those who played hooky or who don’t like to read, the underlying message of problem-solving workshops and best practice articles is, ironically, that:

1, Most models do not deliver on the promise of actually solving organizational problems. 2. And the reason for this is usually not due to “operator error.”

… But I Love Models!

Although problem-solving models can be elegant in theory, they are often less helpful in practice. The linear, equation-like approach to problem solving offers hard-edge clarity and precision that is very comforting. However, with complex problems (those involving humans), models typically result in little or no lasting change to the problem.

On the plus side, the problem-solving processes have a strong focus on data gathering. Information on all the parts and pieces of a problem, and occasionally on all of the internal/external forces that impact the problem, is usually a key part of any problem-solving process.

Unfortunately, abundant data doesn’t necessarily help leaders develop insight or see the interrelatedness of the information. In fact, sometimes it results in information overload and actually inhibits problem solving. But as the gambler says, “The game may be crooked but it’s the only game in town.”

At the most basic level, problem solving in an organization is about:

- Making quality decisions

- Executing effectively on those decisions

- Oh yeah, and solutions should reflect an understanding of all of the variables.

No sweat, right? Unfortunately, what seems so simple in theory is anything but in practice.

The Monkey Wrench of Problem Solving

A key condition that makes this seemingly simple and logical process of organizational problem solving so difficult is complexity.

Pardon the geeky definition, but “Complexity refers to interesting patterns and structures that arise from the dynamic interaction of independent elements”—and people are a major element!

In enterprises of any significant size, complexity is alive and well. In fact, complex organizational problems can be so dynamic and adaptive, they can feel alive. They can also feel like they are teetering on the edge of chaos and apt to spin out of control at any moment!

But We Are the Best and Brightest

There is no doubt about the amazing talent that rises to leadership positions in competitive organizations. We have the honor of working with many of the best and brightest daily.

The problem is that even the best leaders have little time for the reflection and analysis that good problem solving requires. And many have only been exposed to linear problem-solving techniques. Good stuff, but applying linear problem-solving tools to complex, dynamic problems will have you drooling on your BlackBerry® and stuttering in no time.

There is no easy fix for complex, dynamic problems. All the problems with easy fixes get taken care of lower down on the organizational chain. Only the most persistent, vexing, and seemingly irresolvable challenges land on your desk—that’s why you get the big bucks.

But don’t despair.

Six Steps to Resolving Complex Dynamic Problems

People can solve complex and dynamic business problems. So, how do they do it? Our favorite approach is using the tools and methodology of systems thinking. Oh no, another model? But I thought you said…

Taking a systemic approach to problem solving offers a practical and pragmatic way to begin to:

- Understand the value of exploring the contributing factors of a problem

- Assess potential intended and unintended consequences

- Redefine the problem based on a closer look at all of the contributing factors

- Select solutions that can deliver the greatest degree of change

Go through the six steps and judge for yourself whether this might provide a breakthrough in your problem solving approach. One suggestion as you contemplate the value of these steps: remember, systems thinking is a team sport. This approach blossoms from multiple perspectives.

Step One: Select a Problem Determine if the problem is complex, dynamic, and interconnected, or straight-forward and linear.* You can use the following five criteria with your team to determine if a situation fits the definition of a complex, systemic issue:

1. It has a pattern. There is a clear history of this problem happening over time, sometimes to the point of acceptance.

2. It has no easy answer and seems to impact a number of other issues and/or departments. No

_________ * A problem can be very complicated, with a fundamentally high level of intricacies—such as determining the tensile strength of the steel required to build a tank—and not have the kind of dynamic complexity that makes it a systemic issue. The techniques of lean manufacturing are superb for resolving linear problems, even if the linear problems are highly complicated!

one wants to take on the problem because it seems too daunting.

3. People are involved. The success of a process depends on human input or judgment.

4. Fixes have been tried but the problem persists. You may have tried to fix the problem or implemented workarounds, but the problem remains and as a result of the “fix,” new problems may have been created.

5. It is multi-dimensional. The issue or problem may involve several functions or possibly customers or suppliers.

Step Two: Identify Contribution Factors

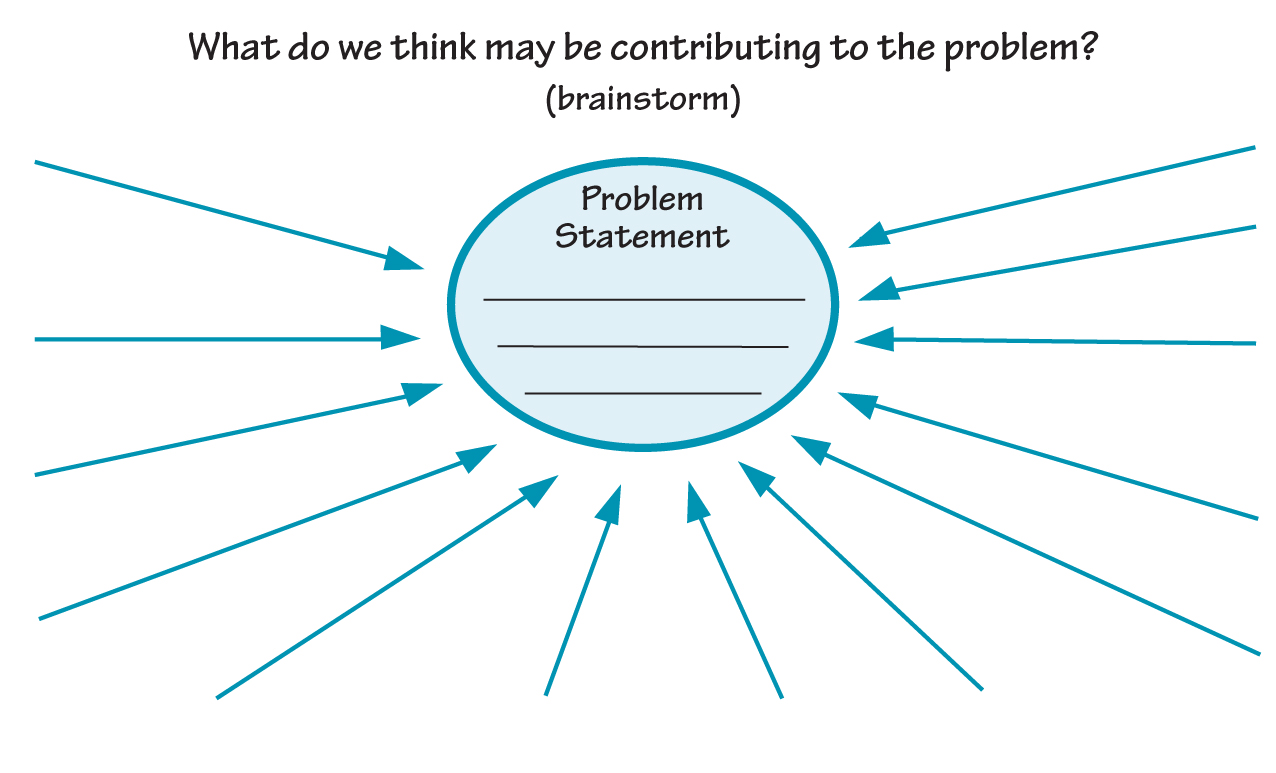

Every problem has some things that you and your team believe are reinforcing, driving, or contributing to the issue in some fashion. The “Systemic Curiosity Worksheet” offers a simple format to use to record the team’s input.

SYSTEMIC CURIOSITY WORKSHEET

The “Systemic Curiosity Worksheet” offers a simple format to use to record the team’s beliefs on the things that are reinforcing, driving, or contributing to the problem.

Step Three: Review the Problem

Based on the identification of the factors contributing to the problem, review the problem statement and determine if it needs to be restated. The perspectives shared in the discussion about contributing factors frequently lead to a fuller and more complete understanding of the dimensions of the issues to be addressed.

Step Four: Establish Solutions

From a review and discussion of the contributing factors, and the potentially restated problem statement, work with the team to identify at least three ways to solve (influence) the problem.

