| | UK and possibly other pronunciationsUK and possibly other pronunciations/ˈprɛzənts/ | | | | | |

WordReference English Thesaurus © 2024

Adjective: current , contemporary , existing , living , modern , immediate , instant , in existence, existent, present-day, latter-day , finished , in the past, done and dusted (informal), dated , old-fashioned , archaic, historical , early , future , forthcoming , approaching Adjective: existing in space , right here, in the vicinity, at hand, to hand, within reach, available , close , close by, nearby , near , close to home , faraway, remote , out of reach, away , miles away, afar, in the distance, out of sight Noun: present time - preceded by 'the' , the present time, now , today , this moment, this very moment, this time, these days, this day and age, nowadays , distant past, yesterday , last week, a few months ago, years ago, way back Noun: gift , donation, offering , birthday present, Christmas present, Christmas gift, freebie (informal), pressie (UK, slang), prezzie (UK, slang), reward , handout , contribution , curse , dirty trick, prank , liability , junk , cast-off, hand-me-down Verb: give , award , grant , bestow, confer , hand out, hand over, afford , gift , give out, distribute , furnish , provide , receive , take back, take away, confiscate, deny , refuse , deprive , seize , recall , strip sb of sth Verb: display , show , show off, showcase , display , depict , launch , parade , put sth on display, put sth on show, put sth out there (informal), expose , demonstrate , demo (informal), flash , brandish, wield , flaunt, trot out (informal) , cover , conceal , hide , pack , put away Verb: introduce , host , anchor , be the presenter of, be the host of, MC, emcee, announce, give an introduction , forget to introduce Verb: submit , put forward, put forth, put out, offer , proffer, share , hold , keep , retract Verb: stage a performance , perform , stage , mount , act out, act , do , pull out, call off, rehearse , practice Verb: suggest , pose , raise , throw up (informal), suggest , intimate , hint at , not give any clues, deny , suppress , conceal , hide , cover up

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

- English Only forum

Go to page and choose from different actions for taps or mouse clicks. Translations: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Advertisements | | | | Advertisements | | | | | | | | | | | | use for the fastest search of WordReference. | | © 2024 WordReference.com | any problems. | - AI Content Shield

- AI KW Research

- AI Assistant

- SEO Optimizer

- AI KW Clustering

- Customer reviews

- The NLO Revolution

- Press Center

- Help Center

- Content Resources

- Facebook Group

Present Synonym Guide: Definition and ExamplesTable of Contents Synonyms are words with the same meaning as another. They allow you to avoid continually saying the same term. Can you think of any synonyms for “present”? Sometimes the first term that comes to mind may not be the finest; therefore, a guide might help you locate a suitable alternative. Here is a list of present synonyms , their root words, and key examples. This guide will enhance your grammar and word choice whenever you need to use the word present verbally or in writing.   What Does Present Mean?Present means existing or taking place at this very moment. Present also means someone or anything that is at a particular location. In another vein, present could mean to give someone a gift or formally give away something. E.g., I present the global choice award for the best-dressed category. Sentence examples of present- Can we please leave the past and look at the present challenge?

- Hand over the present .

- She will view the present situation and give feedback once she arrives.

Present Synonym: Exploring Words with Similar MeaningsCurrent is an excellent synonym of present. Current indicates that something is occurring, being used, or being performed at present. The term ‘current’ means ‘anticipated to occur within a year or less.’ Current denotes “presently in effect” in the mid-15c. It meant “prevalent, generally reported or known” in the 1560s and “established by common consent” in the 1590s. Examples of sentences with current- Mary is related to my current partner.

- The current state of affairs is nothing to write home about.

- Does your current income meet your needs?

ContemporaryContemporary refers to ‘occurring, being, residing, or coming into existence all throughout the same span of time.’ People and objects from the same era are said to be contemporary with one another. Things that are happening now or just lately can also be considered contemporary. It was first recorded in the 1630s and meant “occurring, living, or existing at the same time, and belonging to the same age or period.” It stems from Medieval Latin contemporarius. Examples of sentences with contemporary- Contemporary artists were not selected to play for his 100th birthday ceremony.

- How unique is contemporary poetry?

- Contemporary artworks are a present beauty to behold.

Nowadays can serve as a great alternative to present. Nowadays is short for “at the present time,” in contrast to “the days of old” or “the olden days.” The term ‘nowadays’ refers to the present period or something occurring at the present moment. Nou adayes was contracted from Middle English in the late 14c and meant “in these times, at the present.” Examples of sentences with nowadays- Nowadays , women are present and more vocal in politics.

- In the past, Kidnapping wasn’t a thing, unlike nowadays .

- Nowadays, everybody has an opinion; even fools are now advisors.

Present is one of many synonyms to say that something is happening now or something is currently occurring. Antonyms and synonyms can be used in various ways to improve the readability of a piece of writing. Make each grammar day count by utilizing a thesaurus or dictionary to build your vocabulary.  Pam is an expert grammarian with years of experience teaching English, writing and ESL Grammar courses at the university level. She is enamored with all things language and fascinated with how we use words to shape our world. Explore All Synonyms ArticlesHappen synonym guide — definition, antonyms, and examples. Are you looking to use happen synonym examples to spice up your writing? That’s not surprising. As a writer, it’s… For Example Synonym Guide — Definition, Antonyms, and ExamplesOne of the best things you can do to improve as a writer is memorize the synonyms of your favorite… Expectations Synonym Guide — Definition, Antonyms, and ExamplesIf you’re looking to use expectations synonym examples in your writing, you’re in luck. This article explores the various similar… Environment Synonym Guide — Definition, Antonyms, and ExamplesIf you’re looking to use environment synonym examples in your writing, you’re in luck. This article explores the various synonyms… Effective Synonym Guide — Definition, Antonyms, and ExamplesIf you’re looking to use effective synonym examples in your writing, you’re in luck. This article explores the various synonyms… Discuss Synonym Guide — Definition, Antonyms, and ExamplesAs a writer, you should understand the essence of studying the synonyms of your favorite words. By doing so, you… Have a language expert improve your writingRun a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free. - Knowledge Base

