Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 October 2020

Authentic self-expression on social media is associated with greater subjective well-being

- Erica R. Bailey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2924-2500 1 na1 ,

- Sandra C. Matz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0969-4403 1 na1 ,

- Wu Youyou 2 &

- Sheena S. Iyengar 1

Nature Communications volume 11 , Article number: 4889 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

125k Accesses

72 Citations

442 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

Social media users face a tension between presenting themselves in an idealized or authentic way. Here, we explore how prioritizing one over the other impacts users’ well-being. We estimate the degree of self-idealized vs. authentic self-expression as the proximity between a user’s self-reported personality and the automated personality judgements made on the basis Facebook Likes and status updates. Analyzing data of 10,560 Facebook users, we find that individuals who are more authentic in their self-expression also report greater Life Satisfaction. This effect appears consistent across different personality profiles, countering the proposition that individuals with socially desirable personalities benefit from authentic self-expression more than others. We extend this finding in a pre-registered, longitudinal experiment, demonstrating the causal relationship between authentic posting and positive affect and mood on a within-person level. Our findings suggest that the extent to which social media use is related to well-being depends on how individuals use it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Variation in social media sensitivity across people and contexts

Characteristics of online user-generated text predict the emotional intelligence of individuals

Like-minded sources on Facebook are prevalent but not polarizing

Introduction.

Social media can seem like an artificial world in which people’s lives consist entirely of exotic vacations, thriving friendships, and photogenic, healthy meals. In fact, there is an entire industry built around people’s desire to present idealistic self-representations on social media. Popular applications like FaceTune, for example, allow users to modify everything about themselves, from skin tone to the size of their physical features. In line with this “self-idealization perspective”, research has shown that self-expressions on social media platforms are often idealized, exaggerated, and unrealistic 1 . That is, social media users often act as virtual curators of their online selves 2 by staging or editing content they present to others 3 .

A contrasting body of research suggests that social media platforms constitute extensions of offline identities, with users presenting relatively authentic versions of themselves 4 . While users might engage in some degree of self-idealization, the social nature of the platforms is thought to provide a degree of accountability that prevents individuals from starkly misrepresenting their identities 5 . This is particularly true for platforms such as Facebook, where the majority of friends in a user’s network also have an offline connection 6 . In fact, modern social media sites like Facebook and Instagram are far more realistic than early social media websites such as Second Life, where users presented themselves as avatars that were often fully divorced from reality 7 . In line with this authentic self-expression perspective, research has shown that individuals on Facebook are more likely to express their actual rather than their idealized personalities 8 , 9 .

The desire to present the self in a way that is ideal and authentic is not mutually exclusive; on the contrary, an individual is likely to desire both simultaneously 10 . This occurs in part because self-idealization and authentic self-expression fulfill different psychological needs and are associated with different psychological costs. On the one hand, self-idealization has been called a “fundamental part of human nature” 11 because it allows individuals to cultivate a positive self-view and to create positive impressions of themselves in others 12 . In addition, authentic self-expression allows individuals to verify and affirm their sense of self 13 , 14 which can increase self-esteem 15 , and a sense of belonging 16 . On the other hand, self-idealizing behavior can be psychologically costly, as acting out of character is associated with feelings of internal conflict, psychological discomfort, and strong emotional reactions 17 , 18 ; individuals may also possess characteristics that are more or less socially desirable, bringing their desire to present themselves in an authentic way into conflict with their desire to present the best version of themselves.

Here, we explore the tension between self-idealization and authentic self-expression on social media, and test how prioritizing one over the other impacts users’ well-being. We focus our analysis on a core component of the self: personality 19 . Personality captures fundamental differences in the way that people think, feel and behave, reflecting the psychological characteristics that make individuals uniquely themselves 20 , 21 . Building on the Five Factor Model of personality 22 , we test the extent to which authentic self-expression of personality characteristics are related to Life Satisfaction, hypothesizing that greater authentic self-expression will be positively correlated with Life Satisfaction. In exploratory analyses, we also consider whether this relationship is moderated by the personality characteristics of the individual. That is, not all individuals might benefit from authentic self-expression equally. Given that some personality traits are more socially desirable than others 23 , individuals who possess more desirable personality traits are likely to experience a reduced tension between self-idealization and authentic self-expression. Consequently, individuals with more socially desirable profiles might disproportionality benefit from authentic self-expression because the motivational pulls of self-idealization and authentic self-expression point in the same—rather than the opposite—direction.

Previous literature on authentic self-expression has predominantly relied on self-reported perceptions of authenticity as (i) a state of feeling authentic 24 , or (ii) a judgement about the honesty or consistency of one’s self 25 . However, such self-reported measures have been shown to be biased by valence states, and social desirability 26 , 27 . To overcome these limitations, in Study 1 we introduce a measure of Quantified Authenticity. If authenticity is most simply defined as the unobstructed expression of one’s self 28 , then authenticity can be estimated as the proximity of an individual’s self-view and their observable self-expression. We calculate Quantified Authenticity by comparing self-reported personality to personality judgements made by computers on the basis of observable behaviors on Facebook (i.e., Likes and status updates).

By observing self-presentation on social media and comparing it to the individual’s self-view, we are able to quantify the extent to which an individual deviates from their authentic self. That is, we locate each individual on a continuum that ranges from low authenticity (i.e., large discrepancy between the self-view and observable self-expression) to high authenticity (i.e., perfect alignment between the self-view and observable self-expression). Importantly, our approach rests on the assumption that any deviation from the self-view on social media constitutes an attempt to present oneself in a more positive light, and therefore a form of self-idealization. While a deviation could theoretically indicate both self-idealization and self-deprecation, it is unlikely that users will deviate from their true selves in a way that makes them look worse in the eyes of others. A strength of our measures is that we do not postulate that self-idealization takes a particular form of deviation from the self or is associated with striving for a particular profile. Although research suggests that there are certain personality traits that are more desirable on average 29 , 30 , the extent to which a person sees scoring high or low on a given trait is likely somewhat idiosyncratic and depends—at least in part—on other people in their social network. For example, behaving in a more extraverted way might be self-enhancing for most people; however, there might be individuals for whom behaving in a more introverted way might be more desirable (e.g. because the norm of their social network is more introverted). Hence, our conceptualization of Quantified Authenticity allows for deviations in different directions (see Supplementary Information for more detail).

Quantified Authenticity and subjective well-being

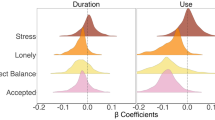

In Study 1, we analyzed the data of 10,560 Facebook users who had completed a personality assessment and reported on their Life Satisfaction through the myPersonality application 31 , 32 . To estimate the extent to which their Facebook profiles represent authentic expressions of their personality, we compared their self-ratings to two observational sources: predictions of personality from Facebook Likes ( N = 9237) 33 and predictions of personality from Facebook status updates ( N = 3215) 34 . These are based on recent advances in the automatic assessment of psychological traits from the digital traces they leave on Facebook 35 . For each of the observable sources, we calculated Quantified Authenticity as the inverse Euclidean distance between all five self-rated and observable personality traits. Our measure of Quantified Authenticity exhibits a desirable level of variance, ranging all the way from highly authentic self-expression to considerable levels of self-idealization (see ridgeline plot of Quantified Authenticity calculated for self-language and Self-Likes in Supplementary Fig. 3 , see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for zero-order correlations among variables).

To test the extent to which authentic self-expression is related to Life Satisfaction, we ran linear regression analyses predicting Life Satisfaction from the two measures of Quantified Authenticity (Likes, status updates). The results support the hypothesis that higher levels of authenticity (i.e. lower distance scores) are positively correlated with Life Satisfaction (Table 1 , Model 1 without controls). These effects remained statistically significant when controlling for self-reported personality traits. Additionally, we included a control variable for the overall extremeness of an individual’s personality profile (deviation from the population mean across all five traits), as people with more extreme personality profiles might find it more difficult to blend into society and therefore experience lower levels of well-being 36 (see Table 1 , Model 2 with controls; the results are largely robust when controlling for gender and age, see Supplementary Table 3 ; see Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 for interactions between individual self-reported and predicted personality traits).