Step Five: Frame Implications

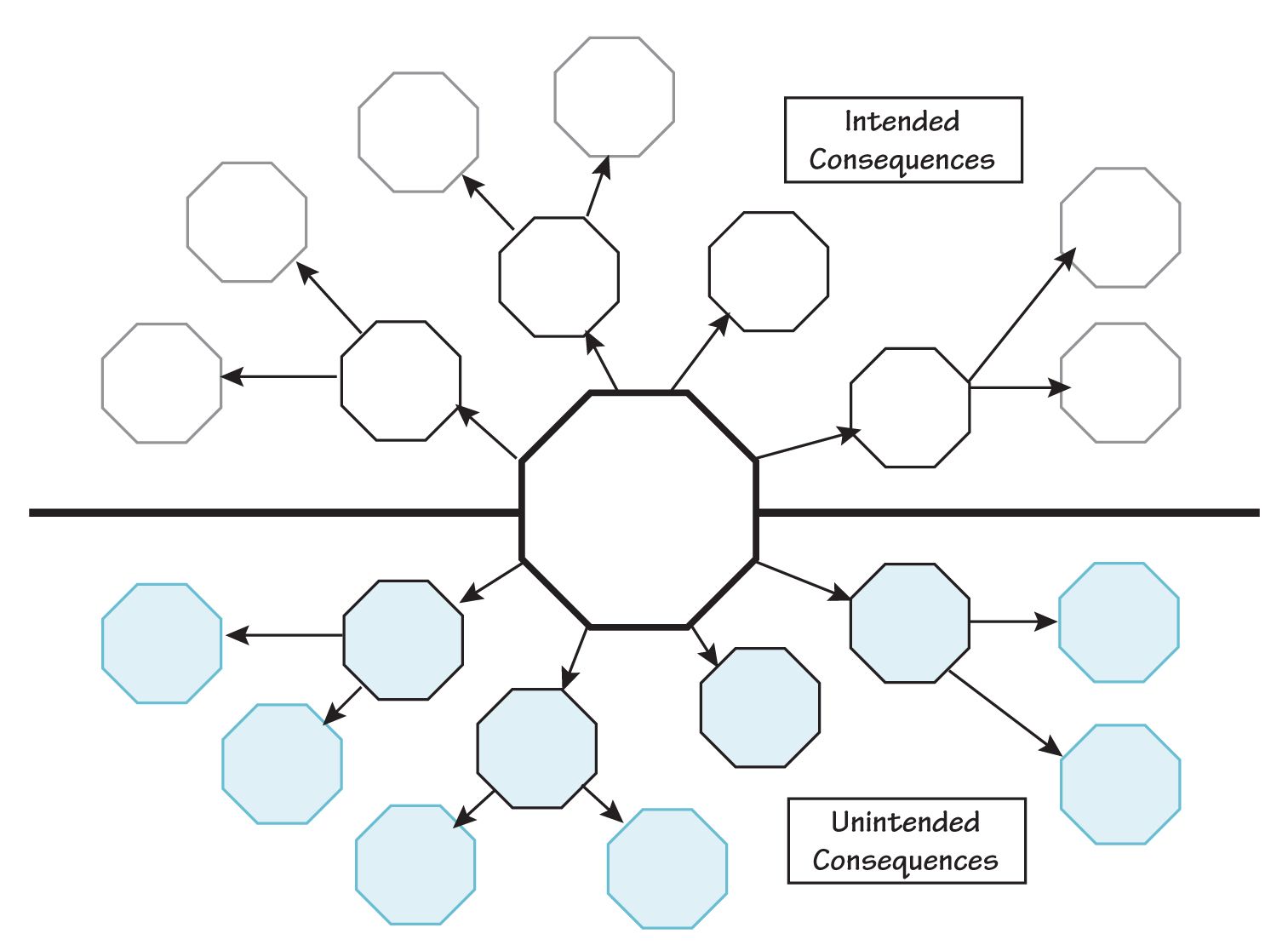

Determine what the consequences could be of implementing each of the chosen solutions. Describe both intended and unintended consequences, outlining what could happen that the solution is designed to produce, as well as what could happen that is unplanned.

The “Implications Wheel” worksheet is a handy visual to use.

IMPLICATIONS WHEEL

Use the “Implications Wheel” to determine what the intended and unintended consequences could be of implementing each of the chosen solutions.

Step Six: Select Solutions

With a more thorough understanding of the system that is producing the current problem, as well as having identified and tested a number of potential “right answers,” you and your team are now able to select the solutions that can deliver the highest degree of change.

Bonus Outcome

In addition to resolving complex-dynamic problems, this six-step process has the added benefit of:

Encouraging team interaction

► which generates shared team understanding

► which helps develop significant insights around the chosen issue that were not previously apparent.

Paul R. Plotczyk is president of Work Systems Affiliates International, Inc., a leadership and organization development consulting firm. For more than 25 years, he has helped a wide range of clients address tough challenges. Paul has taught and lectured at universities and professional conferences in the United States and Europe. He has co-authored a number of publications, including Best Practices in Executing Projects, Best Practices in Teams, Best Practices in Tools, and Best Practices in Process Improvement.

Related Articles

Learning and leading through the badlands.

We hear a lot about complexity in the business world today — specifically, that increasing complexity is making…

All Methods Are Wrong. Some Methods Are Useful.

Interest in systems concepts is reviving and broadening. However, the sheer size of the field poses a dilemma…

A Pioneer on the Next Frontier: An Interview with Jay Forrester

DIANE CORY: This first question is from a manager at Xerox: “How can I help overcome the common perception…

Integrating Systems Thinking and Design Thinking

As readers of this newsletter are aware, systems thinking is evolving as an alternative to the old paradigms.

Sign up to stay in the loop

Receive updates of new articles and save your favorites..

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Password * Enter Password Confirm Password

Is the Traditional Problem-Solving Process Obsolete?

- Jean Scheid

- Categories : Resource management

- Tags : Project management

It’s Almost Perfect

All traditional problem solving processes were pretty much the same and in the end, project managers would often settle with a solution that worked best—most of these solutions weren’t perfect, however.

During a project, a problem was defined and analyzed, and a solution (perhaps several) were chosen to “fix” the problem. The solution that offered the most promise to project teams was usually selected and implemented. If the solution was ineffective, only after it was implemented was the traditional problem-solving process started again .

The basics of problem solving and fixes, in the age of obsolete project management, were much like a chef developing a recipe. The taste test ruled and if an element was missing, the chef kept adding until the recipe achieved the desired outcome.

Are the traditional ways of solving problems lost in the world of today’s project management, or are they delicately hidden within the various project management methodologies we utilize today?

Image Credit ( Free Digital Photos )

Hide and Seek

Initially, most problems aren’t clear or defined. Managers and teams find hidden flaws and seek ways to improve the errors made. In fact, the traditional problem-solving process is a much longer avenue than those seen in methodologies like 5S, Lean, or even Six Sigma.

While researching this topic of traditional problem solving, I found that most problem-solving experts offered between ten and twelve steps in a traditional approach. These steps more commonly started with who should be the decision maker to defining the problem to choosing the “best” fix and then monitoring the fix to see if it did indeed correct the problem.

Perhaps for new project managers, these traditional ways of problem solving are effective, but they are hardly ever efficient. With Six Sigma phases that include DMAIC, DMADV or DMEDI , you can tell by these acronyms alone that you’ve got five steps in each of these processes, and tucked inside these famous Six Sigma acronyms are standards for identifying a problem, repairing it, and realizing a defect-free outcome.

Traditional vs. New

If we look at traditional problem-solving processes suggested by Master Class Management , where twelve steps are offered, they include:

- Who is the person who will be the decision maker?

- Why is the problem present?

- Where is the problem?

- Why should it be called a “problem?”

- What is the cause of the problem?

- How large is the problem?

- Is the problem urgent?

- If the problem didn’t exist, what would be the ideal outcome?

- What are possible solutions to the problem?

- Pick the best or agreed-upon solution.

- Plan for the problem fix and implement that fix.

- Monitor the fix to see if the problem was solved.

These twelve steps, while effective, can lengthen project finish times. What if instead, a Six Sigma process was utilized such as DMEDI wherein the problem solving process was considered throughout the project? Or, what if problems could be solved using an Agile Methodology?

Shortening the Problem Solving Cycle

One of the processes utilized in Six Sigma, DMEDI–or define, measure, explore, develop, and implement–has only five phases.

With DMEDI the problem-solving phase is completed long before the final phase, or the “implement” phase. While the implement phase means the project outcome is ready for market, in DMEDI, the Explore and Develop phases ensure, through project problem-solving controls, that concerns are addressed, analyzed, and fixed, and future fixes or improvements are developed prior to the Implement phase.

The phases of an Agile project are much the same where an iteration isn’t passed along until it’s totally complete; in Agile, done really does mean done . Some detriments to using more modern problem-solving techniques may be if the methodology is not utilized correctly or if a methodology doesn’t include a root cause analysis to identify problems during the project process.

Using a traditional problem-solving process is more than likely the best way for project management students and entry-level managers to grasp the basic knowledge of problem solving, but as technology and creativity continue to be inserted into projects, problem solving as a standalone management tool in today’s world of project management, is really not considered a best practice.