- The four main types of essay | Quick guide with examples

The Four Main Types of Essay | Quick Guide with ExamplesPublished on September 4, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023. An essay is a focused piece of writing designed to inform or persuade. There are many different types of essay, but they are often defined in four categories: argumentative, expository, narrative, and descriptive essays. Argumentative and expository essays are focused on conveying information and making clear points, while narrative and descriptive essays are about exercising creativity and writing in an interesting way. At university level, argumentative essays are the most common type. | Essay type | Skills tested | Example prompt | | | | Has the rise of the internet had a positive or negative impact on education? | | | | Explain how the invention of the printing press changed European society in the 15th century. | | | | Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself. | | | | Describe an object that has sentimental value for you. | In high school and college, you will also often have to write textual analysis essays, which test your skills in close reading and interpretation. Instantly correct all language mistakes in your textUpload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes  Table of contentsArgumentative essays, expository essays, narrative essays, descriptive essays, textual analysis essays, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about types of essays. An argumentative essay presents an extended, evidence-based argument. It requires a strong thesis statement —a clearly defined stance on your topic. Your aim is to convince the reader of your thesis using evidence (such as quotations ) and analysis. Argumentative essays test your ability to research and present your own position on a topic. This is the most common type of essay at college level—most papers you write will involve some kind of argumentation. The essay is divided into an introduction, body, and conclusion: - The introduction provides your topic and thesis statement