To further explore the mechanisms of Quantified Authenticity, we conducted analyses that distinguished between normative self-enhancement (i.e., rating oneself as more Extraverted, Agreeable, Conscientiousness, Emotionally Stable, and Open-minded than is indicated by one’s Facebook behavior) from self-deprecation (i.e., rating oneself lower on all of these traits). While normative self-enhancement has a negative effect on well-being, normative self-deprecation has no effect. These findings suggest that self-enhancement specifically, rather than overall self-discrepancy/lack of authenticity, is detrimental to subjective well-being (see Supplementary Fig. 4 ).

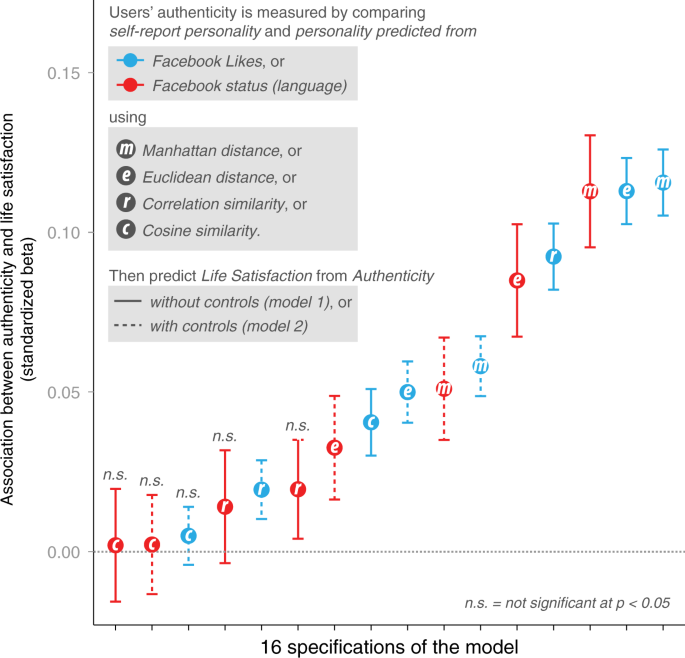

To test the robustness of our effects, we regressed Life Satisfaction on three additional measures of Quantified Authenticity (i.e., calculated using Manhattan Distance, Cosine Similarity, and Correlational Similarity; see SI for details on these measures). In both comparison sets (likes and status updates), we found significant and positive correlations between the various ways of estimating Quantified Authenticity (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 ). The standardized beta-coefficients across all four metrics of Quantified Authenticity and observable sources are displayed in Fig. 1 . Despite variance in effect sizes across measures and model specifications, the majority of estimates are statistically significant and positive (11 out of 16). Importantly, no coefficients were observed in the opposite direction. These results suggest that those who are more authentic in their self-expression on Facebook (i.e., those who present themselves in a way that is closer to their self-view) also report higher levels of Life Satisfaction.

Figure 1 presents standardized beta coefficients for Quantified Authenticity using ordinary least squares regressions in 16 individual regressions predicting Life Satisfaction. Quantified Authenticity is significantly associated with Life Satisfaction in 11 out of the 16 models. Quantified Authenticity is measured as the consistency between self-reported personality and two other sources of personality data: language and Likes, respectively, (indicated in red and blue color). Quantified Authenticity is defined using four distance metrics, respectively: Manhattan, Euclidean, correlation, and cosine similarity (indicated with a letter in the dots). Models with and without control variables are indicated with dashed and solid line, respectively.

In exploratory analyses, we considered whether authenticity might benefit individuals of different personalities differentially. In order to examine this, we regressed Life Satisfaction on the interactions between Quantified Authenticity and each of the five personality traits (e.g., Quantified Authenticity × Extraversion). The results of these interaction analyses did not provide reliable evidence for the proposition that individuals with socially desirable profiles (i.e., high openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and low neuroticism) benefit from authentic self-expression more than individuals with less socially desirable profiles (see Table 1 , Model 3). While the interactions of the five personality traits with Quantified Authenticity reached significance for some traits and measures, the results were not consistent across both observable sources of self-expression (Likes-based and Language-based). Consequently, we did not find reliable evidence that having a socially desirable personality profile boosts the effect of authenticity on well-being. Instead, individuals reported increased Life Satisfaction when they presented authentic self-expression, regardless of their personality profile.

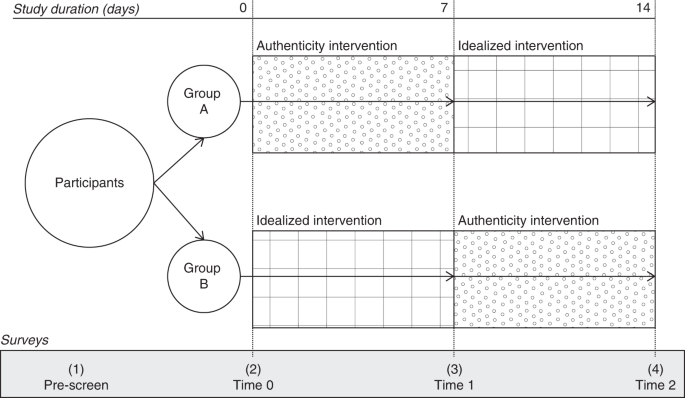

The findings of Study 1 provide evidence for the link between authenticity on social media and well-being in a setting of high external validity. However, given the correlational nature of the study, we cannot make any claims about the causality of the effects. While we hypothesize that expressing oneself authentically on social media results in higher levels of well-being, it is also plausible that individuals who experience higher levels of well-being are more likely to express themselves authentically on social media. To provide evidence for the directionality of authenticity on well-being, we conducted a pre-registered, longitudinal experiment in Study 2 (see Fig. 2 for an illustration of the experimental design).

Figure 2 presents the longitudinal experimental study design for Study 2 with key timepoints, interventions, and surveys.

Experimental manipulation of authentic self-expression on well-being

We recruited 90 students and social media users at a Northeastern University to participate in a 2-week study ( M age = 22.98, SD age = 4.17, 72.22% female). The sample size deviates from our pre-registered sample size of 200. The reason for this is that the behavioral research lab of the university was shut down after the first wave of data collection due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

All participants completed two intervention stages during which they were asked to post on their social media profiles in a way that was: (1) authentic for 7 days and (2) self-idealized for 7 days. The order in which participants completed the two interventions was randomly assigned. This experimental set-up allowed us to study the effects of authentic versus idealized self-expression on social media in between-person (week 1) and within-person analyses (comparison between week 1 and week 2). All analyses were pre-registered prior to data collection 37 . Given the reduced sample size, the effects reported in this paper are all as expected in effect size, but only partially reached significance at the conventional alpha = 0.05 level. Consequently, we also consider effects that reach significance at alpha = 0.10 as marginally significant.

All participants completed a personality pre-screen (IPIP) 38 prior to beginning the study, and received personalized feedback report at the beginning of the treatment period (t0). Both the authentic and self-idealized interventions (see Methods for details) asked participants to reflect on that feedback report and identify specific ways in which they could alter their self-expression on social media to align their posts more closely with their actual personality profile (authentic intervention) or to align their posts more closely with how they wanted to be seen by others (see Supplementary Information for treatment text and examples of responses). The operationalization of the treatment follows our conceptualization of Quantified Authenticity in Study 1 in that it does not prescribe the direction of personality change (e.g. towards higher levels of extraversion). Instead, this design leaves it up to participants what posting in a more desirable way means in relation to their current profile.

Participants self-reported their subjective well-being as Life Satisfaction 39 , a single-item mood measure, and positive and negative affect 40 a week after the first intervention (t1), and a week after the second intervention (t2). This design allowed us to examine the causal nature of posting for a week in which participants posted authentically (“authentic, real, or true”), compared to a week in which they posted in a self-idealized way (“ideal, popular or pleasing to others”). Specifically, we hypothesized that individuals who post more authentically over the course of a week would self-report greater subjective well-being at the end of that week, both at the between and within-person level.