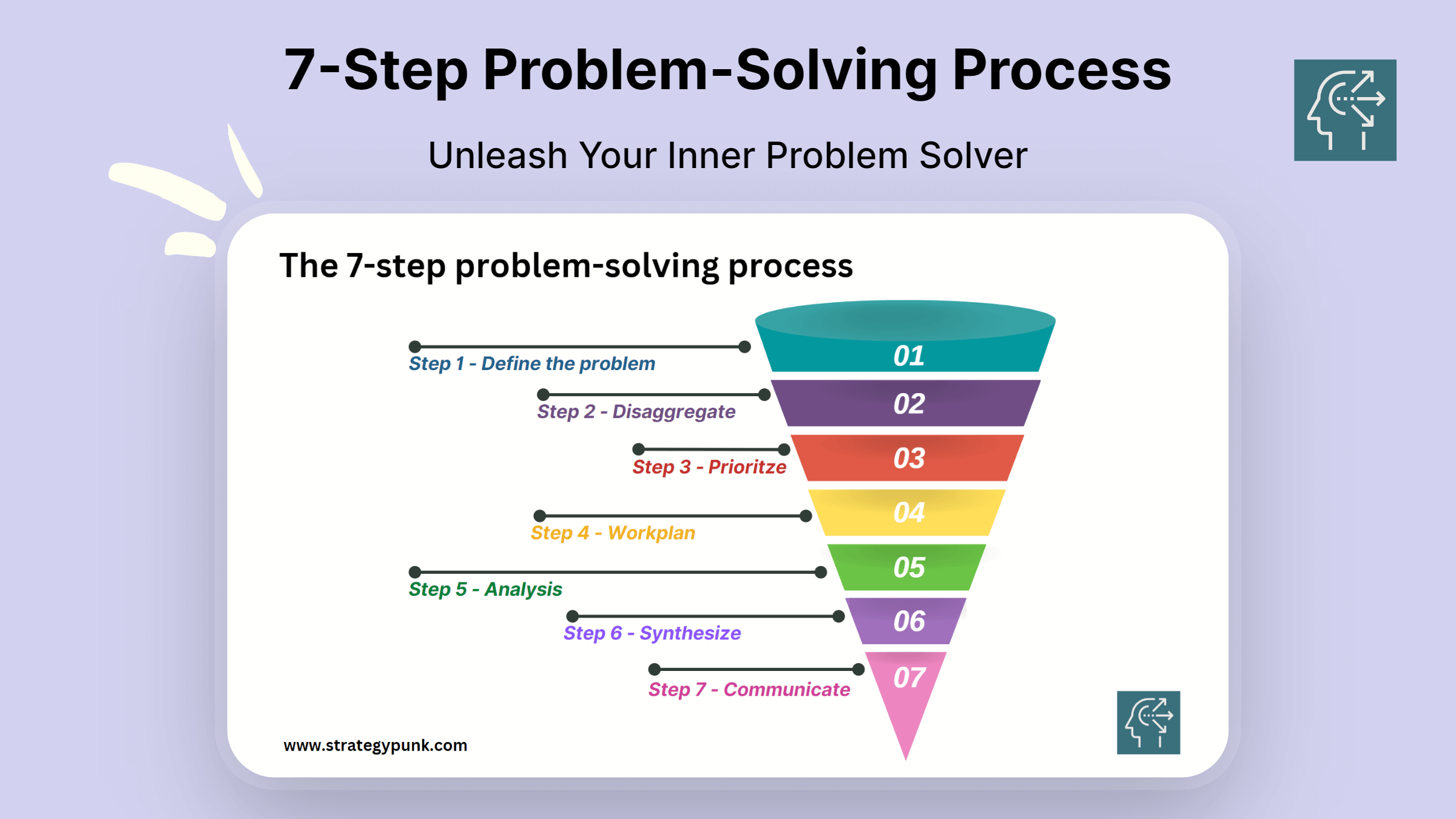

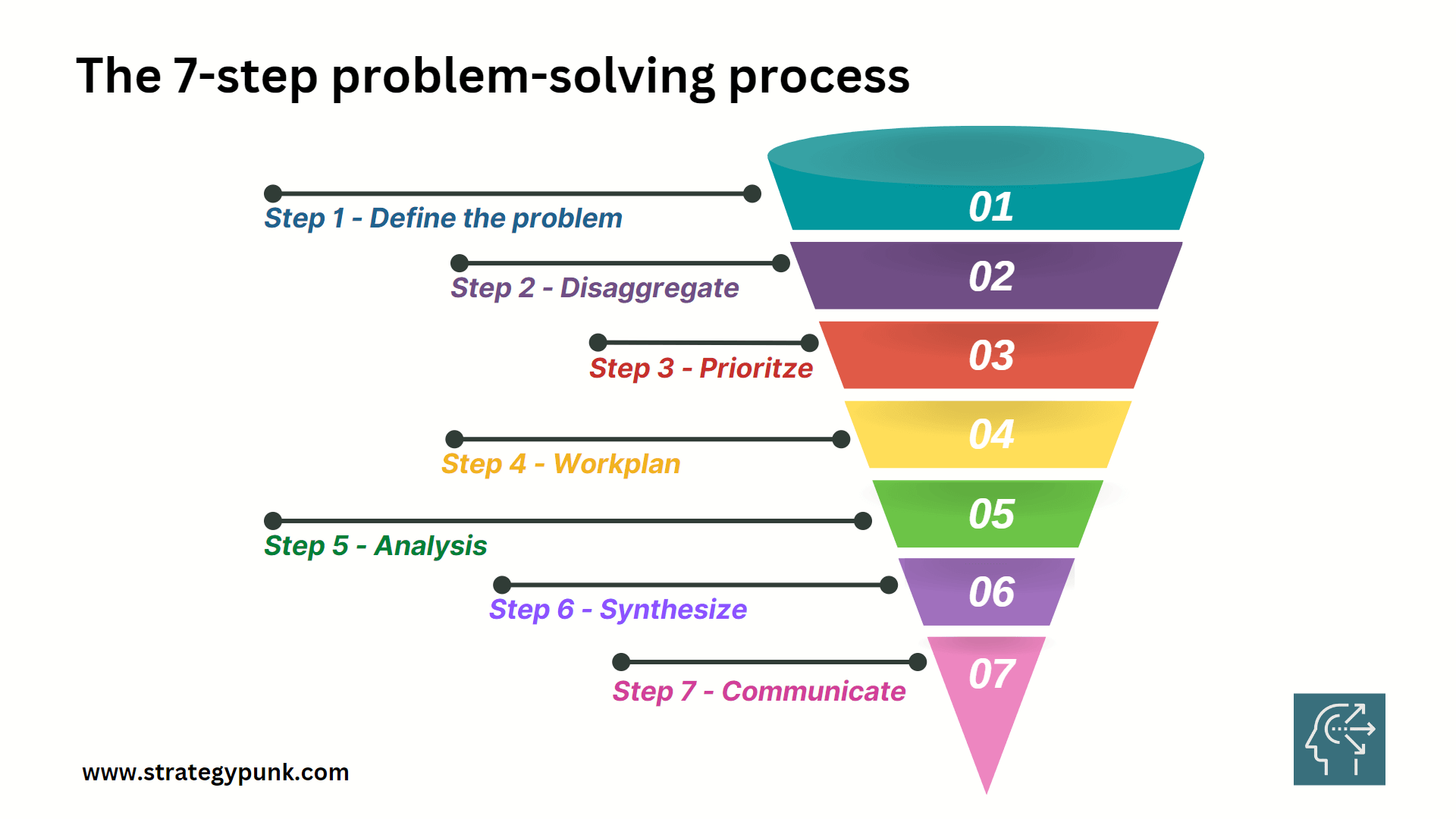

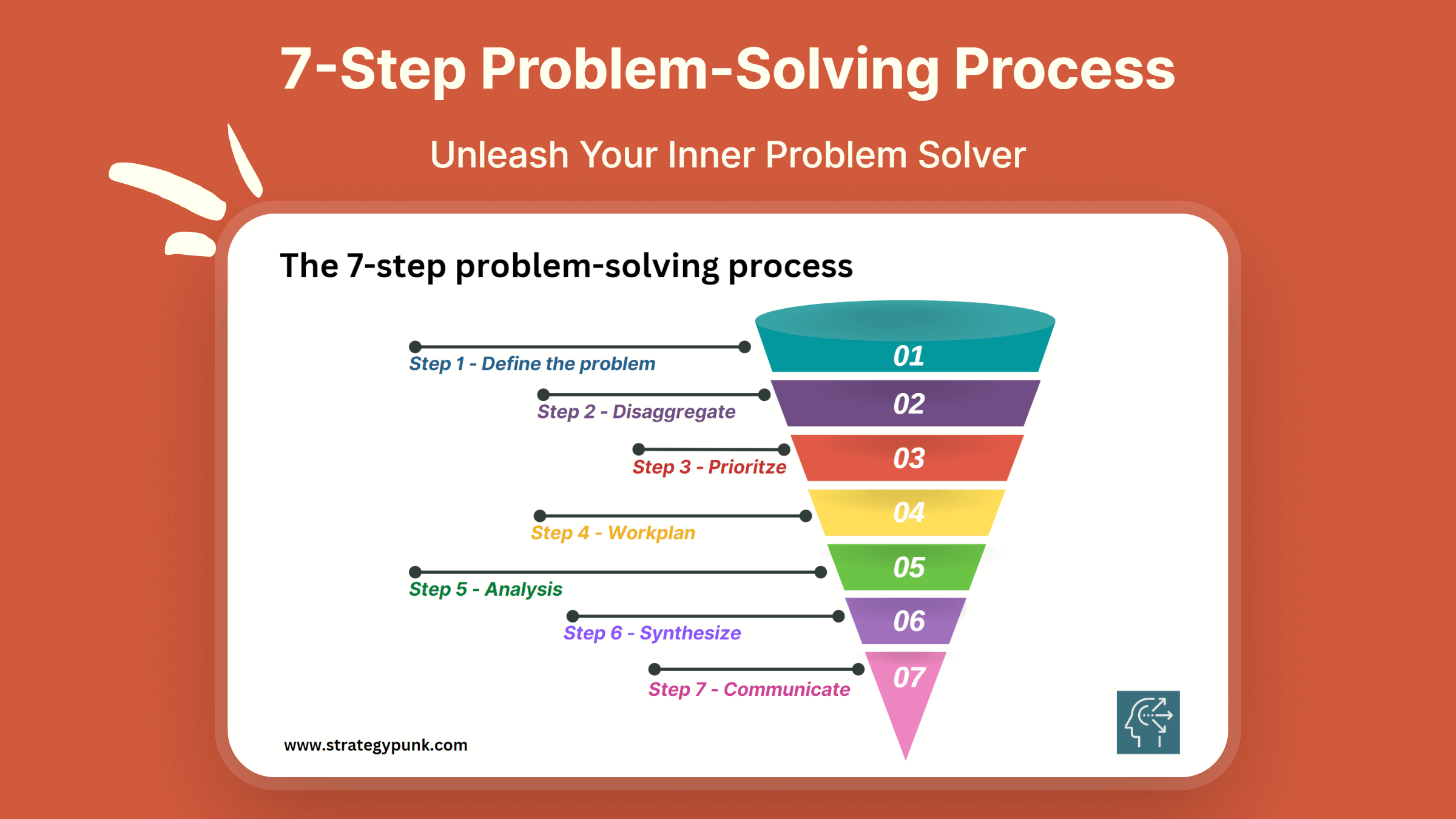

How to master the seven-step problem-solving process

In this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , Simon London speaks with Charles Conn, CEO of venture-capital firm Oxford Sciences Innovation, and McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin about the complexities of different problem-solving strategies.