- The body presents your evidence and arguments

- The conclusion summarizes your argument and emphasizes its importance

The example below is a paragraph from the body of an argumentative essay about the effects of the internet on education. Mouse over it to learn more. A common frustration for teachers is students’ use of Wikipedia as a source in their writing. Its prevalence among students is not exaggerated; a survey found that the vast majority of the students surveyed used Wikipedia (Head & Eisenberg, 2010). An article in The Guardian stresses a common objection to its use: “a reliance on Wikipedia can discourage students from engaging with genuine academic writing” (Coomer, 2013). Teachers are clearly not mistaken in viewing Wikipedia usage as ubiquitous among their students; but the claim that it discourages engagement with academic sources requires further investigation. This point is treated as self-evident by many teachers, but Wikipedia itself explicitly encourages students to look into other sources. Its articles often provide references to academic publications and include warning notes where citations are missing; the site’s own guidelines for research make clear that it should be used as a starting point, emphasizing that users should always “read the references and check whether they really do support what the article says” (“Wikipedia:Researching with Wikipedia,” 2020). Indeed, for many students, Wikipedia is their first encounter with the concepts of citation and referencing. The use of Wikipedia therefore has a positive side that merits deeper consideration than it often receives. Receive feedback on language, structure, and formattingProfessional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on: - Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example  An expository essay provides a clear, focused explanation of a topic. It doesn’t require an original argument, just a balanced and well-organized view of the topic. Expository essays test your familiarity with a topic and your ability to organize and convey information. They are commonly assigned at high school or in exam questions at college level. The introduction of an expository essay states your topic and provides some general background, the body presents the details, and the conclusion summarizes the information presented. A typical body paragraph from an expository essay about the invention of the printing press is shown below. Mouse over it to learn more. The invention of the printing press in 1440 changed this situation dramatically. Johannes Gutenberg, who had worked as a goldsmith, used his knowledge of metals in the design of the press. He made his type from an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony, whose durability allowed for the reliable production of high-quality books. This new technology allowed texts to be reproduced and disseminated on a much larger scale than was previously possible. The Gutenberg Bible appeared in the 1450s, and a large number of printing presses sprang up across the continent in the following decades. Gutenberg’s invention rapidly transformed cultural production in Europe; among other things, it would lead to the Protestant Reformation. A narrative essay is one that tells a story. This is usually a story about a personal experience you had, but it may also be an imaginative exploration of something you have not experienced. Narrative essays test your ability to build up a narrative in an engaging, well-structured way. They are much more personal and creative than other kinds of academic writing . Writing a personal statement for an application requires the same skills as a narrative essay. A narrative essay isn’t strictly divided into introduction, body, and conclusion, but it should still begin by setting up the narrative and finish by expressing the point of the story—what you learned from your experience, or why it made an impression on you. Mouse over the example below, a short narrative essay responding to the prompt “Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself,” to explore its structure. Since elementary school, I have always favored subjects like science and math over the humanities. My instinct was always to think of these subjects as more solid and serious than classes like English. If there was no right answer, I thought, why bother? But recently I had an experience that taught me my academic interests are more flexible than I had thought: I took my first philosophy class. Before I entered the classroom, I was skeptical. I waited outside with the other students and wondered what exactly philosophy would involve—I really had no idea. I imagined something pretty abstract: long, stilted conversations pondering the meaning of life. But what I got was something quite different. A young man in jeans, Mr. Jones—“but you can call me Rob”—was far from the white-haired, buttoned-up old man I had half-expected. And rather than pulling us into pedantic arguments about obscure philosophical points, Rob engaged us on our level. To talk free will, we looked at our own choices. To talk ethics, we looked at dilemmas we had faced ourselves. By the end of class, I’d discovered that questions with no right answer can turn out to be the most interesting ones. The experience has taught me to look at things a little more “philosophically”—and not just because it was a philosophy class! I learned that if I let go of my preconceptions, I can actually get a lot out of subjects I was previously dismissive of. The class taught me—in more ways than one—to look at things with an open mind. A descriptive essay provides a detailed sensory description of something. Like narrative essays, they allow you to be more creative than most academic writing, but they are more tightly focused than narrative essays. You might describe a specific place or object, rather than telling a whole story. Descriptive essays test your ability to use language creatively, making striking word choices to convey a memorable picture of what you’re describing. A descriptive essay can be quite loosely structured, though it should usually begin by introducing the object of your description and end by drawing an overall picture of it. The important thing is to use careful word choices and figurative language to create an original description of your object. Mouse over the example below, a response to the prompt “Describe a place you love to spend time in,” to learn more about descriptive essays. On Sunday afternoons I like to spend my time in the garden behind my house. The garden is narrow but long, a corridor of green extending from the back of the house, and I sit on a lawn chair at the far end to read and relax. I am in my small peaceful paradise: the shade of the tree, the feel of the grass on my feet, the gentle activity of the fish in the pond beside me. My cat crosses the garden nimbly and leaps onto the fence to survey it from above. From his perch he can watch over his little kingdom and keep an eye on the neighbours. He does this until the barking of next door’s dog scares him from his post and he bolts for the cat flap to govern from the safety of the kitchen. With that, I am left alone with the fish, whose whole world is the pond by my feet. The fish explore the pond every day as if for the first time, prodding and inspecting every stone. I sometimes feel the same about sitting here in the garden; I know the place better than anyone, but whenever I return I still feel compelled to pay attention to all its details and novelties—a new bird perched in the tree, the growth of the grass, and the movement of the insects it shelters… Sitting out in the garden, I feel serene. I feel at home. And yet I always feel there is more to discover. The bounds of my garden may be small, but there is a whole world contained within it, and it is one I will never get tired of inhabiting. Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading servicesDiscover proofreading & editing Though every essay type tests your writing skills, some essays also test your ability to read carefully and critically. In a textual analysis essay, you don’t just present information on a topic, but closely analyze a text to explain how it achieves certain effects. Rhetorical analysisA rhetorical analysis looks at a persuasive text (e.g. a speech, an essay, a political cartoon) in terms of the rhetorical devices it uses, and evaluates their effectiveness. The goal is not to state whether you agree with the author’s argument but to look at how they have constructed it. The introduction of a rhetorical analysis presents the text, some background information, and your thesis statement; the body comprises the analysis itself; and the conclusion wraps up your analysis of the text, emphasizing its relevance to broader concerns. The example below is from a rhetorical analysis of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech . Mouse over it to learn more. King’s speech is infused with prophetic language throughout. Even before the famous “dream” part of the speech, King’s language consistently strikes a prophetic tone. He refers to the Lincoln Memorial as a “hallowed spot” and speaks of rising “from the dark and desolate valley of segregation” to “make justice a reality for all of God’s children.” The assumption of this prophetic voice constitutes the text’s strongest ethical appeal; after linking himself with political figures like Lincoln and the Founding Fathers, King’s ethos adopts a distinctly religious tone, recalling Biblical prophets and preachers of change from across history. This adds significant force to his words; standing before an audience of hundreds of thousands, he states not just what the future should be, but what it will be: “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.” This warning is almost apocalyptic in tone, though it concludes with the positive image of the “bright day of justice.” The power of King’s rhetoric thus stems not only from the pathos of his vision of a brighter future, but from the ethos of the prophetic voice he adopts in expressing this vision. Literary analysisA literary analysis essay presents a close reading of a work of literature—e.g. a poem or novel—to explore the choices made by the author and how they help to convey the text’s theme. It is not simply a book report or a review, but an in-depth interpretation of the text. Literary analysis looks at things like setting, characters, themes, and figurative language. The goal is to closely analyze what the author conveys and how. The introduction of a literary analysis essay presents the text and background, and provides your thesis statement; the body consists of close readings of the text with quotations and analysis in support of your argument; and the conclusion emphasizes what your approach tells us about the text. Mouse over the example below, the introduction to a literary analysis essay on Frankenstein , to learn more. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, protagonist Victor Frankenstein is a stable representation of the callous ambition of modern science throughout the novel. This essay, however, argues that far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as. This essay begins by exploring the positive portrayal of Frankenstein in the first volume, then moves on to the creature’s perception of him, and finally discusses the third volume’s narrative shift toward viewing Frankenstein as the creature views him. If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools! - Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays - Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools - Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

At high school and in composition classes at university, you’ll often be told to write a specific type of essay , but you might also just be given prompts. Look for keywords in these prompts that suggest a certain approach: The word “explain” suggests you should write an expository essay , while the word “describe” implies a descriptive essay . An argumentative essay might be prompted with the word “assess” or “argue.” The vast majority of essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Almost all academic writing involves building up an argument, though other types of essay might be assigned in composition classes. Essays can present arguments about all kinds of different topics. For example: - In a literary analysis essay, you might make an argument for a specific interpretation of a text

- In a history essay, you might present an argument for the importance of a particular event

- In a politics essay, you might argue for the validity of a certain political theory

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way. An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research. The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept. Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays , and similar writing skills can apply to both. Cite this Scribbr articleIf you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator. Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). The Four Main Types of Essay | Quick Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/essay-types/ Is this article helpful? Jack CaulfieldOther students also liked, how to write an argumentative essay | examples & tips, how to write an expository essay, how to write an essay outline | guidelines & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..". I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes” Synonyms for "showing"/"presenting"? English Lit GCSEQuick reply, related discussions. - Official Year 11 Chat Thread 2024-25

- English language GCSE

- My year 11 journey

- Grade 9 answers (English Lit)

- English Literature

- Grade 9 in english literature??