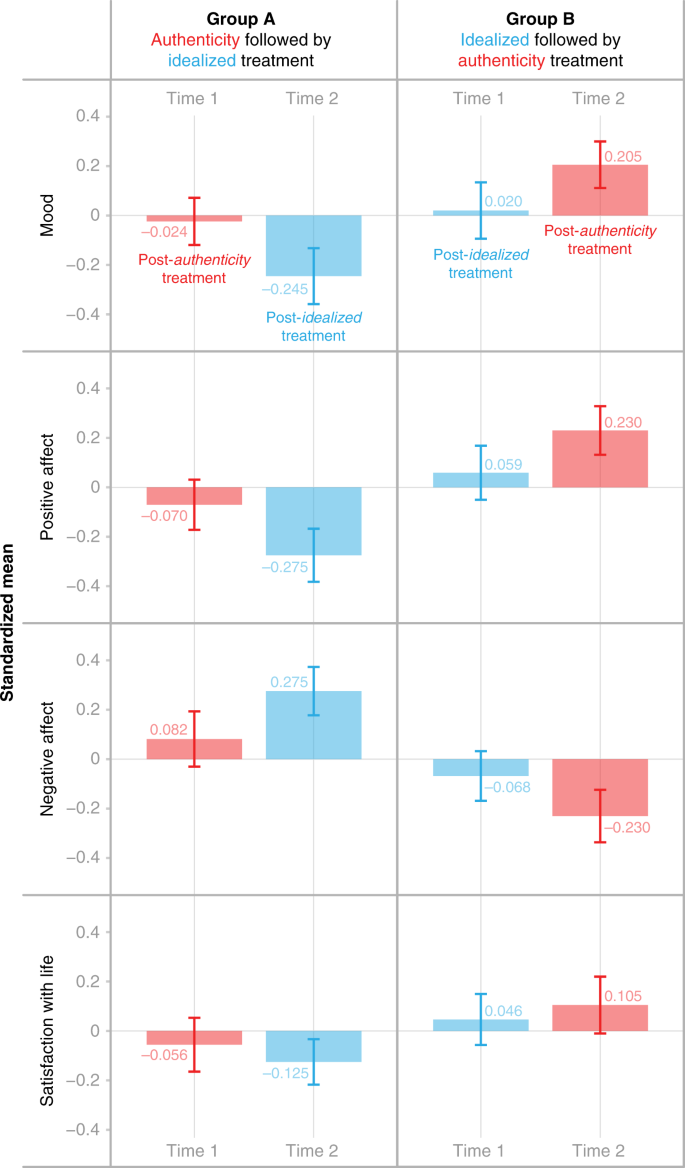

We examined the effect of authentic versus self-idealized expression at the between person level at t1 (see t1 in Fig. 3 ) using independent t -tests. Contrary to our expectations, we did not find any significant differences between the two conditions for any of the well-being indicators. This suggests that individuals in the authentic vs. self-idealized conditions did not differ from one another in their level of well-being after the first week of the study. However, when examining the effect within subjects using dependent t -tests we found that participants reported significantly higher levels of well-being after the week in which they posted authentically as compared to the week in which they posted in a self-idealized way. Specifically, the well-being scores in the authentic week were found to be significantly higher than in the self-idealized week for mood (mean difference = 0.19 [0.003, 0.374], t = 2.02, d = 0.43, p = 0.046) and for positive affect (mean difference = 0.17 [0.012, 0.318], t = 2.14, d = 0.45, p = 0.035), and marginally significant for negative affect (mean difference = −0.20 [−0.419, 0.016], t = −1.84, d = 0.39, p = 0.069). There was no significant effect on Life Satisfaction (mean difference = 0.09 [−0.096, 0.274], t = 0.96, d = 0.20, p = 0.342).

The bar chars illustrate the standardized mean of well-being indicators (mood, positive affect, negative affect, and Life Satisfaction) across two study time points by condition. The red bars indicate scores for the weeks in which participants were asked to post authentically, and the blue bars scores for the weeks in which they were asked to post in a self-idealized way. Error bars represent standard errors. The left-side panel presents Group A who received the authenticity treatment followed by the idealized treatment. The right-side panel presents Group B who received the idealized treatment followed by the authenticity treatment. This experiment was conducted once with independent samples in each group.

These findings are reflected in Fig. 3 which showcases the interactions between condition and time point. The graphs highlight that subjective well-being was higher in the weeks in which participants were asked to post authentically (red bars) compared to those in which they were asked to post in a self-idealized way (blue bars). While there was no difference in subjective well-being across conditions at t1, subjective well-being measures differed significantly between the authentic and self-idealized conditions at t2. We found no significant difference between conditions on Life Satisfaction (mean difference = 0.29 [−0.226, 0.798], t = 1.11, d = 0.23, p = 0.270), however, we found a significant difference between conditions such that the group which received the authenticity treatment had greater positive affect (mean difference = 0.45 [0.083, 0.825], t = 2.43, d = 0.51 , p = 0.017), lower negative affect (mean difference = −0.57 [−1.034, −0.113], t = −2.47, d = 0.52, p = 0.015), and higher overall mood (mean difference = 0.40 [0.028, 0.775], t = 2.14, d = 0.45 , p = 0.036).

The findings of the experiment provide support for the causal relationship between posting authentically, compared to posting in a self-idealized way, on the more immediate affective indicators of subjective-wellbeing, including mood and affect, but not on the more long-term, cognitive indicator of life satisfaction. This findings aligns with our pre-registration in that we had predicted mood and affect measures to be more sensitive to the treatment compared to Life Satisfaction, which is a broader global assessment one’s overall life 39 and less likely to change in the course of a week.

Additionally, the fact that we did not find significant effects in our between-subjects analysis in the first week of the study suggests that authentic self-expression might be difficult to manipulate in a one-off treatment as social media users are likely used to expressing themselves on social media both authentically and in a self-idealized way. Thus, when only one strategy is emphasized, participants might not shift their behavior. This is supported by the finding that participants did not differ significantly in their subjective experience of authenticity on social media at t1 (mean in authentic condition at t1 = 5.56, mean in self-idealized condition at t1 = 5.55, t = 0.05, d = 0.01, p = 0.958; Participants responded to a single item, which read “This past week, I was authentic on social media” on a 7-point scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree), indicating that the between-subjects manipulation was unsuccessful in getting people to shift their behaviors more toward self-idealized or authentic self-expression compared to their baseline. However, the contrast of the two strategies highlighted in the within-subjects part of the study seems to have successfully shifted participants’ behavior. When compared within person, students did indeed report higher levels of experienced authenticity in their posting during the week in which they were instructed to post authentically (mean difference = 0.30 [0.044, 0.556], t = 2.33, d = 0.49, p = 0.022).

We often hear the advice to just be ourselves. Indeed, psychological theories have suggested that behaving in a way that is consistent with the self-view is beneficial for individual well-being 41 . However, prior investigations of authenticity and well-being have relied solely on self-reported measures which can be confounded by valence and social desirability biases. We estimated authenticity as the proximity between the self-view and self-expression on social media—which we termed Quantified Authenticity—and found that authentic self-expression on social media was correlated with greater Life Satisfaction, an important component of overall well-being. This effect was robust across two comparison points, computer modeled personality based on Facebook Likes and status updates. Our findings suggest that if users engage in self-expression on social media, there may be psychological benefits associated with being authentic. We replicate this finding in a longitudinal experiment with university students; being prompted to post in an authentic way was associated with more positive mood and affect, and less negative mood within participants. Contrary to our second hypothesis, we did not find consistent support for interactions between personality traits and authenticity, such that individuals with more socially desirable traits would benefit more from behaving authentically. Instead, our findings suggest that all individuals regardless of personality traits could benefit from being authentic on social media.