Podcast transcript

Simon London: Hello, and welcome to this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , with me, Simon London. What’s the number-one skill you need to succeed professionally? Salesmanship, perhaps? Or a facility with statistics? Or maybe the ability to communicate crisply and clearly? Many would argue that at the very top of the list comes problem solving: that is, the ability to think through and come up with an optimal course of action to address any complex challenge—in business, in public policy, or indeed in life.

Looked at this way, it’s no surprise that McKinsey takes problem solving very seriously, testing for it during the recruiting process and then honing it, in McKinsey consultants, through immersion in a structured seven-step method. To discuss the art of problem solving, I sat down in California with McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin and also with Charles Conn. Charles is a former McKinsey partner, entrepreneur, executive, and coauthor of the book Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything [John Wiley & Sons, 2018].

Charles and Hugo, welcome to the podcast. Thank you for being here.

Hugo Sarrazin: Our pleasure.

Charles Conn: It’s terrific to be here.

Simon London: Problem solving is a really interesting piece of terminology. It could mean so many different things. I have a son who’s a teenage climber. They talk about solving problems. Climbing is problem solving. Charles, when you talk about problem solving, what are you talking about?

Charles Conn: For me, problem solving is the answer to the question “What should I do?” It’s interesting when there’s uncertainty and complexity, and when it’s meaningful because there are consequences. Your son’s climbing is a perfect example. There are consequences, and it’s complicated, and there’s uncertainty—can he make that grab? I think we can apply that same frame almost at any level. You can think about questions like “What town would I like to live in?” or “Should I put solar panels on my roof?”

You might think that’s a funny thing to apply problem solving to, but in my mind it’s not fundamentally different from business problem solving, which answers the question “What should my strategy be?” Or problem solving at the policy level: “How do we combat climate change?” “Should I support the local school bond?” I think these are all part and parcel of the same type of question, “What should I do?”

I’m a big fan of structured problem solving. By following steps, we can more clearly understand what problem it is we’re solving, what are the components of the problem that we’re solving, which components are the most important ones for us to pay attention to, which analytic techniques we should apply to those, and how we can synthesize what we’ve learned back into a compelling story. That’s all it is, at its heart.

I think sometimes when people think about seven steps, they assume that there’s a rigidity to this. That’s not it at all. It’s actually to give you the scope for creativity, which often doesn’t exist when your problem solving is muddled.

Simon London: You were just talking about the seven-step process. That’s what’s written down in the book, but it’s a very McKinsey process as well. Without getting too deep into the weeds, let’s go through the steps, one by one. You were just talking about problem definition as being a particularly important thing to get right first. That’s the first step. Hugo, tell us about that.

Hugo Sarrazin: It is surprising how often people jump past this step and make a bunch of assumptions. The most powerful thing is to step back and ask the basic questions—“What are we trying to solve? What are the constraints that exist? What are the dependencies?” Let’s make those explicit and really push the thinking and defining. At McKinsey, we spend an enormous amount of time in writing that little statement, and the statement, if you’re a logic purist, is great. You debate. “Is it an ‘or’? Is it an ‘and’? What’s the action verb?” Because all these specific words help you get to the heart of what matters.

Want to subscribe to The McKinsey Podcast ?

Simon London: So this is a concise problem statement.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah. It’s not like “Can we grow in Japan?” That’s interesting, but it is “What, specifically, are we trying to uncover in the growth of a product in Japan? Or a segment in Japan? Or a channel in Japan?” When you spend an enormous amount of time, in the first meeting of the different stakeholders, debating this and having different people put forward what they think the problem definition is, you realize that people have completely different views of why they’re here. That, to me, is the most important step.

Charles Conn: I would agree with that. For me, the problem context is critical. When we understand “What are the forces acting upon your decision maker? How quickly is the answer needed? With what precision is the answer needed? Are there areas that are off limits or areas where we would particularly like to find our solution? Is the decision maker open to exploring other areas?” then you not only become more efficient, and move toward what we call the critical path in problem solving, but you also make it so much more likely that you’re not going to waste your time or your decision maker’s time.

How often do especially bright young people run off with half of the idea about what the problem is and start collecting data and start building models—only to discover that they’ve really gone off half-cocked.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah.

Charles Conn: And in the wrong direction.

Simon London: OK. So step one—and there is a real art and a structure to it—is define the problem. Step two, Charles?

Charles Conn: My favorite step is step two, which is to use logic trees to disaggregate the problem. Every problem we’re solving has some complexity and some uncertainty in it. The only way that we can really get our team working on the problem is to take the problem apart into logical pieces.

What we find, of course, is that the way to disaggregate the problem often gives you an insight into the answer to the problem quite quickly. I love to do two or three different cuts at it, each one giving a bit of a different insight into what might be going wrong. By doing sensible disaggregations, using logic trees, we can figure out which parts of the problem we should be looking at, and we can assign those different parts to team members.

Simon London: What’s a good example of a logic tree on a sort of ratable problem?

Charles Conn: Maybe the easiest one is the classic profit tree. Almost in every business that I would take a look at, I would start with a profit or return-on-assets tree. In its simplest form, you have the components of revenue, which are price and quantity, and the components of cost, which are cost and quantity. Each of those can be broken out. Cost can be broken into variable cost and fixed cost. The components of price can be broken into what your pricing scheme is. That simple tree often provides insight into what’s going on in a business or what the difference is between that business and the competitors.

If we add the leg, which is “What’s the asset base or investment element?”—so profit divided by assets—then we can ask the question “Is the business using its investments sensibly?” whether that’s in stores or in manufacturing or in transportation assets. I hope we can see just how simple this is, even though we’re describing it in words.

When I went to work with Gordon Moore at the Moore Foundation, the problem that he asked us to look at was “How can we save Pacific salmon?” Now, that sounds like an impossible question, but it was amenable to precisely the same type of disaggregation and allowed us to organize what became a 15-year effort to improve the likelihood of good outcomes for Pacific salmon.

Simon London: Now, is there a danger that your logic tree can be impossibly large? This, I think, brings us onto the third step in the process, which is that you have to prioritize.

Charles Conn: Absolutely. The third step, which we also emphasize, along with good problem definition, is rigorous prioritization—we ask the questions “How important is this lever or this branch of the tree in the overall outcome that we seek to achieve? How much can I move that lever?” Obviously, we try and focus our efforts on ones that have a big impact on the problem and the ones that we have the ability to change. With salmon, ocean conditions turned out to be a big lever, but not one that we could adjust. We focused our attention on fish habitats and fish-harvesting practices, which were big levers that we could affect.

People spend a lot of time arguing about branches that are either not important or that none of us can change. We see it in the public square. When we deal with questions at the policy level—“Should you support the death penalty?” “How do we affect climate change?” “How can we uncover the causes and address homelessness?”—it’s even more important that we’re focusing on levers that are big and movable.

Would you like to learn more about our Strategy & Corporate Finance Practice ?

Simon London: Let’s move swiftly on to step four. You’ve defined your problem, you disaggregate it, you prioritize where you want to analyze—what you want to really look at hard. Then you got to the work plan. Now, what does that mean in practice?

Hugo Sarrazin: Depending on what you’ve prioritized, there are many things you could do. It could be breaking the work among the team members so that people have a clear piece of the work to do. It could be defining the specific analyses that need to get done and executed, and being clear on time lines. There’s always a level-one answer, there’s a level-two answer, there’s a level-three answer. Without being too flippant, I can solve any problem during a good dinner with wine. It won’t have a whole lot of backing.

Simon London: Not going to have a lot of depth to it.

Hugo Sarrazin: No, but it may be useful as a starting point. If the stakes are not that high, that could be OK. If it’s really high stakes, you may need level three and have the whole model validated in three different ways. You need to find a work plan that reflects the level of precision, the time frame you have, and the stakeholders you need to bring along in the exercise.

Charles Conn: I love the way you’ve described that, because, again, some people think of problem solving as a linear thing, but of course what’s critical is that it’s iterative. As you say, you can solve the problem in one day or even one hour.

Charles Conn: We encourage our teams everywhere to do that. We call it the one-day answer or the one-hour answer. In work planning, we’re always iterating. Every time you see a 50-page work plan that stretches out to three months, you know it’s wrong. It will be outmoded very quickly by that learning process that you described. Iterative problem solving is a critical part of this. Sometimes, people think work planning sounds dull, but it isn’t. It’s how we know what’s expected of us and when we need to deliver it and how we’re progressing toward the answer. It’s also the place where we can deal with biases. Bias is a feature of every human decision-making process. If we design our team interactions intelligently, we can avoid the worst sort of biases.

Simon London: Here we’re talking about cognitive biases primarily, right? It’s not that I’m biased against you because of your accent or something. These are the cognitive biases that behavioral sciences have shown we all carry around, things like anchoring, overoptimism—these kinds of things.

Both: Yeah.