- Help on PQA (Point, Quote, Analysis)

- I need help on my inspector calls essay

- What is OCR English lit like at A level

- Is anyone able to mark my AQA GCSE essay on a Christmas carol?

- gcse advice

- please help A christmas carol

- Grade 9 in English Literature

- Going from a C to A in english lit A-level

- HOW to study

- gcse english lit quotes

- english literature

- A level English lit help

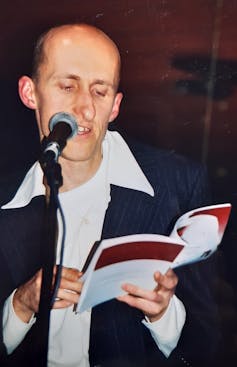

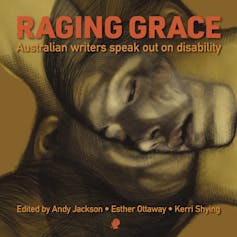

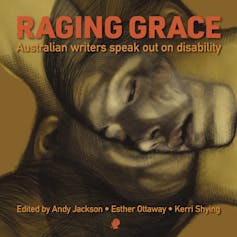

Last reply 10 hours ago Last reply 19 hours ago Last reply 1 day ago Last reply 4 days ago Last reply 5 days ago Last reply 1 week ago Last reply 3 weeks ago Articles for you What happens if you need help at university? Top 10 tips for Ucas Clearing 2024  Bringing business people into the classroom: what students learn from industry professionals  Will artificial intelligence put legal graduates out of work? Try out the app Continue on web  Friday essay: ‘I know my ache is not your pain’ – disabled writers imagine a healthier world Creative Writing Lecturer, The University of Melbourne Disclosure statementAndy Jackson received funding from RMIT University under their Writing the Future of Health Fellowship. University of Melbourne provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU. View all partners There are many reasons why I shouldn’t be here. If you’d shown my ten-year-old self my life as it is now, he’d have been stunned, mostly because he half-expected an early death. My father, who had Marfan Syndrome , the genetic condition I have, died when he was in his mid-40s, when I was two, and the conventional medical wisdom of the time was that this was normal, almost expected. Marfan is known as a “disorder of connective tissue”, meaning numerous systems of the body can be affected – the connective tissue of the heart, joints, eyes are liable to strain or tear. In my teens, I had multiple spinal surgeries, but there was always the spectre of sudden aortic dissection: a potentially life-threatening tear in the aorta, the body’s largest blood vessel. Like walking around under a storm cloud, never knowing if or when the lightning would strike. If you’d shown my 20-year-old self my life now, he’d have said, well, I’m not disabled, not really, I mean, I’m not disadvantaged by my body, there’d be other people who really are. At that age, I felt profoundly stigmatised, faltering under the weight of other people’s intrusive attention, a different kind of lightning, that kept striking.  My sense back then was that disability was about impairment. They use wheelchairs. They’re blind or deaf. They’re intellectually disabled. Not me. I just had a differently shaped body, which was other people’s problem, not mine. As if I could keep those things discreet. Back then, in the films, television dramas and books I consumed, there were disabled characters, invariably marginal or two-dimensionally pathetic or tragic. Their existence was functional, a resource to be mined. Their bodies were metaphorically monumental, looming over the narrative, yet somehow hollow, without the fullness of agency. I certainly didn’t know any disabled authors. This is an edited extract of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature Patron’s Lecture, delivered at UniSA Creative’s Finding Australia’s Disabled Authors online symposium on Wednesday 25 September. Becoming a writer within a communityMy 35-year-old self would mostly be surprised at the distance I’ve travelled as a writer. From open mic poetry nights in Fitzroy and Brunswick, via publication in photocopied zines and established literary journals, onto my first book of poems (then more), grants, residencies, a PhD in disability poetics, the Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Poetry – and now teaching creative writing at the University of Melbourne. These, of course, are only the outward markers. What’s most potent for me is the sense that, in spite of my ongoing sense of dislocation and marginality, I do belong within a net of support and meaning-making.  I’m part of a community of poets and writers. A community of disabled people and people with disabilities, people who know chronic illness, the flux of mental health, who know what it’s like to be othered. I also live as a non-Indigenous person on Dja Dja Wurrung country, whose elders have cared for their land, kept culture alive, and resisted colonisation and its brutal extractions. An awareness of where we are situated, a felt sense of relationship with others like and unlike us, a consciousness of the histories and political forces that shape us, a hunch that our woundedness is not separate from the woundedness of the entire biosphere: none of this just happens automatically, though it emerges from a very subtle inner resonance. It has to be attended to, nurtured with curiosity and empathy, within a community. Because disability – as a socially-constructed reality, and as an identity that is claimed – is not essentially a category, but a centre of gravity every body is drawn towards. This may not be the conception of disability you’re used to. Disability as human experienceThe social model of disability is the idea that what makes someone disabled are the social, political, medical, institutional, architectural and cultural forces and structures. Stairs (for people using wheelchairs) and stares (for those who look, or move, or talk in a non-normative way, where normal is a kind of Platonic abstraction of what humans ought to be). But disability is also a fundamental aspect of human experience, with its own magnetism or impersonal charisma. Disability is an unavoidable bedrock of being alive.  There is a tension here, of course. Between disability as a dimension of discrimination, which creates barriers we want to dismantle, and disability as an inherent aspect of an embodiment that is precarious, mortal and relational. I am here because some of the barriers that impeded me have been, if not removed, then softened, weakened. Shame, stigma, an internalised sense of being less-than, abnormal, sub-normal: these things are being slowly eroded. Not, fundamentally, through any great effort on my part, but through the accumulated efforts and energies of communities that have gone before me, and that exist around me. How can we best flourish?In late 2021, the Health Transformation Lab at RMIT University announced their Writing the Future of Health Fellowship . The successful writer would be paid for six months to work on a project of their choice. The call for applications emphasised innovation, creativity and collaboration. It invited a Melbourne writer to address the question: what does the future of health look like?  I proposed a collaboration: an anthology of poems, essays and hybrid pieces by disabled writers. It will be published next week, as Raging Grace: Australian Writers Speak Out on Disability . I applied for the fellowship less than a year after the devastations of Australia’s Black Summer bushfires of 2019. Loss of lives, homes and livelihoods. Billions of animals dead or displaced. Smoke blanketed the sky and the trauma of it blanketed our lives. Then came COVID-19, which would kill millions worldwide. Its overwhelming burden was on poor and disabled bodies. In Australia, 2020 was the year of lockdowns, social distancing and mask mandates, then vaccination, hope, resentment, disinformation, fear, fatigue. Quite quickly, it seems in retrospect, the talk was of “opening up”, “learning to live with it”. “The new normal” switched to “back to normal”. Everything felt scorched, fraught, ready to ignite again.  