Our findings contribute to the existing literature by speaking directly to conflicting findings on the effects of social media use on well-being. Some studies find that social media use increases self-esteem and positive self-view 42 , while others find that social media use is linked to lower well-being 43 . Still, others find that the effect of social media on well-being is small 44 or non-existent 45 . In an attempt to reconcile these mixed findings, researchers have suggested that the extent to which social media platforms related to lower or higher levels of well-being might depend not on whether people use them but on how they use them. For example, research has shown that active versus passive Facebook use has divergent effects on well-being. While passively using Facebook to consume the content share by others was negatively related to well-being, actively using Facebook to share content and communicate was not 46 . We add to this growing body of research by suggesting that effects of social media use on well-being may also be explained by individual differences in self-expression on social media.

Our study has a number of limitations that should be addressed by future research. First, our analyses focused exclusively on the effects of authentic social media use on well-being, and cannot speak to the question of whether an authentic social media use is better or worse than not using social media at all. That is, even though using social media authentically is better than using it in a more self-idealizing way, the overall effect of social media use on well-being might still be a negative. Future research could address this question by directly comparing no social media use to authentic social media use in both correlational and experimental settings.

Second, our findings do not provide any insights into why individuals might behave more or less authentically. For example, a deviation from the self-view might be explained by a lack of self-awareness, or an intentional misrepresentation of the self. It is possible that depending on whether deviation is driven by intent or not, authenticity might be more or less strongly related to well-being. That is, the psychological costs of deviating from one’s self-view might be stronger when they are intentional such that the individual is fully aware of the fact that they are behaving in a self-idealizing way. Future research should explore this factor empirically.

Finally, the effects of authentic self-presentation on social media on well-being are robust but small (max(β) = 0.11) when compared to compared to other important predictors of well-being such as income, physical health, and marriage 47 , 48 , 49 . However, we argue that the effects described here are meaningful when trying to understand a complex and multifaceted construct such as Life Satisfaction. First, Study 1 captures authenticity using observations of actual behavior rather than self-reports. Given that such behavioral data captured in the wild do not suffer from the same response biases as self-reports which can inflate relationships between variables (e.g. common method bias 50 ), and are often noisier than self-reports, their effect sizes cannot be directly compared 51 . In fact, the effect sizes obtained in Study 2 which was conducted in a much more controlled, experimental setting shows that the effect of authenticity on subjective well-being is substantially larger when measured with more traditional methods (max(d) = 0.45). In addition, while other factors such as employment and health are stronger predictors of well-being, they can be outside of the immediate control of the individual. In contrast, posting on social media in a way that is more aligned with an individual’s personality is both up to the individual and relatively easy to change.

Social media is a pervasive part of modern social life 52 . Nearly 80% of Americans use some form of social media, and three quarters of users check these accounts on a daily basis 53 . Many have speculated that the artificiality of these platforms and their trend towards self-idealization can be detrimental for individual well-being. Our results suggest that whether or not engaging with social media helps or hurts an individual’s well-being might be partly driven by how they use those platforms to express themselves. While it may be tempting to craft a self-enhanced Facebook presence, authentic self-expression on social media can be psychologically beneficial.

Study 1. Participants and procedure

Data were collected through the MyPersonality project, an application available on Facebook between 2007 and 2012 31 . Users of the app completed validated psychometric tests including a measure of the Big Five personality traits 22 , 54 , and received immediate feedback on their responses. A subsample of myPersonality users also agreed to donate their Facebook profile information—including their public profiles, their Facebook likes, their status updates, etc.—for research purposes. In addition, users could invite their Facebook friends to complete the personality questionnaire on their behalf, judging not their own personality but that of their friend.

To calculate authenticity, we developed a measure we refer to as Quantified Authenticity (QA). To compute this measure, we compared a person’s self-reported personality to two external criteria: (1) their personality as predicted from Facebook Likes, and (2) their personality as predicted from the language used in their status updates (see “Measures” section below for more information). The number of participants varied between the two samples based on exclusionary criteria. To be included in the Language-based model, individuals had to have posted at least 500 words of Facebook status updates ( N = 3215). In the Likes-based model, only participants with 20 or more Likes were included ( N = 9237).

Big Five personality

Participants’ personality was measured using the well-established Five Factor model of personality, also known as Big Five traits 54 , 55 . The Five Factor model posits five relatively stable, continuous personality traits: Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. The Big Five personality traits have been found to be stable across cultures, instruments, and observers 56 . Additionally, years of research have linked them to a broad variety of behaviors, preferences and other consequential outcomes, including well-being 57 and behavior on Facebook 58 .

Self-reported personality

Participants’ views of their own personalities are based on the well-established International Personality Item Pool or IPIP 38 . Participants included in the analyses responded to 20–100 questions using a 5 point Likert-scale where 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Computer-based predictions of personality from likes and status updates

Recent methodological advances in machine learning have provided researchers with the ability to predict the personality of individuals from their social media profiles 33 , 34 , 35 . Here, we used personality prediction of personality from Facebook Likes and the language used in status updates. For Facebook Likes ( N = 9327), we obtained the personality predictions made by Youyou and colleagues 33 , who used a 10-fold cross-validated LASSO regression to predict Big Five personality traits out of sample. On average, the predictions captured personality with an accuracy of r = 0.56 (correlation between predicted and self-reported scores). For status updates ( N = 3215), we obtained the predictions made by Park et al. 34 , who used cross-validated Ridge regression to infer personality from language features, such as individual words, combinations of words (n-grams), and topics. On average, the predictions captured personality with an accuracy of r = 0.41 (correlation between predicted and self-reported scores).

Personality extremeness

We calculated extremeness of participants’ personality profiles as a control variable for our analyses by summing the absolute z -scores on all five traits. We include extremeness because extreme individual scores tend to produce larger absolute difference scores. Additionally, previous work has found that people with more extreme personality profiles might find it more difficult to blend into society and therefore experience lower levels of well-being 36 .

Self-ratings of well-being

Individuals reported their Life Satisfaction—a key component of subjective well-being—on a five-item scale 39 . The SWLS has been shown to be a meaningful psychological construct, correlated with a number of important life outcomes such as marital status and health 59 .

Quantified Authenticity

Quantified Authenticity was calculated in three steps. First, we z -standardized the personality scores on each of the three measures (self, Likes, language) to obtain a person’s relative standing on the five personality traits in comparison to the reference group. Second, we computed the distance between self-reported personality and each of the externally inferred personality profiles using Euclidean distance, a widely established distance measure, which has been used in previous psychological research 36 . To make our measure more intuitively interpretable, we finally subtracted the distance measure from zero to obtain a measure of Quantified Authenticity for which higher scores indicate higher levels of authenticity. See Eq. ( 1 ) below.

For individual i , x i is the Cartesian coordinate of the self-view in a 5 -dimensional personality space. For individual i, y i is the Cartesian coordinate of the language-, or likes-based personality. Our measure of Quantified Authenticity exhibited desirable level of variance, ranging all the way from highly authentic self-expression to considerable levels of self-idealization (see ridgeline plot of standardized Quantified Authenticity calculated based on Language and Likes in Supplementary Fig. 3 ). Additional information on the calculation of the three other metrics of Quantified Authenticity (i.e., Manhattan distance, correlational similarity, and cosine similarity) can be found in the SI.

Study 2. Participants and procedure

All study procedures were approved by the Columbia University Human Research Protection Office and informed consent was received from all study participants. Prior to completing the study, participants completed a pre-screening survey. This included a number of questions related to their social media activity and the BFI-2S as a measure of their Big Five personality traits 60 . Participants who qualified for the study were randomly assigned to one of two groups depicted as “Group A” and “Group B” in Fig. 3 ). Both groups received both interventions (authentic and self-idealized), however they received the treatments in a different order.

The study took place over the course of 2 weeks. On the first day of the study, participants received an email, which included the results of their personality test taken in the pre-screen. They then self-reported their baseline subjective well-being (t0). At the end of the survey, half of the students were asked to use the personality feedback to list three ways in which they could express themselves more authentically over the next week on social media. The second group was asked to list with three ways to express themselves in a more self-idealized way.