Charles Conn: Availability bias is the one that I’m always alert to. You think you’ve seen the problem before, and therefore what’s available is your previous conception of it—and we have to be most careful about that. In any human setting, we also have to be careful about biases that are based on hierarchies, sometimes called sunflower bias. I’m sure, Hugo, with your teams, you make sure that the youngest team members speak first. Not the oldest team members, because it’s easy for people to look at who’s senior and alter their own creative approaches.

Hugo Sarrazin: It’s helpful, at that moment—if someone is asserting a point of view—to ask the question “This was true in what context?” You’re trying to apply something that worked in one context to a different one. That can be deadly if the context has changed, and that’s why organizations struggle to change. You promote all these people because they did something that worked well in the past, and then there’s a disruption in the industry, and they keep doing what got them promoted even though the context has changed.

Simon London: Right. Right.

Hugo Sarrazin: So it’s the same thing in problem solving.

Charles Conn: And it’s why diversity in our teams is so important. It’s one of the best things about the world that we’re in now. We’re likely to have people from different socioeconomic, ethnic, and national backgrounds, each of whom sees problems from a slightly different perspective. It is therefore much more likely that the team will uncover a truly creative and clever approach to problem solving.

Simon London: Let’s move on to step five. You’ve done your work plan. Now you’ve actually got to do the analysis. The thing that strikes me here is that the range of tools that we have at our disposal now, of course, is just huge, particularly with advances in computation, advanced analytics. There’s so many things that you can apply here. Just talk about the analysis stage. How do you pick the right tools?

Charles Conn: For me, the most important thing is that we start with simple heuristics and explanatory statistics before we go off and use the big-gun tools. We need to understand the shape and scope of our problem before we start applying these massive and complex analytical approaches.

Simon London: Would you agree with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: I agree. I think there are so many wonderful heuristics. You need to start there before you go deep into the modeling exercise. There’s an interesting dynamic that’s happening, though. In some cases, for some types of problems, it is even better to set yourself up to maximize your learning. Your problem-solving methodology is test and learn, test and learn, test and learn, and iterate. That is a heuristic in itself, the A/B testing that is used in many parts of the world. So that’s a problem-solving methodology. It’s nothing different. It just uses technology and feedback loops in a fast way. The other one is exploratory data analysis. When you’re dealing with a large-scale problem, and there’s so much data, I can get to the heuristics that Charles was talking about through very clever visualization of data.

You test with your data. You need to set up an environment to do so, but don’t get caught up in neural-network modeling immediately. You’re testing, you’re checking—“Is the data right? Is it sound? Does it make sense?”—before you launch too far.

Simon London: You do hear these ideas—that if you have a big enough data set and enough algorithms, they’re going to find things that you just wouldn’t have spotted, find solutions that maybe you wouldn’t have thought of. Does machine learning sort of revolutionize the problem-solving process? Or are these actually just other tools in the toolbox for structured problem solving?

Charles Conn: It can be revolutionary. There are some areas in which the pattern recognition of large data sets and good algorithms can help us see things that we otherwise couldn’t see. But I do think it’s terribly important we don’t think that this particular technique is a substitute for superb problem solving, starting with good problem definition. Many people use machine learning without understanding algorithms that themselves can have biases built into them. Just as 20 years ago, when we were doing statistical analysis, we knew that we needed good model definition, we still need a good understanding of our algorithms and really good problem definition before we launch off into big data sets and unknown algorithms.

Simon London: Step six. You’ve done your analysis.

Charles Conn: I take six and seven together, and this is the place where young problem solvers often make a mistake. They’ve got their analysis, and they assume that’s the answer, and of course it isn’t the answer. The ability to synthesize the pieces that came out of the analysis and begin to weave those into a story that helps people answer the question “What should I do?” This is back to where we started. If we can’t synthesize, and we can’t tell a story, then our decision maker can’t find the answer to “What should I do?”

Simon London: But, again, these final steps are about motivating people to action, right?

Charles Conn: Yeah.

Simon London: I am slightly torn about the nomenclature of problem solving because it’s on paper, right? Until you motivate people to action, you actually haven’t solved anything.

Charles Conn: I love this question because I think decision-making theory, without a bias to action, is a waste of time. Everything in how I approach this is to help people take action that makes the world better.

Simon London: Hence, these are absolutely critical steps. If you don’t do this well, you’ve just got a bunch of analysis.

Charles Conn: We end up in exactly the same place where we started, which is people speaking across each other, past each other in the public square, rather than actually working together, shoulder to shoulder, to crack these important problems.

Simon London: In the real world, we have a lot of uncertainty—arguably, increasing uncertainty. How do good problem solvers deal with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: At every step of the process. In the problem definition, when you’re defining the context, you need to understand those sources of uncertainty and whether they’re important or not important. It becomes important in the definition of the tree.

You need to think carefully about the branches of the tree that are more certain and less certain as you define them. They don’t have equal weight just because they’ve got equal space on the page. Then, when you’re prioritizing, your prioritization approach may put more emphasis on things that have low probability but huge impact—or, vice versa, may put a lot of priority on things that are very likely and, hopefully, have a reasonable impact. You can introduce that along the way. When you come back to the synthesis, you just need to be nuanced about what you’re understanding, the likelihood.

Often, people lack humility in the way they make their recommendations: “This is the answer.” They’re very precise, and I think we would all be well-served to say, “This is a likely answer under the following sets of conditions” and then make the level of uncertainty clearer, if that is appropriate. It doesn’t mean you’re always in the gray zone; it doesn’t mean you don’t have a point of view. It just means that you can be explicit about the certainty of your answer when you make that recommendation.

Simon London: So it sounds like there is an underlying principle: “Acknowledge and embrace the uncertainty. Don’t pretend that it isn’t there. Be very clear about what the uncertainties are up front, and then build that into every step of the process.”

Hugo Sarrazin: Every step of the process.

Simon London: Yeah. We have just walked through a particular structured methodology for problem solving. But, of course, this is not the only structured methodology for problem solving. One that is also very well-known is design thinking, which comes at things very differently. So, Hugo, I know you have worked with a lot of designers. Just give us a very quick summary. Design thinking—what is it, and how does it relate?

Hugo Sarrazin: It starts with an incredible amount of empathy for the user and uses that to define the problem. It does pause and go out in the wild and spend an enormous amount of time seeing how people interact with objects, seeing the experience they’re getting, seeing the pain points or joy—and uses that to infer and define the problem.

Simon London: Problem definition, but out in the world.

Hugo Sarrazin: With an enormous amount of empathy. There’s a huge emphasis on empathy. Traditional, more classic problem solving is you define the problem based on an understanding of the situation. This one almost presupposes that we don’t know the problem until we go see it. The second thing is you need to come up with multiple scenarios or answers or ideas or concepts, and there’s a lot of divergent thinking initially. That’s slightly different, versus the prioritization, but not for long. Eventually, you need to kind of say, “OK, I’m going to converge again.” Then you go and you bring things back to the customer and get feedback and iterate. Then you rinse and repeat, rinse and repeat. There’s a lot of tactile building, along the way, of prototypes and things like that. It’s very iterative.

Simon London: So, Charles, are these complements or are these alternatives?

Charles Conn: I think they’re entirely complementary, and I think Hugo’s description is perfect. When we do problem definition well in classic problem solving, we are demonstrating the kind of empathy, at the very beginning of our problem, that design thinking asks us to approach. When we ideate—and that’s very similar to the disaggregation, prioritization, and work-planning steps—we do precisely the same thing, and often we use contrasting teams, so that we do have divergent thinking. The best teams allow divergent thinking to bump them off whatever their initial biases in problem solving are. For me, design thinking gives us a constant reminder of creativity, empathy, and the tactile nature of problem solving, but it’s absolutely complementary, not alternative.

Simon London: I think, in a world of cross-functional teams, an interesting question is do people with design-thinking backgrounds really work well together with classical problem solvers? How do you make that chemistry happen?

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah, it is not easy when people have spent an enormous amount of time seeped in design thinking or user-centric design, whichever word you want to use. If the person who’s applying classic problem-solving methodology is very rigid and mechanical in the way they’re doing it, there could be an enormous amount of tension. If there’s not clarity in the role and not clarity in the process, I think having the two together can be, sometimes, problematic.

The second thing that happens often is that the artifacts the two methodologies try to gravitate toward can be different. Classic problem solving often gravitates toward a model; design thinking migrates toward a prototype. Rather than writing a big deck with all my supporting evidence, they’ll bring an example, a thing, and that feels different. Then you spend your time differently to achieve those two end products, so that’s another source of friction.

Now, I still think it can be an incredibly powerful thing to have the two—if there are the right people with the right mind-set, if there is a team that is explicit about the roles, if we’re clear about the kind of outcomes we are attempting to bring forward. There’s an enormous amount of collaborativeness and respect.

Simon London: But they have to respect each other’s methodology and be prepared to flex, maybe, a little bit, in how this process is going to work.

Hugo Sarrazin: Absolutely.

Simon London: The other area where, it strikes me, there could be a little bit of a different sort of friction is this whole concept of the day-one answer, which is what we were just talking about in classical problem solving. Now, you know that this is probably not going to be your final answer, but that’s how you begin to structure the problem. Whereas I would imagine your design thinkers—no, they’re going off to do their ethnographic research and get out into the field, potentially for a long time, before they come back with at least an initial hypothesis.