Those of us with experience of disability, neurodivergent people, those who live with chronic illness, depression, anxiety, trauma (I could go on) – we have unique and profound expertise on what health actually is, in the deepest sense, and what kind of environments allow us to survive and flourish. The future of health, for all of us, I felt, depended on the health systems and the wider society being diagnosed by disabled people. It depended on us being integrally involved in imagining genuinely therapeutic futures. ‘An almost utopian daydream’My fellowship pitch was an almost utopian daydream: collective empowerment and imagination in an era of crisis, precarity and isolation. What the project required was a community: diverse and open to each other. I wanted a range of personal and bodily experiences, places of residence, cultural backgrounds, genders, sexualities and ages. In the end, a collective of 23 writers coalesced – poets, essayists, memoirists, thinkers, activists and community workers, but, above all, writers. All of us in this project have first-hand experience of disability, neurodivergence, chronic pain and/or mental illness. The labels mean something, but we’re much larger than them. Men, women, non-binary folk; people of varying ages and cultural backgrounds, some First Nations, most not; queer, straight, cis, not; shy, vociferous, uncertain, confident, tired, in flux. People from many different corners of this continent.  Throughout 2022, we met in person and online. I called these meetings “workshops”. We looked at poems and essays together, thinking through the music and the bodily energies of the language. But these were really conversations: minimally guided, intensely honest and free-flowing conversations about what we have experienced, and what we know about how society creates and exacerbates disability. We diagnosed the systems (health, bureaucratic, economic), and daydreamed utopian and practical therapeutic futures. In the process, across our diverse experiences, resonances and affinities sparked. Two people (or sometimes three or more) would begin to wonder what it might be like to write together with another particular person, around a certain theme or idea. We wrote about the wild liberation of wheelchairs, the claustrophobia of shopping centres, the dehumanising tendencies of hospitals. We riffed on shame, ambivalence, love and sensitivity. We speculated about a future where consultancies run by people with autism and disability would help non-disabled people amplify their otherness, rather than the other way round. We interrogated the history and future of medical research. We thought together about racism, misogyny and eugenics. We sat beneath trees.  Sensitive listening and speakingEvery collaboration, for us, was a painstaking exercise in listening and speaking. This unpredictable, uncontrollable, expansive process determined both the process and the outcome. It was shaped by the energies each writer brought to the encounter, which were in turn shaped by preoccupations, traumas, aspirations, sensitivities, aesthetic inclinations and curiosities. The most subtle, unforced collaborations sometimes resulted in poems in one coherent voice. The most intense, difficult collaborations sometimes led to two-column poems, with stark white space between them. This is as it should be. In any conversation, a burgeoning intimacy often makes our differences both more apparent, more significant, and yet also a little less obstructive. I know my ache is not your pain, which is not their suffering. Why do I think myself alone? I am trying to quieten this murmur in my bones, so I can listen. – Gemma Mahadeo & Andy Jackson, from the poem Awry In one collaboration, thinking of a spine that is not straight and a sexuality that is not straight, thinking of how we navigate public spaces differently and yet similarly, we each wrote a few lines of poetry each, until we had what felt like an entire poem. We then embarked on a process of editing, each time removing those elements of the piece that made it seem like two distinct voices. Our voices almost merged. I extend my hand-cane hybrid towards the ground in front of me like a diviner – this path, this body, not the only crooked things… We yearn for the possibilities of another city, another body as we fall, knee-first onto the blunt fact of queer promise. – Bron Bateman & Andy Jackson from the poem Betrayal In another collaboration, I was aware the other writer had experienced traumatic abuse, so I soon felt that when writing together – in a way that would not just be respectful but useful, for us both and for the poem – our voices would have to be distinct. To dominate or erase another’s words, even with good intentions or under some pretence of “improving the poem”, would have been precipitous ground. The poem we ended up writing together was composed of two parallel voices, two wings. The air around them, and between us, held us up. Assure child they are not at fault. Refuse to be absolved of blame. Find the subliminal rhymes. Broken as open. Other as wisdom. – Leah Robertson & Andy Jackson, from the poem Debris Rigour and careEach collaboration had its own particular questions and dilemmas. Each one required rigour and care, patience and courage. There were many awkward little stumbles and pauses. Yet the process was also profoundly liberating. It felt like someone had opened a window, so that a stifling room finally had air and outlook. My sense, too, was that with the windows flung open, those outside our world could see in, might begin to more deeply appreciate the innumerable ways bodies are marginalised. That readers of all kinds would see their own predicaments connected to ours. Disability as one dimension of injustice, a dimension that reminds us of the ground we share, flesh and earth. Disability as gravitational force.  There is something in the collective political and social atmosphere that suggests collaboration, working together, especially with people outside our usual circle, is either anathema or too difficult. Think of any of the crises that are front of mind at the moment – the dialogue around the Voice referendum and the fallout from its defeat , the fraught process of ensuring a just transition away from fossil fuels , the long histories and cycles of war and revenge across the globe. You could even include your own intimate cul-de-sacs of unresolved conflict. Corporate tech algorithms amplify our tribal attachments, assume and encourage our binarism, our quick, unthinking reactions. The blinkers are on, and are being tightened. This is not, to state the obvious, desirable or in any way sustainable. Perhaps this is why, in the last five to ten years, there has been an increasing number of collaborative writing projects. Against the tide of hesitation and mistrust, a felt need to work together, within and across identities.  