At the end of the first week, participants received an email with the second survey link. They completed the same subjective well-being measures (t1; Day 0–7), and were shown their personality feedback again as a reminder. The students who were previously assigned to the authentic condition were now asked to list three ways to express themselves in a more self-idealized way (based on their personality profile), and vice versa (reversing the intervention assignments). At the end of the second week, participants received an email with the final survey link. They completed the same subjective well-being measures (t2; Day 7–14).

Subjective well-being

Individuals reported their Life Satisfaction on the same five-item scale as Study 1 39 . In addition, participants responded to positive and negative affect 40 and a single-item general mood measure.

Preregistration note

We had pre-registered the use of the Positive and Negative Affect Scale 61 . However, due to an oversight of the research team, we accidentally collected data using the Brief Mood Inventory Scale 40 . In the SI, we replicate the results using a subset of items, which overlap between the BMIS and the PANAS-X. Given that the two scales are highly correlated, share the same format, and even share some of the same descriptors, we do not expect that the results would have been different when using the PANAS scale.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data for Study 1 are available upon request to the authors. Data for Study 2 relevant to the analyses described are available on our OSF page ( https://osf.io/fxav6/ ). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code to reproduce the analyses for Study 1 and Study 2 described herein is available on OSF ( https://osf.io/fxav6/ ).

Manago, A. M., Graham, M. B., Greenfield, P. M. & Salimkhan, G. Self-presentation and gender on MySpace. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 29 , 446–458 (2008).

Google Scholar

Hogan, B. The presentation of self in the age of social media: distinguishing performances and exhibitions online. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 30 , 377–386 (2010).

Chua, T. H. H. & Chang, L. Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 55 , 190–197 (2016).

Ellison, N., Steinfield, C. & Lampe, C. Spatially bounded online social networks and social capital. Int. Commun. Assoc. 36 , 1–37 (2006).

Pempek, T. A., Yermolayeva, Y. A. & Calvert, S. L. College students’ social networking experiences on Facebook. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol . 30 , 227–238 (2009).

Ross, C. et al. Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 25 , 578–586 (2009).

Boellstorff, T. Coming of age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human . (Princeton University Press, 2015).

Waggoner, A. S., Smith, E. R. & Collins, E. C. Person perception by active versus passive perceivers. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 45 , 1028–1031 (2009).

Back, M D. et al. Facebook profiles reflect actual personality, not self-idealization. Psychol. Sci. 21 , 372–374 (2010).

PubMed Google Scholar

Swann, W. B., Pelham, B. W. & Krull, D. S. Agreeable fancy or disagreeable truth? Reconciling self-enhancement and self-verification. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57 , 782–791 (1989).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Sedikides, C. & Gregg, A. P. Self-enhancement food for thought. Perspect. Psychol. Sci . 3 , 102–116 (2008).

Epstein, S. The self-concept: a review and the proposal of an integrated theory of personality. In Personality: Basic aspects and current research (ed Staub, E.) 82–132 (Prentice-Hall, 1980).

Steele, C. M. The psychology of self-affirmation: sustaining the integrity of the self. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 21 , 261–302 (1988).

Swann, W. B. & Ely, R. J. A battle of wills: self-verification versus behavioral confirmation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 46 , 1287 (1984).

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M. & Joseph, S. The authentic personality: a theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the Authenticity Scale. J. Couns. Psychol. 55 , 385–399 (2008).

Article Google Scholar

Newheiser, A. K. & Barreto, M. Hidden costs of hiding stigma: Ironic interpersonal consequences of concealing a stigmatized identity in social interactions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 52 , 58–70 (2014).

Festinger, L. A theory of cognitive dissonance . (Stanford University Press, 1962).

Little, B. R. Free traits and personal contexts: Expanding a social ecological model of well-being. In Person–environment psychology: New directions and perspectives (eds Walsh, W. B., Craik, K. H. & Price, R. H.), 87–116 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2000).

Lecky, P. Self-consistency; a theory of personality . (Island Press, 1945).

Hogan, R. T. Personality and personality measurement. In Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (eds Dunnette, M. D. & Hough, L. M.), 873–919 (Consulting Psychologists Press., 1991).

Ozer, D. J. & Benet-Martinez, V. Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes. Annu. Rev. Psychol . 57 , 401–421 (2006).

Goldberg, L. R. An alternative “description of personality”: the big-five factor structure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol . 59 , 1216–1229 (1990).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Vazire, S. & Gosling, S. D. e-Perceptions: personality impressions based on personal websites. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87 , 123–132 (2004).

Sedikides, C., Lenton, A. P., Slabu, L. & Thomaes, S. Sketching the contours of state authenticity. Rev. Gen. Psychol . https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000156 (2018).

Peterson, R. A. In search of authenticity*. J. Manag. Stud. 42 , 1083–1098 (2005).

Fleeson, W. & Wilt, J. The relevance of big five trait content in behavior to subjective authenticity: do high levels of within-person behavioral variability undermine or enable authenticity achievement? J. Pers . 78 , 1353–1382 (2010).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Jongman-Sereno, K. P. & Leary, M. R. Self-perceived authenticity is contaminated by the valence of One’s behavior. Self Identity 15 , 283–301 (2016).

Kernis, M. H. & Goldman, B. M. A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: theory and research. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 38 , 283–357 (2006).

Hudson, N. W. & Fraley, R. C. Volitional personality trait change: can people choose to change their personality traits? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 109 , 490 (2015).

Hudson, N. W. & Roberts, B. W. Goals to change personality traits: Concurrent links between personality traits, daily behavior, and goals to change oneself. J. Res. Pers . 53 , 68–83 (2014).

Kosinski, M., Matz, S. C., Gosling, S. D., Popov, V. & Stillwell, D. Facebook as a research tool for the social sciences: opportunities, challenges, ethical considerations, and practical guidelines. Am. Psychol. 70 , 543–556 (2015).

Stillwell, D. J. & Kosinski, M. myPersonality project: example of successful utilization of online social networks for large-scale social research. Am. Psychol. 59 , 93–104 (2004).

Youyou, W., Kosinski, M. & Stillwell, D. Computers judge personalities better than humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , 1036–1040 (2015).

ADS PubMed CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Park, G. et al. Automatic personality assessment through social media language. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 108 , 934 (2015).

Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D. & Graepel, T. Private traits and attributes are predictable from digital records of human behavior. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110 , 5802–5805 (2013).

Matz, S. C., Gladstone, J. J. & Stillwell, D. Money buys happiness when spending fits our personality. Psychol. Sci. 27 , 715–725 (2016).

Bailey, E. Authenticity and Well-being | OSF Registries. https://osf.io/njcgs (2020).

Goldberg, L. R. et al. The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. J. Res. Pers. 40 , 84–96 (2006).

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49 , 71–75 (1985).

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Mayer, J. D. & Gaschke, Y. N. The experience and meta-experience of mood. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 55 , 102 (1988).

Swann, W. B., Griffin, J. J., Predmore, S. C. & Gaines, B. The cognitive–affective crossfire: When self-consistency confronts self-enhancement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 52 , 881–889 (1987).

Gentile, B., Twenge, J. M., Freeman, E. C. & Campbell, W. K. The effect of social networking websites on positive self-views: An experimental investigation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 28 , 1929–1933 (2012).

Allcott, H., Braghieri, L., Eichmeyer, S. & Gentzkow, M. The Welfare Effects of Social Media (No. w25514). Natl. Bur. Econ. Res . 110 , 629–676 (2019).

Orben, A. & Przybylski, A. K. The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3 , 173–182 (2019).

Heffer, T., Good, M., Daly, O., MacDonell, E. & Willoughby, T. The longitudinal association between social-media use and depressive symptoms among adolescents and young adults: an empirical reply to Twenge et al. (2018). Clin. Psychol. Sci . https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618812727 (2019).

Verduyn, P. et al. Passive Facebook usage undermines affective well-being: Experimental and longitudinal evidence. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 144 , 480–488 (2015).

Jebb, A. T., Morrison, M., Tay, L. & Diener, E. Subjective well-being around the world: trends and predictors across the life span. Psychol. Sci. 31 , 293–305 (2020).

Diener, E., Diener, M. & Diener, C. Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. In Culture and well-being , 43–70 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2009).