Want better strategies? Become a bulletproof problem solver

Hugo Sarrazin: That is a great callout, and that’s another difference. Designers typically will like to soak into the situation and avoid converging too quickly. There’s optionality and exploring different options. There’s a strong belief that keeps the solution space wide enough that you can come up with more radical ideas. If there’s a large design team or many designers on the team, and you come on Friday and say, “What’s our week-one answer?” they’re going to struggle. They’re not going to be comfortable, naturally, to give that answer. It doesn’t mean they don’t have an answer; it’s just not where they are in their thinking process.

Simon London: I think we are, sadly, out of time for today. But Charles and Hugo, thank you so much.

Charles Conn: It was a pleasure to be here, Simon.

Hugo Sarrazin: It was a pleasure. Thank you.

Simon London: And thanks, as always, to you, our listeners, for tuning into this episode of the McKinsey Podcast . If you want to learn more about problem solving, you can find the book, Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything , online or order it through your local bookstore. To learn more about McKinsey, you can of course find us at McKinsey.com.

Charles Conn is CEO of Oxford Sciences Innovation and an alumnus of McKinsey’s Sydney office. Hugo Sarrazin is a senior partner in the Silicon Valley office, where Simon London, a member of McKinsey Publishing, is also based.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Strategy to beat the odds

Five routes to more innovative problem solving

Problem Solving Versus Modeling

- First Online: 30 November 2009

Cite this chapter

- Judith Zawojewski 5

2936 Accesses

13 Citations

This chapter is the third in a series intended to prompt discussion and debate in the Problem Solving vs. Modeling Theme Group. The chapter addresses distinctions between problem solving and modeling as a means to understand and conduct research by considering three main issues: What constitutes a problem-solving vs. modeling task?; What constitutes problem-solving vs. modeling processes?; and What are some implications for research?

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

From Empirical Problem-Solving to Theoretical Problem-Finding Perspectives on the Cognitive Sciences

The Noble Art of Problem Solving

Problem Solving

Kelly, E. A., Lesh, R. A., and Baek, J. (Eds.) (2008). Handbook of design research methods in education: Innovations in science, technology, engineering and mathematics learning and teaching . London: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Lesh, R., Hoover, M., Hole, B., Kelly, E., and Post, T. (2000). Principles for developing thought-revealing activities for students and teachers. In A. Kelly, and R. Lesh (Eds.), Handbook of Research Design in Mathematics and Science Education. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Lesh, R., and Kelly, E. (2000). Multi-tiered teaching experiments. In E. Kelly, and R. Lesh (Eds.), Handbook of Research Design in Mathematics and Science Education. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Lesh, R., and Zawojewski, J. S. (2007). Problem solving and modeling. In F. Lester (Ed.), Second Handbook of Research on Mathematics Teaching and Learning (pp. 763–804). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Newell, A., and Simon, H. A. (1972). Human Problem Solving . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (1992). Learning to think mathematically: Problem solving, metacognition, and sense making in mathematics. In D. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Mathematics Teaching and Learning (pp. 334–370) . New York: McMillan.

Silver, E. A. (Ed.). (1985). Teaching and Learning Mathematical Problem Solving: Multiple Research Perspectives . Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Download references

Acknowledgment

Thank you to Frank K. Lester for his valuable feedback and suggestions, which led to revisions in this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL, 60616, USA

Judith Zawojewski

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Judith Zawojewski .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Education, Indiana University, N. Rose Ave. 201, Bloomington, 47405-1006, USA

Richard Lesh

Graduate School of Education, University of Queensland, Brisbane, 4074, Australia

Peter L. Galbraith

Dept. Continuing Education, City University, Northampton Square, London, EC1V 0HB, United Kingdom

Christopher R. Haines

School of Education, University of Utah, Campus Center Drive 1705, Salt Lake City, 84112, USA

Andrew Hurford

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2010 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Zawojewski, J. (2010). Problem Solving Versus Modeling. In: Lesh, R., Galbraith, P., Haines, C., Hurford, A. (eds) Modeling Students' Mathematical Modeling Competencies. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0561-1_20

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0561-1_20

Published : 30 November 2009

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4419-0560-4

Online ISBN : 978-1-4419-0561-1

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

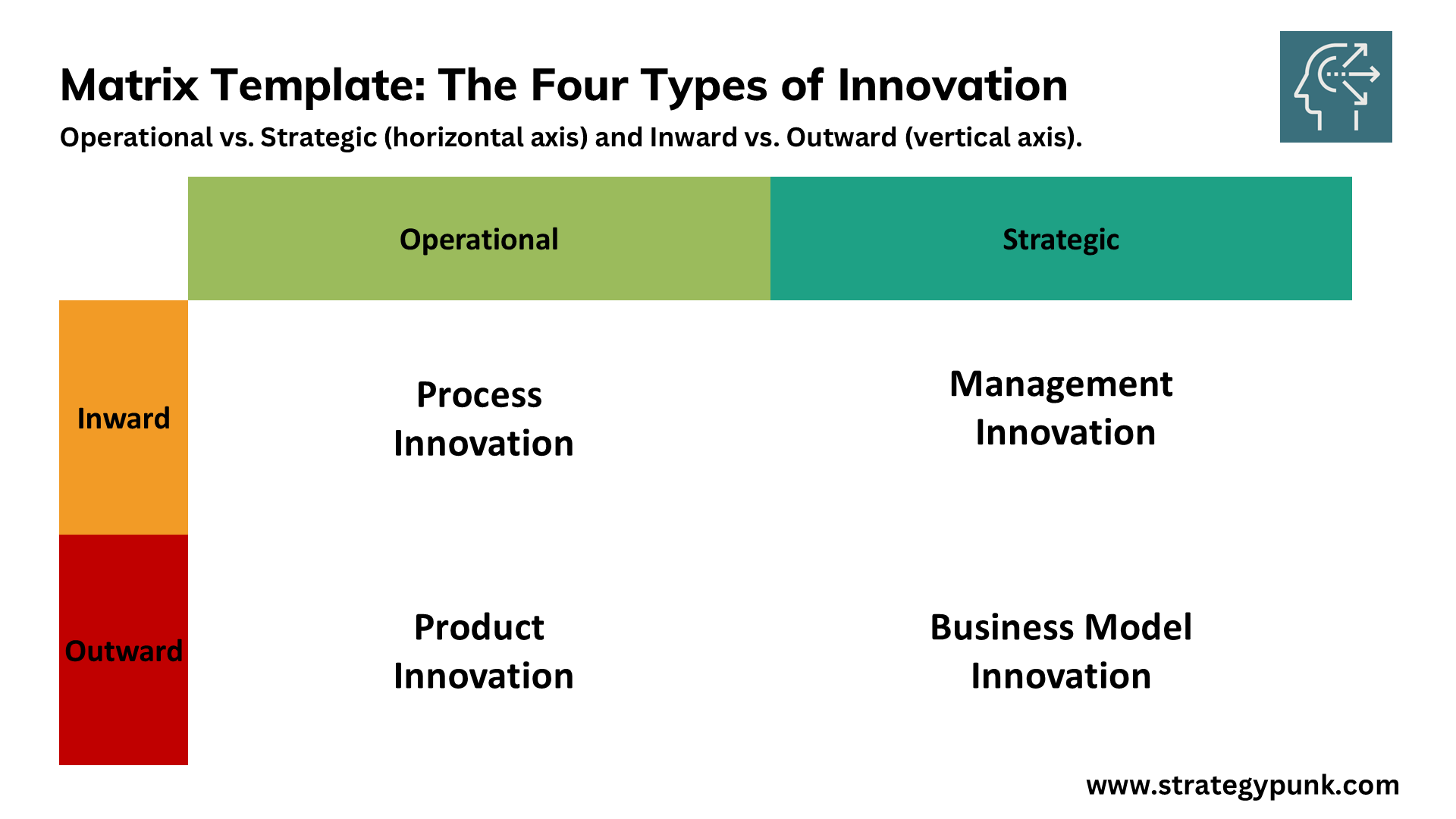

The 4 Types of Innovation and the Problems They Solve

by Greg Satell

Summary .

One of the best innovation stories I’ve ever heard came to me from a senior executive at a leading tech firm. Apparently, his company had won a million-dollar contract to design a sensor that could detect pollutants at very small concentrations underwater. It was an unusually complex problem, so the firm set up a team of crack microchip designers, and they started putting their heads together.

Partner Center

5 effective tools for problem solving - from logic trees to scenario planning

Share this article.

Solving problems may seem simple, but when we are faced with complex situations, it quickly becomes a challenge. Whether it's making decisions at work, in project teams or in private, it often requires more than a quick judgement. To reach the best solutions, we sometimes need tools that can help us see the big picture while managing the details.

Five Powerful Tools for Effective Problem Solving

Solving problems is a vital part of both work and everyday life. But some problems are too complex or uncertain to tackle all at once. In these situations, structured tools can help us better understand the issues, analyze alternatives, and make well-thought-out choices. Five useful tools for this are logic trees, decision trees, weighted factor analysis, premortem analysis, and scenario planning. These tools help organize complex issues and make it possible to break down, prioritize, and prepare for various outcomes.

In this article, we’ll explore how each tool works, when they’re best used, and provide concrete examples. Whether you’re making high-stakes strategic decisions at work or tackling challenges in your personal life, these tools can help you take your next steps with greater confidence.

Logic Trees: Break Down the Problem Step by Step

A logic tree is a tool that helps break down a complex problem into smaller, more manageable parts. By visualizing the issue in a logic tree, you can see the entire structure and identify the areas most relevant to finding a solution. This approach is especially helpful when a problem has several potential causes or paths forward. By mapping out the components in a tree, you can analyze each branch separately and focus on the areas that need extra attention.