I’m thinking of Woven , the anthology of collaborative poetry by First Nations writers from here and other lands, edited by Anne Marie Te Whiu. John Kinsella’s careful and ethical collaborative experiments with Charmaine Papertalk-Green, Kwame Dawes and Thurston Moore. Then there’s Audrey Molloy and Anthony Lawrence’s intensely lyrical and sensitive conversation in Ordinary Time . And Ken Bolton and Peter Bakowski’s four recent collaborative books , which contain an array of darkly humorous fictional and fictionalised characters. This is only the poetic tip of the iceberg of recent collaborations. Writers are one group of people who are tuning in to the need to go beyond the isolation or echo chambers. They know that the stories we are told – the need to be self-reliant and independent, the impetus to be suspicious of the other, or even that sense of inferiority that makes us feel disqualified from contributing – aren’t carved in stone. Or if they are, the persistent drip and flow of water can do its liberatory, erosive (and constructive) work. We have, after all, only survived as a species and as communities through collaboration and mutual support. Of course, we know there are countless collaborations currently being orchestrated by malicious agents: fascists, racists, misogynists, cynical corporate shills astroturfing against essential urgent climate action, even (to some degree) the reflexive social-media pile-ons. People are always working together in some way, deeply connected and inter-responsive. Collaboration in itself is not some utopian panacea. Disabled collaborationSo I want to suggest that only a particular kind of collaboration can be properly transformative, humanising and grounding. It’s a collaboration of deep attentiveness and mutual exposure: a way of being together in which we set our certainties and fears aside, to be present to the other, to allow the other to be themselves, and to be open to the otherness in ourselves, an encounter which sensitises us to the complexities and bodiliness of injustice. Let’s call it disabled collaboration. Let me explain. As a disabled person, you are constrained, walled out of important social spaces: there are only steps into the workplace, the performance isn’t translated, or the shop is non-negotiable sensory overload. Even if you do manage to enter these spaces, it is made clear to you that you don’t really belong. They might stare at you, or signal their discomfort with silence or overcompensation. (And, yes, the shift to second-person is deliberate.) Unless you give up – and which of us would not admit to giving up sometimes, or in some part of ourselves? – you spend a lot of energy proposing, asking, suggesting, pleading, demanding. You know what you need to be able to live a life of nourishment, connection, pleasure. You speak, in your own voice, out of your particular situation, from across the barriers. Perhaps disability is really essentially about this giving voice. About constantly having to express what is unheard – or perhaps sometimes unhearable – by the broader society.  This isn’t about transmitting thoughts or ideas. This is essentially a cry for connection, for help. For solidarity, allyship, change. What you’re after is collaboration: two or more people bringing their resources to bear upon a human situation, which may have fallen heavily on one person, but hovers over us all. Disabled people know this territory intimately. We regularly share much-needed information, resources, concern and time with each other. This kind of collaboration, by definition, cannot assume an equality of voice, mode of operation or capacity. It is predicated on learning about difference and then responding to it: whether through listening, care work, protest or support. This collaboration acknowledges and resists disadvantage, isolation and enforced voicelessness. It’s the kind of orientation towards another person that, I want to suggest, is exactly what might help us respond properly to the multiple, intersecting crises we find ourselves in. It’s a listening not only to the concerns and experiences of the other, but an ambition to adapt to their particular way of expressing themselves. To be clear, I’m not saying disabled people have any special talent for collaboration. We can be as bitter, isolationist, selfish or stubborn as any non-disabled person. In fact, there are aspects to being disabled that can encourage suspicion towards others, a scepticism that at times affords you the space to assess risk. Can I trust this person with my needs, my life? It’s a caution that is understandable, and useful, but it can also keep us isolated. The cycle of othering depends on those othered doing some of the work, thinking this is all I deserve , or the perpetual doubtful thought of “maybe next time”. On top of that, there are intersections of injustice that are particularly resistant. They don’t dissolve in the presence of collaboration, but require immense effort to shift. In facilitating this project, I found that the most stubborn dividing factors were class and race. There are individualist, neoliberal dynamics at the core of funding guidelines and in our lives generally. Writing and publishing remain fields still dominated by white, middle-class connections and aesthetics. When we sit down to write or work together, these things do not disappear. When writers are paid for their work, it does not mean the same thing for each person.  Throughout this project, I have asked myself a number of questions. How do I, as a funding recipient, ensure that my collaborators are not exploited or taken for granted? What assumptions do I carry, invisibly, about the merits of particular voices? Should I step back to give more space to Indigenous writers, culturally and linguistically diverse writers, queer writers? How do we speak together within a poem or essay in a way that reaffirms common cause without diminishing the very real differences? These difficult questions have not been resolved. Still, their intractability really only reinforces my wider point. We need to engage together in a way that is predicated on difference, exposure, vulnerability and mutual support. If disability is the imprint or shadow of bodily injustice, then collaborating in a disabled way, consciously, can radically expand our understanding of our shared predicament. What happens within the process of disabled collaboration is akin to the words in Sarah Stivens and Jasper Peach’s poem, Crack & Burn: Different bodies with the same fears, different aches with the same stories Our brains tell us that we’re alone, but we know not to believe them … When we gather in numbers it’s impossible to feel less than because all I see – everywhere I look – is raging grace and powerful repose. The experience foreshadows, in a small but potent way, the future we wish to live in. What might disabled collaboration achieve? The poem Coalescent, written by Beau Windon, myself, Michèle Saint-Yves, Robin M Eames and Ruby Hillsmith, suggests a hopeful answer: overturning the old regime of normalcy for something strange / / something glorious / / something new - Collaboration