Helliwell, J. F. How’s life? Combining individual and national variables to explain subjective well-being. Econ. Model. 20 , 331–360 (2003).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88 , 879 (2003).

Matz, S. C., Gladstone, J. J. & Stillwell, D. In a world of big data, small effects can still matter: a reply to Boyce, Daly, Hounkpatin, and Wood (2017). Psychol. Sci . 28 , 547–550 (2017).

Wilson, R. E., Gosling, S. D. & Graham, L. T. A review of Facebook research in the social sciences. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7 , 203–220 (2012).

Research, E. & Salesforce. Percentage of U.S. population with a social media profile from 2008 to 2019. In Statista—The Statistics Portal (J. Clement, 2019).

McCrae, R. R. & John, O. P. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. J. Pers. 60 , 175–215 (1992).

Goldberg, L. R. The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychol. Assess. 4 , 26–42 (1992).

McCrae, R. R. & Allik, I. U. The five-factor model of personality across cultures . (Springer Science & Business Media, 2002).

Paunonen, S. V. Big five factors of personality and replicated predictions of behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84 , 411–424 (2003).

Schwartz, H. A. et al. Personality, gender, and age in the language of social media: the open-vocabulary approach. PLoS ONE 8 , e73791 (2013).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Arrindell, W. A., Heesink, J. & Feij, J. A. The satisfaction with life scale (SWLS): appraisal with 1700 healthy young adults in The Netherlands. Pers. Individ. Dif. 26 , 815–826 (1999).

Soto, C. J. & John, O. P. The next big five inventory (BFI-2): developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 113 , 117–143 (2017).

Watson, D., Clark, L. A. & Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54 , 1063 (1988).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Blaine Horton, Jon Jachimowicz, Maya Rossignac-Milon, and Kostadin Kushlev for critical feedback which substantially improved this paper.

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Erica R. Bailey, Sandra C. Matz.

Authors and Affiliations

Columbia Business School, Columbia University, 3022 Broadway, New York, NY, 10027, USA

Erica R. Bailey, Sandra C. Matz & Sheena S. Iyengar

Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, 2211 Campus Dr, Evanston, IL, 60208, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

E.R.B. and S.C.M. developed and designed the research; S.C.M. analyzed the data; E.R.B., S.C.M., W.Y., and S.I. interpreted the data and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Erica R. Bailey .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Daniel Preotiuc-Pietro, Christopher J. Soto and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, peer review file, reporting summary, source data, source data, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bailey, E.R., Matz, S.C., Youyou, W. et al. Authentic self-expression on social media is associated with greater subjective well-being. Nat Commun 11 , 4889 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18539-w

Download citation

Received : 22 July 2019

Accepted : 12 August 2020

Published : 06 October 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18539-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

The mediating effect of social network identity management on the relationship between personality traits and social media addiction among pre-service teachers.

- Onur Isbulan

- Mark D. Griffiths

BMC Psychology (2024)

Umbrella review of meta-analyses on the risk factors, protective factors, consequences and interventions of cyberbullying victimization

- K. T. A. Sandeeshwara Kasturiratna

- Andree Hartanto

- Nadyanna M. Majeed

Nature Human Behaviour (2024)

Distilling the concept of authenticity

- Constantine Sedikides

- Rebecca J. Schlegel

Nature Reviews Psychology (2024)

Adolescent Emotional Expression on Social Media: A Data Donation Study Across Three European Countries

- Kaitlin Fitzgerald

- Laura Vandenbosch

- Toon Tabruyn

Affective Science (2024)

The beauty and the beast of social media: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the impact of adolescents' social media experiences on their mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Betul Keles

- Annmarie Grealish

Current Psychology (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Social Media Use and Mental Health and Well-Being Among Adolescents - A Scoping Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Health Promotion, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Bergen, Norway.

- 2 Alcohol and Drug Research Western Norway, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway.

- 3 Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway.

- PMID: 32922333

- PMCID: PMC7457037

- DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01949

Introduction: Social media has become an integrated part of daily life, with an estimated 3 billion social media users worldwide. Adolescents and young adults are the most active users of social media. Research on social media has grown rapidly, with the potential association of social media use and mental health and well-being becoming a polarized and much-studied subject. The current body of knowledge on this theme is complex and difficult-to-follow. The current paper presents a scoping review of the published literature in the research field of social media use and its association with mental health and well-being among adolescents. Methods and Analysis: First, relevant databases were searched for eligible studies with a vast range of relevant search terms for social media use and mental health and well-being over the past five years. Identified studies were screened thoroughly and included or excluded based on prior established criteria. Data from the included studies were extracted and summarized according to the previously published study protocol. Results: Among the 79 studies that met our inclusion criteria, the vast majority (94%) were quantitative, with a cross-sectional design (57%) being the most common study design. Several studies focused on different aspects of mental health, with depression (29%) being the most studied aspect. Almost half of the included studies focused on use of non-specified social network sites (43%). Of specified social media, Facebook (39%) was the most studied social network site. The most used approach to measuring social media use was frequency and duration (56%). Participants of both genders were included in most studies (92%) but seldom examined as an explanatory variable. 77% of the included studies had social media use as the independent variable. Conclusion: The findings from the current scoping review revealed that about 3/4 of the included studies focused on social media and some aspect of pathology. Focus on the potential association between social media use and positive outcomes seems to be rarer in the current literature. Amongst the included studies, few separated between different forms of (inter)actions on social media, which are likely to be differentially associated with mental health and well-being outcomes.

Keywords: adolescence; mental health; scoping review; social media; well-being.

Copyright © 2020 Schønning, Hjetland, Aarø and Skogen.

Publication types

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Associations between social media use and loneliness in a cross-national population: do motives for social media use matter?

Tore bonsaksen, mary ruffolo, daicia price, janni leung, hilde thygesen, isaac kabelenga, amy østertun geirdal.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Tore Bonsaksen [email protected] Department of Health and Nursing Science, Faculty of Social and Health Science, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, Elverum, Norway

Department of Health, Faculty of Health Studies, VID Specialized University, Stavanger, Norway

Received 2022 Aug 24; Accepted 2022 Dec 5; Collection date 2023.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