Example: Imagine a company trying to understand why its sales are declining. Using a logic tree, they can break down the problem into different possible causes, such as customer satisfaction, marketing strategy, product quality, and pricing. Each part of the tree can then be analyzed to see where the issue might lie. Is it a drop in customer interest, or perhaps a shift in their marketing strategy that’s impacting sales?

Logic trees make it easier to see the big picture without missing important details. It’s a practical method for organizing thoughts and ensuring no part of the problem gets overlooked.

Decision Trees: Analyze Options and Risks in Uncertain Situations

Decision trees are valuable when you need to make choices involving multiple possible outcomes and risks. A decision tree is a graphical model where each branch represents an option and its potential consequences. By mapping out various paths, you can more easily assess which risks and opportunities are involved and choose the option that yields the best results.

Example: An investor considering buying a property can use a decision tree to assess different market scenarios. For the initial decision – to buy or not buy – the tree can show possible outcomes based on the market’s future. If the property market increases in value, the investment could be profitable, but if it declines, the outcome will be different. The decision tree helps the investor understand potential risks and make a more informed choice.

With a decision tree, you can quickly see which options are most advantageous and prepare for what might happen based on your decisions. This helps you act more strategically, especially in uncertain situations.

Weighted Factor Analysis: Compare Options Using Weighted Criteria

Weighted factor analysis is a method for comparing different options based on criteria that carry different levels of importance. By listing out weighted criteria, you can see which option best fits your priorities. This method is particularly useful for decisions with many factors and makes it simple to rank options based on your preferences.

Example: A family considering a move to a new city can use weighted factor analysis to compare different locations. They may prioritize factors such as schools, recreational activities, housing costs, and proximity to work. By assigning each factor a weight, the family can see which city best matches their needs and preferences.

Weighted factor analysis allows you to make decisions that are objective and based on what truly matters most to you, rather than just following a gut feeling. It provides a clear picture of which option is most advantageous.

Premortem Analysis: Anticipate Problems Before They Occur

Premortem analysis is a tool used to identify potential problems before they happen. Instead of waiting for issues to arise, you imagine that the project has already failed and analyze what might have gone wrong. By identifying potential obstacles in advance, you reduce the chances of those problems occurring.

Example: A project team working on a product launch can use a premortem before the launch date. They imagine that the launch didn’t go as planned and explore possible reasons – was the marketing insufficient, or did they overlook a key customer segment? By taking the time for a premortem, the team can find solutions in advance, making the launch more robust and thought-out.

Premortem analysis is especially useful for complex projects with many uncertainties. It helps teams think strategically and prepare for potential pitfalls.

Scenario Planning: Prepare for Different Future Situations

Scenario planning is a way to plan for various possible future outcomes. By creating different scenarios, you can prepare for a range of situations that may arise, especially when the future is uncertain. This tool is particularly useful for long-term strategies where both positive and negative changes can impact the outcome.

Example: A company planning its long-term strategy can use scenario planning to prepare for different market developments. They might consider what happens if new technologies change the industry or if political changes impact their operations. By developing scenarios, the company can craft strategies for each situation, giving them greater flexibility and security for the future.

Scenario planning helps you think broadly and be ready for multiple outcomes, allowing you to respond quickly and adapt to changes.

Summary: Strengthen Your Decision-Making with Structured Tools

Using these tools – logic trees, decision trees, weighted factor analysis, premortem analysis, and scenario planning – can enhance your problem-solving skills. They help you organize and prioritize your choices, making it easier to make thoughtful decisions in both professional and personal situations. When you use these tools, you’re better equipped to tackle challenges, manage uncertainty, and make decisions that lead you in the right direction.

Did you like this article? Here is more...

Team motivation and engagement: differences and strategies for leaders, decision-making model for continuous improvement, agile agile way of working agile working methods we explain.

Strategy development

Some key concepts in business planning.

Business Model Canvas

Sme performance management, managing director / ceo, board of directors.

- Find Flashcards

- Make Flashcards

- Why It Works

- Tutors & resellers

- Content partnerships

- Teachers & professors

- Employee training

- Get Started

Brainscape's Knowledge Genome TM

Entrance exams, professional certifications.

- Foreign Languages

- Medical & Nursing

Humanities & Social Studies

Mathematics, health & fitness, business & finance, technology & engineering, food & beverage, random knowledge, see full index.

leadership 2 > chapter 1 > Flashcards

chapter 1 Flashcards

What statement is true regarding decision making? A) It is an analysis of a situation B) It is closely related to evaluation C) It involves choosing between courses of action D) It is dependent upon finding the cause of a problem

Decision making is a complex cognitive process often defined as choosing a particular course of action. Problem solving is part of decision making and is a systematic process that focuses on analyzing a difficult situation. Critical thinking, sometimes referred to as reflective thinking, is related to evaluation and has a broader scope than decision making and problem solving.

Which of the following statements is true regarding decision making?

A) Scientific methods provide identical decisions by different individuals for the same problems

B) Decisions are greatly influenced by each persons value system C) Personal beliefs can be adjusted for when the scientific approach to problem solving is used

D) Past experience has little to do with the quality of the decision

Ans: B Feedback: Values, life experience, individual preference, and individual ways of thinking will influence a persons decision making. No matter how objective the criteria will be, value judgments will always play a part in a persons decision making, either consciously or subconsciously.

What is a weakness of the traditional problem-solving model? A) Its need for implementation time B) Its lack of a step requiring evaluation of results C) Its failure to gather sufficient data D) Its failure to evaluate alternatives

Ans: A Feedback: The traditional problem-solving model is less effective when time constraints are a consideration. Decision making can occur without the full analysis required in problem solving. Because problem solving attempts to identify the root problem in situations, much time and energy are spent on identifying the real problem.

What influences the quality of a decision most often? A) The decision makers immediate superior B) The type of decision that needs to be made C) Questions asked and alternatives generated

D) The time of day the decision is made

Ans: C Feedback: The greater the number of alternatives that can be generated by the decision maker, the better the final decision will be. The alternatives generated and the final choices are limited by each persons value system.

What does knowledge about good decision making lead one to believe? A) Good decision makers are usually right-brain, intuitive thinkers B) Effective decision makers are sensitive to the situation and to others C) Good decisions are usually made by left-brain, logical thinkers D) Good decision making requires analytical rather than creative processes

Ans: B Feedback: Good decision makers seem to have antennae that make them particularly sensitive to other people and situations. Left-brain thinkers are typically better at processing language, logic, numbers, and sequential ordering, whereas right-brain thinkers excel at nonverbal ideation and holistic synthesizing.

What is the best definition of decision making? A) The planning process of management B) The evaluation phase of the executive role C) One step in the problem-solving process D) Required to justify the need for scarce items

Ans: C Feedback: Decision making is a complex, cognitive process often defined as choosing a particular course of action. Decision making, one step in the problem-solving process, is an important task that relies heavily on critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills.

If decision making is triggered by a problem with what does it end?

A) An alternative problem B) A chosen course of action C) An action that guarantees success D) A restatement of the solution

Ans: B Feedback: A decision is made when a course of action has been chosen. Problem solving is part of decision making and is a systematic process that focuses on analyzing a difficult situation. Problem solving always includes a decision-making step.

Why do our values often cause personal conflict in decision making?

A) Some values are not realistic or healthy B) Not all values are of equal worth C) Our values remain unchanged over time D) Our values often collide with one another

Ans: D Feedback: Values, life experience, individual preference, and individual ways of thinking will influence a persons decision making. No matter how objective the criteria will be, value judgments will always play a part in a persons decision making, either consciously or subconsciously.

Which statement is true concerning critical thinking?

A) It is a simple approach to decision making B) It is narrower in scope than decision making C) It requires reasoning and creative analysis D) It is a synonym for the problem-solving process

Ans: C Feedback: Critical thinking has a broader scope than decision making and problem solving. It is sometimes referred to as reflective thinking. Critical thinking also involves reflecting upon the meaning of statements, examining the offered evidence and reasoning, and forming judgments about facts.

How do administrative man managers make the majority of their decisions?

A) After gathering all the facts B) In a manner good enough to solve the problem C) In a rational, logical manner D) After generating all the alternatives possible

Ans: B Feedback: Many managers make decisions that are just igood enoughi because of lack of time, energy, or creativity to generate a number of alternatives. This is also called isatisficing.i Most people make decisions too quickly and fail to systematically examine a problem or its alternatives for solution.

What needs to be considered in evaluating the quality of ones decisions? A) Is evaluation necessary when using a good decision-making model? B) Can evaluation be eliminated if the problem is resolved? C) Will the effectiveness of the decision maker be supported? D) Will the evaluation be helpful in increasing ones decision-making skills?

Ans: D Feedback: The evaluation phase is necessary to find out more about ones ability as a decision maker and to find out where the decision making was faulty.

Which statement concerning the role of the powerful in organizational decision making is true?

A) They exert little influence on decisions that are made B) They make decisions made that are in congruence with their own values C) They allow others to make the decisions however they wish D) They make all the important decisions with consideration to others

Ans: B Feedback: Not only does the preference of the powerful influence decisions of others in the organization, but the powerful are also able to inhibit the preferences of the less powerful. Powerful people in organizations are more likely to have decisions made that are congruent with their own preferences and values.

What effect of organizational power on decision making is often reflected in the tendency of staff?