- Friday essay

- Disability coverage

- Social model of disability

- New research, Australia New Zealand

Economics Editor Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Strategy and Services) Director and Chief of Staff, Indigenous Portfolio Chief People & Culture OfficerLecturer / senior lecturer in construction and project management. - More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of present (Entry 1 of 4) Definition of present (Entry 2 of 4) transitive verb intransitive verb Definition of present (Entry 3 of 4) Definition of present (Entry 4 of 4) - fairing [ British ]

- freebee

- largess

- presentation

- present-day

- here and now

give , present , donate , bestow , confer , afford mean to convey to another as a possession. give , the general term, is applicable to any passing over of anything by any means. present carries a note of formality and ceremony. donate is likely to imply a publicized giving (as to charity). bestow implies the conveying of something as a gift and may suggest condescension on the part of the giver. confer implies a gracious giving (as of a favor or honor). afford implies a giving or bestowing usually as a natural or legitimate consequence of the character of the giver. Examples of present in a SentenceThese examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'present.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples. Word HistoryMiddle English, from Anglo-French, from presenter Middle English, from Anglo-French presenter , from Latin praesentare , from praesent-, praesens , adjective Middle English, from Anglo-French, from Latin praesent-, praesens , from present participle of praeesse to be before one, from prae- pre- + esse to be — more at is 13th century, in the meaning defined above 14th century, in the meaning defined at transitive sense 3b(1) 14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1 14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 3a Phrases Containing present- all present and accounted for