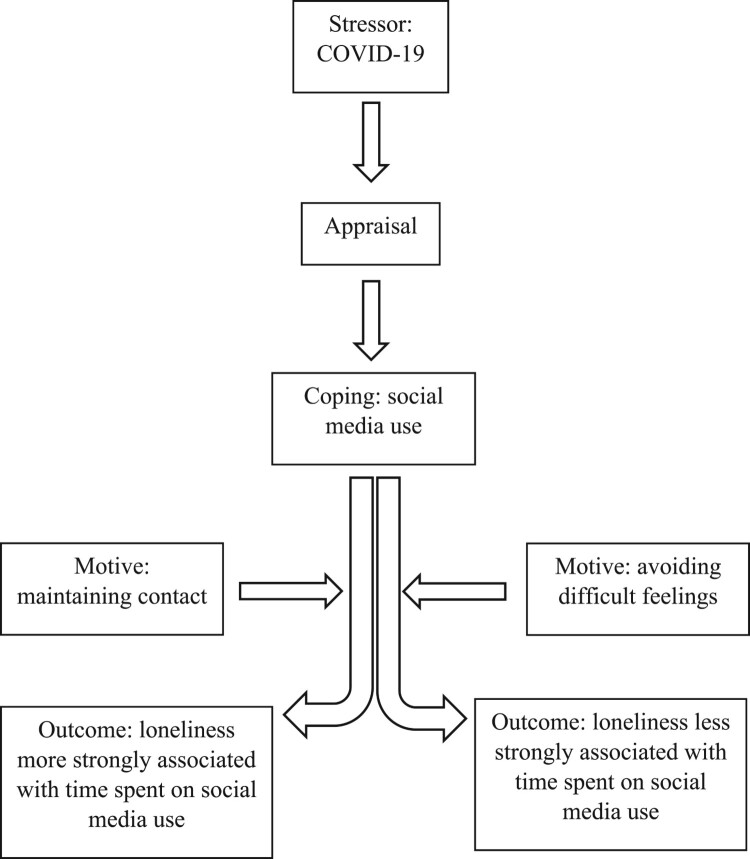

Background: We aimed to examine the association between social media use and loneliness two years after the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Methods: Participants were 1649 adults who completed a cross-sectional online survey disseminated openly in Norway, United Kingdom, USA, and Australia between November 2021 and January 2022. Linear regressions examined time spent on social media and participants’ characteristics on loneliness, and interactions by motives for social media use. Results: Participants who worried more about their health and were younger, not employed, and without a spouse or partner reported higher levels of loneliness compared to their counterparts. More time spent on social media was associated with more loneliness ( β = 0.12, p < 0.001). Three profile groups emerged for social media use motives: 1) social media use motive ratings on avoiding difficult feelings higher or the same as for maintaining contact; 2) slightly higher ratings for maintaining contact; and 3) substantially higher ratings for maintaining contact. Time spent on social media was significant only in motive profile groups 2 and 3 ( β = 0.12 and β = 0.14, both p < 0.01). Conclusions: Our findings suggest that people who use social media for the motive of maintaining their relationships feel lonelier than those who spend the same amount of time on social media for other reasons. While social media may facilitate social contact to a degree, they may not facilitate the type of contact sought by those who use social media primarily for this reason.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, cross-cultural study, loneliness, moderation analysis, social media

Introduction

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown of society resulted in severe disruptions in many aspects of social life. As people were generally instructed to practice ‘social distancing’ to curb the virus transmission (World Health Organization, 2020 ), many restrictions were placed on people’s opportunity to meet other people. Many usual arenas in society for meeting people, such as schools, workplaces, organized leisure, cafes, and restaurants, were temporarily closed, and transportation was restricted (Gostin & Wiley, 2020 ). This situation led to a growing concern about negative mental health effects of the well-intended measures to reduce the viral spread (Kaufman et al., 2020 ; Mi et al., 2020 ).

Loneliness refers to the subjective, distressing experience of having a lack or deficiency in one’s social connection to others, indicating that relationships with others are missing or inadequate (Bekhet et al., 2008 ). Some authors have distinguished between different aspects of loneliness, and subtypes have included social loneliness, referring to having too few people in one’s social network, and emotional loneliness, referring to having a lack of intimacy and attachment in relationships (Dahlberg & McKee, 2014 ; de Jong Gierveld & Van Tilburg, 2010 ; Dykstra & Fokkema, 2007 ). A vast amount of studies have identified loneliness to be an important precursor of mental health problems such as depression (Beutel et al., 2017 ; Lee et al., 2020 ; Luanaigh & Lawlor, 2008 ; Palgi et al., 2020 ; Santini et al., 2016 ; Victor & Yang, 2012 ), anxiety (Beutel et al., 2017 ; Palgi et al., 2020 ) and suicidal ideation and behavior (Beutel et al., 2017 ; Stickley & Koyanagi, 2016 ). Due to the social restrictions during the pandemic, a particular concern was that more people would struggle with loneliness over a longer period of time (Hoffart et al., 2022 ; Luchetti et al., 2020 ; Palgi et al., 2020 ). However, the evidence to support such worries have been mixed. A nationwide study in the USA showed no marked increase in loneliness, but rather a remarkable resilience in the response to the pandemic situation (Luchetti et al., 2020 ). During the first weeks of lockdown in the UK, a study showed relatively high levels of loneliness in the population, but little sign of worsening (Bu et al., 2020 ). In contrast, other studies have shown increasing levels of loneliness in various population subsets during the COVID-19 pandemic (Buecker & Horstmann, 2021 ; Lampraki et al., 2022 ; Lee et al., 2020 ). In view of its importance for the development of mental health problems and disorders, loneliness has been considered a major public health issue during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In situations where stressful events and circumstances are unavoidable, such as during the pandemic, engaging with the community and receiving support from the network can serve as an important way of coping with stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984 ; Zacher & Rudolph, 2021 ). However, adherence to the social distancing regulations during the pandemic meant that the typical ways of coping by engaging with others – being together in smaller or larger groups – were difficult to use. Reduced access to other people that typically provide social support and enhance resiliency might significantly affect people’s usual coping strategies and therefore leave individuals more vulnerable to experiencing loneliness.

Since their inception, social media have become widely adopted in people’s everyday lives (Boulianne, 2015 ; Chou et al., 2009 ). Further, with the limited abilities to connect with others in person during social distancing and isolation mandates, social media have been increasingly used for connecting people in work, learning, and social interactions (Gao et al., 2020 ; Palgi et al., 2020 ; Wiederhold, 2020 ). However, the role of social media for people’s mental health and wellbeing is disputed. While some studies have shown that social media allow people to maintain their social relationships, thereby representing one way of coping with loneliness and distress (Cauberghe et al., 2021 ; Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2003 ; Nowland et al., 2018 ; Thomas et al., 2020 ), other studies have found higher levels of social media use to be associated with poorer mental health (Gao et al., 2020 ; Geirdal, Ruffolo, et al., 2021 ) and higher levels of loneliness (Bonsaksen, Schoultz, et al., 2021 ; Helm et al., 2022 ). Thus, the coping potential of social media use to mitigate stress, is unclear.

Experimental research has shown that students whose social media use was limited to 10 min per day over a three week period experienced significant reductions in depression and loneliness, compared to control group participants who used social media without restriction (Hunt et al., 2018 ). Further, associations between social media use and mental health outcomes may vary by a range of other factors. For example, a previous study found that older people (60 + years of age) using more types of social media experienced lower levels of social loneliness, whereas younger people (18–39 years of age) using more types of social media experienced higher levels of emotional loneliness (Bonsaksen, Ruffolo, et al., 2021 ). Such findings increase the complexity of this picture, demonstrating that associations may depend on participant characteristics, which aspect of social media use is considered, as well as nuances in the employed outcome measures.

Time spent using social media during a defined time interval is often used as a measure of social media use. However, a wide range of social media measures is used in research. While varied measurement methods may contribute to ambiguity in the interpretation of research findings (Petropoulos Petalas et al., 2021 ), they may also be useful for addressing aspects of social media use that are otherwise left unexplored. One line of research has focused on people’s motives for using social media, and a previous study found that using Facebook for making new friends reduced loneliness, whereas using Facebook for social skills compensation increased loneliness (Teppers et al., 2014 ). Similarly, a recent study found that dissimilar motives for social media use were differently associated with mental health (Thygesen et al., 2022 ). Higher ratings on the ‘personal contact’ and ‘maintaining relationships’ motives for using social media were associated with better mental health, while higher ratings on the ‘decrease loneliness’ and ‘entertainment’ motives were associated with poorer mental health. Intrapersonal motives for social media use, including the desire to forget complications of everyday life and to pass time, have also been found to be the most important predictor for problematic social media use (Schivinski et al., 2020 ).

The world continues to respond to the pandemic, via vaccination roll out, lock downs and restrictions on travel. Years after the initial onset of the pandemic it is possible that associations between social media use and mental health outcomes – including loneliness – are different from what they were in the early stages. Such changes may be due to lifted restrictions on social interaction, new waves of virus transmission, having adapted to a new lifestyle, or a combination of these and other contributing factors. In addition, previous results concerned with the significance of motives for social media use justify exploring whether the association between time on social media and loneliness depend on the motives people have for using social media. Considering motives for engaging with social media may provide nuance to our understanding of how social media use relates to loneliness. In addition, it may contribute to specifying some of the conditions moderating the coping potential related to using social media during the stressful COVID-19 pandemic.

Aim of the study

The aim of the study was to examine the association between daily time on social media and loneliness in a cross-national population two years after the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, and to examine any moderation effect of motives for social media use. The research questions were:

What is the nature of the association between time spent on social media use and loneliness, as measured two years after the COVID-19 outbreak?

Do motives for social media use moderate the association between time spent on social media use and loneliness during the same period?