A) Making decisions independent of organizational values B) Not trusting others to decide C) Desiring personal power D) Having private beliefs that are separate from corporate ones

Ans: D Feedback: The ability of the powerful to influence individual decision making in an organization often requires adopting a private personality and an organizational personality.

what Affirming the consequences Arguing from analogy Deductive reasoning Overgeneralizing A) Examine alternatives visually and compare each against the same criteria B) Quantify information C) Plot a decision over time D) Predict when events must take place to complete a project on time

Ans: A Feedback: A decision grid allows one to visually examine the alternatives and compare each against the same criteria. Although any criteria may be selected, the same criteria are used to analyze each alternative.

does a decision grid allow the decision maker to do?

ns: A Feedback: Management decision-making aides are subject to human error. Some of these aides encourage analytical thinking, others are designed to increase intuitive reasoning, and a few encourage the use of both hemispheres of the brain. Despite the helpfulness of these tools, there is a strong tendency for managers to favor first impressions when making a decision, and a second tendency, called confirmation biases, often follows

Which statement is true regarding an economic man style manager?

A) Lacks complete knowledge and generates few alternatives B) Makes decisions that may not be ideal but result in solutions that have an adequate outcome

C) Makes most management decisions using the administrative man model of decision making

D) These managers gather as much information as possible and generate many alternatives

Economic managers gather as much information as possible and generate many alternatives. Most management decisions are made by using the administrative man model of decision making. The administrative man never has complete knowledge and generates fewer alternatives

what is heuristics? A) Discrete, unconscious process to allow individuals to solve problems quickly B) Set of rules to encourage learners to discover solutions for themselves C) Formal process and structure in the decision-making process D) Trial-and-error method or rules-of-thumb approach

Ans: A Feedback: Most individuals rely on discrete, often unconscious processes known as heuristics, which allows them to solve problems more quickly and to build upon experiences they have gained in their lives. Thus, heuristics use trial-and-error methods or a rules-of- thumb approach, rather than set rules, and in doing so, encourages learners to discover solutions for themselves.

Ans: C Feedback: Analytical, linear, left-brain thinkers process information differently from creative, intuitive, right-brain thinkers. Left-brain thinkers are typically better at processing language, logic, numbers, and sequential ordering, whereas right-brain thinkers excel at nonverbal ideation and holistic synthesizing.

Individuals with lower-left-brain dominance are highly organized and detail oriented and individuals with upper-left-brain dominance truly are analytical thinkers who like working with factual data and numbers. These individuals deal with problems in a logical and rational way. Individuals with upper-right-brain dominance are big picture thinkers who look for hidden possibilities and are futuristic in their thinking. Individuals with lower-right-brain dominance experience facts and problem solve in a more emotional way than the other three types.

Which problem-solving learning strategy provides the learner with the most realistic, risk-free learning environment?

A) Case studies B) Simulation C) Problem-based learning (PBL) D) Grand rounds

Ans: B Feedback:

Simulation provides learners opportunities for problem solving that have little or no risk to patients or to organizational performance while providing models, either mechanical or live, to provide experiences for the learner. While the other options provide learning opportunities that include problem solving, simulation is the most realistic while also being low risk.

Which statement demonstrates a characteristic of a critical thinker? Select all that apply.

A) iSince that didnt work effectively, lets try something different.i B) iThe solution has to be something the patient is willing to do.i C) iIll talk to the patients primary care giver about the problem.i D) iMaybe there is no new solution to this particular problem.i

Ans: A, B, C Feedback: A critical thinker displays persistence, empathy, and assertiveness. The remaining options reflect limited thinking and an inability to think outside the box.

What is the value of using a structured approach to problem solving for the novice nurse?

A) Facilitates effective time management B) Supports the acquisition of clinical reasoning C) Supplements the orientation process D) Encourages professional autonomy

Ans: B Feedback: A structured approach to problem solving and decision making increases clinical reasoning and is the best way to learn how to make quality decisions because it eliminates trial and error and focuses the learning on a proven process. This is particularly helpful to the novice nurse with limited clinical experience and intuition. The other options are outcomes of the possession of critical thinking skills and clinical reasoning.

Which situation is characteristic of the weakness of the nursing process?

A) The frequent absence of well-written patience-focused objectives B) The confusion created by the existence of numerous nursing diagnoses C) The ever-increasing need for effective assessment skills required of the nurse D) The amount of nursing staff required to implement the patients plans of care

Ans: A Feedback: The weakness of the nursing process, like the traditional problem-solving model, is in not requiring clearly stated objectives. Goals should be clearly stated in the planning phase of the process, but this step is frequently omitted or obscured. While the remaining options relate to the nursing process, they are not directly a result of the process itself.

What is the advantage of using a payoff table when applicable? A) It assures the correct decision when dealing with financial situations B) It is very helpful when quantitative information about the topic is available C) It assists in the visualization of the available historic and current data D) It is easy to construct even for the novice decision maker

Ans: C Feedback: Payoff tables do not guarantee that a correct decision will be made, but they assist in visualizing data. While it does lend itself to the use of quantitative data that are not its strength, the table may not be difficult to construct that is not its strength since it is dependent on the inclusion of accurate data and effective evaluation of that data.

leadership 2 (5 decks)

- chapter 8 & 9

- Corporate Training

- Teachers & Schools

- Android App

- Help Center

- Law Education

- All Subjects A-Z

- All Certified Classes

- Earn Money!

Master the 7-Step Problem-Solving Process for Better Decision-Making

Discover the powerful 7-Step Problem-Solving Process to make better decisions and achieve better outcomes. Master the art of problem-solving in this comprehensive guide. Download the Free PowerPoint and PDF Template.

StrategyPunk

Introduction

Mastering the art of problem-solving is crucial for making better decisions. Whether you're a student, a business owner, or an employee, problem-solving skills can help you tackle complex issues and find practical solutions. The 7-Step Problem-Solving Process is a proven method that can help you approach problems systematically and efficiently.

The 7-Step Problem-Solving Process involves steps that guide you through the problem-solving process. The first step is to define the problem, followed by disaggregating the problem into smaller, more manageable parts. Next, you prioritize the features and create a work plan to address each. Then, you analyze each piece, synthesize the information, and communicate your findings to others.

By following this process, you can avoid jumping to conclusions, overlooking important details, or making hasty decisions. Instead, you can approach problems with a clear and structured mindset, which can help you make better decisions and achieve better outcomes.

In this article, we'll explore each step of the 7-Step Problem-Solving Process in detail so you can start mastering this valuable skill. At the end of the blog post, you can download the process's free PowerPoint and PDF templates .

Step 1: Define the Problem

The first step in the problem-solving process is to define the problem. This step is crucial because finding a solution is only accessible if the problem is clearly defined. The problem must be specific, measurable, and achievable.

One way to define the problem is to ask the right questions. Questions like "What is the problem?" and "What are the causes of the problem?" can help. Gathering data and information about the issue to assist in the definition process is also essential.

Another critical aspect of defining the problem is identifying the stakeholders. Who is affected by it? Who has a stake in finding a solution? Identifying the stakeholders can help ensure that the problem is defined in a way that considers the needs and concerns of all those affected.

Once the problem is defined, it is essential to communicate the definition to all stakeholders. This helps to ensure that everyone is on the same page and that there is a shared understanding of the problem.

Step 2: Disaggregate

After defining the problem, the next step in the 7-step problem-solving process is to disaggregate the problem into smaller, more manageable parts. Disaggregation helps break down the problem into smaller pieces that can be analyzed individually. This step is crucial in understanding the root cause of the problem and identifying the most effective solutions.

Disaggregation can be achieved by breaking down the problem into sub-problems, identifying the contributing factors, and analyzing the relationships between these factors. This step helps identify the most critical factors that must be addressed to solve the problem.

A tree or fishbone diagram is one effective way to disaggregate a problem. These diagrams help identify the different factors contributing to the problem and how they are related. Another way is to use a table to list the other factors contributing to the situation and their corresponding impact on the issue.

Disaggregation helps in breaking down complex problems into smaller, more manageable parts. It helps understand the relationships between different factors contributing to the problem and identify the most critical factors that must be addressed. By disaggregating the problem, decision-makers can focus on the most vital areas, leading to more effective solutions.

Step 3: Prioritize

After defining the problem and disaggregating it into smaller parts, the next step in the 7-step problem-solving process is prioritizing the issues that need addressing. Prioritizing helps to focus on the most pressing issues and allocate resources more effectively.

There are several ways to prioritize issues, including:

- Urgency: Prioritize issues based on their urgency. Problems that require immediate attention should be addressed first.

- Impact: Prioritize issues based on their impact on the organization or stakeholders. Problems with a high impact should be given priority.

- Resources: Prioritize issues based on the resources required to address them. Problems that require fewer resources should be dealt with first.

It is important to involve stakeholders in the prioritization process, considering their concerns and needs. This can be done through surveys, focus groups, or other forms of engagement.

Once the issues have been prioritized, developing a plan of action to address them is essential. This involves identifying the resources required, setting timelines, and assigning responsibilities.

Prioritizing issues is a critical step in problem-solving. By focusing on the most pressing problems, organizations can allocate resources more effectively and make better decisions.

Step 4: Workplan

After defining the problem, disaggregating, and prioritizing the issues, the next step in the 7-step problem-solving process is to develop a work plan. This step involves creating a roadmap that outlines the steps needed to solve the problem.

The work plan should include a list of tasks, deadlines, and responsibilities for each team member involved in the problem-solving process. Assigning tasks based on each team member's strengths and expertise ensures the work is completed efficiently and effectively.