The study reports from the third cross-sectional online survey disseminated openly by social media (i.e. Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter) in four countries (Norway, United Kingdom [UK], USA, and Australia) during the COVID-19 pandemic. This survey was open for the adult (≥ 18 years of age) general public’s participation between November 2021 and January 2022, while the two previous surveys were administered in April/May 2020 and in November 2020, respectively.

The total number of participants was 1649, with 242 (14.7%) from Norway, 255 (15.15%) from the UK, 915 (55.5%) from the USA, and 237 (14.4%) from Australia. The age distribution showed that 42% of the participants were under the age of 40 years, 43% between 40 and 59 years, and 15% were 60 years or older. Women comprised the larger part of the sample (75%), while there were 336 (20%) men. Seventy-one (4%) identified their gender as ‘other’ or preferred not to respond to the question, and due to small cell sizes, these individuals were removed from all analyses where the gender variable was included.

An overview of all variables used in the study is shown in Table 1 .

. Overview of all variables used in the study.

Outcome variable

The Loneliness Scale (de Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, 2006 ) consists of six statements, all of which are rated from 0 (totally disagree) to 4 (totally agree). There are two different uses of the instrument. It is possible to construct two different scales, namely social loneliness (e.g. ‘There are plenty of people I can rely on when I have problems’) and ‘emotional loneliness’ (e.g. ‘I experience a general sense of emptiness’) (Bonsaksen et al., 2018 ; de Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, 2006 ). However, including all items to construct a one-factor scale measuring loneliness as one overarching concept is also commonly used (Geirdal, Price, et al., 2021 ), and provided that we required an overall measure of loneliness, we used the one-factor approach in this study. Items with positive phrasing (e.g. having people to rely on) were reverse coded prior to analysis. Cronbach’s α for the scale items was 0.83 indicating strong reliability. The score range was 0–24 with higher scores indicating higher levels of loneliness.

Main predictor variables

Daily social media use.

The participants were asked to indicate the amount of time they had spent on social media on a typical day during the last month. In line with the work of Ellison and co-workers ( 2007 ), response options were less than 10 min (1), 10–30 min (2), 31–60 min (3), 1–2 h (4), 2–3 h (5), and more than three hours (6).

Motives for social media use

The participants were also asked about seven possible motives for using social media. These questions were adapted to a more general form based on Teppers and colleagues ( 2014 ) whose study was concerned with one particular social media. The items were phrased: ‘Nowadays I use social media … ’ with the following endings: ‘to feel involved with what’s going on with other people’ (personal contact motive), ‘because it makes me feel less lonely’ (decrease loneliness motive), ‘so I don’t get bored’ (entertainment motive), ‘to keep in contact with my friends’ (maintaining relationships motive), ‘because I dare say more’ (social skills compensation motive), ‘to be a member of something’ (social inclusion motive), and ‘to make new friends’ (meeting people motive). Response options for these items were never (1), seldom (2), sometimes (3), often (4) and very often (5).

One previous study showed that ratings on motives were differently associated with mental health (Thygesen et al., 2022 ). Specifically, the personal contact and maintaining relationships motives for using social media were associated with better mental health, while the ‘decrease loneliness’ and ‘entertainment’ motives were associated with poorer mental health. Thus, we focused on these two motives. The sum of the ‘personal contact’ and ‘maintaining relationships’ motives was used as a measure of maintaining contact motives, while the sum of the ‘decrease loneliness’ and ‘entertainment’ motives was used as a measure of avoiding difficult feelings motives. The items included on each of the scales correlated well ( r = 0.53, p < 0.001 and r = 0.40, p < 0.001, respectively).

To categorize profiles of motives, a new variable was constructed as the difference between the participants’ ratings on the maintaining contact and the avoiding difficult feelings motive. Based on the distribution of this variable, three similarly large profile groups were identified by using the visual binning procedure with two cut-points. Motive profile group 1 ( n = 686, 41.6%) rated the avoiding difficult feelings items higher or the same as the maintaining contact items. Motive profile group 2 ( n = 589, 35.7%) had slightly higher ratings (1 or 2 point difference) on the maintaining contact items than on the avoiding difficult feelings items, while motive profile group 3 ( n = 374, 22.7%) had substantially higher ratings (3 point difference or more) on the maintaining contact items than on the avoiding difficult feelings items.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic variables included country (Norway UK, USA, Australia), age group (18–39, 40–59, 60 and above), gender, education level (lower vs bachelor’s degree or higher), employment status (yes/no), and having a spouse/partner (yes/no).

Health worry

The participants were asked to rate their level of worry about their own health on one item. The item had the following response options: (1) not at all, (2) a bit, (3) pretty much, (4) very much, and (5) extremely.

Comparisons between two groups were made using the independent t -test, while comparisons between several groups were made using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Bivariate associations between continuous variables were examined with Pearson’s correlation coefficient r . Linear multiple regression analysis was used to examine adjusted associations between each of the independent variables and loneliness. An interaction term was included to examine whether the association between social media use and loneliness varied by motive profiles. Independent variables were entered in three blocks: (1) age group, spouse/partner, employment, and health worry; (2) daily time on social media; and (3) daily time on social media × motive profile group. If the interaction term was statistically significant, separate analyses were performed for each of the motive profile groups. Effect sizes are reported as standardized beta weights β , and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Missing data were removed from the analyses by casewise deletion. In preparation for the multivariate linear regression analysis, multicollinearity was checked with the variance inflation factor (VIF) (Hocking, 2013 ). All VIFs were between 1.02 and 1.12, indicating no problematic multicollinearity between the independent variables. While the distribution of loneliness scores deviated from the normal distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test p < 0.001), this has been found to be common in large public health datasets without compromising the validity of parametric test results (Lumley et al., 2002 ). In addition, the loneliness variable showed only minor skewness (0.32, SE = 0.06), well within the recommended interval (George & Mallery, 2010 ). However, the standardized residuals of the dependent variable (between – 2.39 and 3.19) just exceeded the upper range of the recommended interval (i.e. between – 3 and 3) (Field, 2013 ), indicating a need for a cautious interpretation of the regression results.

The study was conducted after receiving ethical approval from the following review boards: OsloMet (20/03676) and the regional committees for medical and health research ethics (REK; ref. 132066) in Norway, reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board for Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences (IRB HSBS) and designated as exempt (HUM00180296) in USA, by Northumbria University Health Research Ethics (HSR1920-080) and University of Central Lancashire (Health Ethics Review Panel) (HEALTH 0246) in the UK, and by The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committees in Australia (HSR1920-080 2020000956).

Loneliness in sample subgroups

Table 2 displays the levels of loneliness in the sample subgroups with significance tests of differences. Participants from Norway reported lower levels of loneliness compared to participants from the other three countries. Participants who were younger, not employed, and without a spouse or partner reported higher levels of loneliness compared to their counterparts. There were no differences according to gender or education level.

. Loneliness in sample subgroups.

Note. Unless otherwise noted, n = 1649 included in all analyses.

Association between social media use and loneliness

Table 3 displays the results from the multiple linear regression analysis with the total sample. Adjusted for age, spouse/partner, employment and health worry, more time spent on social media was associated with more loneliness ( β = 0.12, p < 0.001). Having a spouse or partner and having employment were associated with lower levels of loneliness, while higher levels of health worry was associated with higher levels of loneliness. Unadjusted associations between the study variables are displayed in Appendix 1.

. Linear regression analysis displaying adjusted associations with loneliness.

Note. n = 1649 for all analyses.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

*** p < 0.001

Moderation analysis

The interaction between time on social media and motive profile included in Model 3 ( Table 3 ) was significant, so we proceeded with separate analyses for each of the three motive profile groups. The results are shown in Table 4 . For the participants in motive profile group 1 (social media use motive ratings on avoiding difficult feelings higher or the same as for maintaining contact ), time spent on social media was not significantly associated with loneliness. For the participants in motive profile groups 2 and 3 (slightly, and substantially, higher ratings of using social media for maintaining contact , respectively), more time spent on social media was associated with higher levels of loneliness ( β = 0.12 and 0.14, respectively; both p < 0.001).

. Linear regression analysis displaying adjusted associations with loneliness by motive profile.