- all present and correct

- at the present time

- co - present

- historical present

- present arms

- present company excepted

- present company excluded

- present - day

- present oneself

- present participle

- present perfect

- present tense

- present value

- present writer

- re - present

- the present

- the present day

- the present perfect

- the present writer

- there's no time like the present

Articles Related to present We Got You This Article on 'Gift' vs.... We Got You This Article on 'Gift' vs. 'Present'And yes, 'gift' is a verb. Dictionary Entries Near presentpresentable Cite this Entry“Present.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/present. Accessed 28 Sep. 2024. Kids DefinitionKids definition of present. Kids Definition of present (Entry 2 of 4) Kids Definition of present (Entry 3 of 4) Kids Definition of present (Entry 4 of 4) Medical DefinitionMedical definition of present, legal definition, legal definition of present. (Entry 1 of 2) Legal Definition of present (Entry 2 of 2) More from Merriam-Webster on presentNglish: Translation of present for Spanish Speakers Britannica English: Translation of present for Arabic Speakers Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about present Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!  Can you solve 4 words at once?Word of the day. See Definitions and Examples » Get Word of the Day daily email! Popular in Grammar & UsagePlural and possessive names: a guide, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, the difference between 'i.e.' and 'e.g.', more commonly misspelled words, absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, weird words for autumn time, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), 9 superb owl words, 15 words that used to mean something different, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, games & quizzes.  Transition your wardrobe with fall sneakers, chore jackets, more stylist picks — from $16  - Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Concert Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today More Brands I was a middle schooler with HIV. This teacher’s kindness changed meThe following essay was excerpted from Upworthy’s “ GOOD PEOPLE ,” by Gabriel Reilich and Lucia Knell, available now wherever books are sold. I received my death sentence at 2 years old, with 11 years to live if I was lucky. I took 36 pills every day, crushed into food and drinks, hoping it would give me more time. A guinea pig for new treatments, I spent more time in the hospital than I did on the playground. I was too little to understand that my childhood deviated from the norm. If you’d asked me at that age, “Hey Lexi, what’s it like to be sick?” I wouldn’t have had an answer — sickness was all I’d ever known. It’s like that joke about the fish. You ask the fish, “How’s the water today?” The fish replies, “What’s water?” At 4 ½, I lost my mother to the same virus I had — the same one she unknowingly gave me. Her death was a drop in the water in which I swam — a drop so charged and potent it changed the color of my world.  Shortly after this, I started kindergarten. When the harsh reality of my illness hit full force, she wasn’t there to help me swim. At school, during nap time, I wasn’t given pillows or blankets, or allowed to sleep near the other kids. Staff laughed at me while I put my legs through my jacket sleeves to stay warm. In first grade, if I spit or bled, I was sent home. I had my own bathroom, and was relegated to the far corner of the classroom. You see, I wasn’t just ill with a typical cold or flu; I was ill with an invisible virus everybody feared. My first lesson in school was this: You, Lexi Gibson, are not a kid to be loved. You are something unknown, something to be feared. Middle school was a nightmare; bullying was on the daily agenda. Most of the time, no one sat with me during meals; I’d say I felt invisible, but it was actually quite the opposite. I was the laughingstock of the school, routinely shoved back and forth between people, all of whom jeered while calling me names. Paper wads and pennies were thrown at me during class. The day I died inside had to be the afternoon I showed up to science class to find huge scrawled letters on the door: Lexi has AIDS. Usually when a person has a terminal illness, they’re met with empathy and love. But my HIV diagnosis provoked ridicule and loathing.  In seventh grade, though, I got lucky: Mrs. Marks was my science teacher. She was the only person in the whole school to treat me like a normal human being. She was the oxygen to my water, and didn’t allow anyone to bully me under her watch. Funny and bright, she wasn’t charismatic in a showy way, like a teacher in a movie who stands on a desk. She was grounded and empathic. She was real. So, one day, at lunch, instead of signing up for another round of human target practice, I walked into her classroom and asked, “Could I eat with you?” She said, “Sure” — like a person who’d actually enjoy my company. After that day, her classroom became my safe haven. I don’t think we talked about it, the bullying. But I knew she knew. She was one of those people, capable of unspoken understanding. Nothing momentous happened in that classroom; that’s what made it special. Mrs. Marks and I would sit and talk, watch movies or listen to music. Sometimes I’d draw or do homework. Sometimes we’d sit and be quiet, and it wasn’t awkward; it was revelatory. You see, in the water I swam in, chaos was the norm. At home, at school — people yelling, slamming doors, beating me, screaming insults. Even louder than that was the noise inside my head: the internalized mean girl on a loop. The one who told me without hesitation that I was worthless, a freak, unwanted and impossible to love. I believed what everyone told me. But when I ate lunch with Mrs. Marks, for 50 minutes, the noise went away. For the first time since my mother died, I experienced something deeper than quiet. I experienced peace.  Abandoned by my father at 14, I found myself on my deathbed at 15, my organs shutting down. My adoptive mom (another story) fought hard to get me into a medical study with new medication that would “hopefully” save my life. I wasn’t hopeful. I’d been in studies my whole life. Hope required energy I no longer had. But I was wrong. This time, the drugs worked. My viral count dwindled until it virtually disappeared. Undetectable, they called it. I won’t say it was a miracle and risk undermining the collective effort of thousands of scientists who dedicate their lives to making things like this possible. But I will say it felt like one. I’m not going to lie. My problems didn’t just go away; there’s no drug you can take for that. A lifetime of being treated like an untouchable takes its toll. And it takes a truckload of therapy to convince yourself that you are not, in fact, a virus; you are a human worthy of love. Deserving of happiness, health, hope — all the h words that aren’t “HIV.” At 31, I live in Las Vegas and own a beautiful ranch home on a half acre. I am surrounded by people who love and accept me — people like Mrs. Marks, who provided proof of kindness when I needed it most. The serenity I experienced in her classroom, once so rare, is now boundless. Drop by drop, I changed the water I swim in — from gloomy and turbulent to calm and clear. Love and belief are all I needed. After all, I know how precious life is; not a day goes by without gratitude to see another sunrise. If you ask me now, “How’s the water today?” this time, I have an answer. The water is beautiful. Lexi Gibson's story is featured in Upworthy’s “ GOOD PEOPLE ,” by Gabriel Reilich and Lucia Knell, available now wherever books are sold. Synonyms for This presents86 other terms for this presents - words and phrases with similar meaning. Alternatively  |

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Find 120 different ways to say PRESENTS, along with antonyms, related words, and example sentences at Thesaurus.com.

Synonyms for PRESENTS: offers, gives, carries, stages, performs, shows, displays, mounts; Antonyms of PRESENTS: holds, keeps, retains, preserves, saves, lends ...

Synonyms for PRESENT: offer, give, stage, carry, perform, show, mount, display; Antonyms of PRESENT: keep, hold, retain, withhold, preserve, save, lend, advance

Synonyms for presents include shows, displays, exhibits, airs, demos, parades, produces, showcases, unveils and brandishes. Find more similar words at wordhippo.com!

Synonyms for present include existent, immediate, current, existing, extant, instant, ongoing, prompt, breathing and commenced. Find more similar words at wordhippo.com!

PRESENTS in Thesaurus: 1000+ Synonyms & Antonyms for PRESENTS. Thesaurus for Presents. Related terms for presents - synonyms, antonyms and sentences with presents. thesaurus.

Another way to say Presents? Synonyms for Presents (other words and phrases for Presents).

PRESENT - Synonyms, related words and examples | Cambridge English Thesaurus

The sunburst logo (🔆) is the emoji symbol for "high brightness", which we aspire to create with OneLook. (The graphic came from the open-source. Synonyms and related words for presents from OneLook Thesaurus, a powerful English thesaurus and brainstorming tool that lets you describe what you're looking for in plain terms.

Find the best synonyms and antonyms for PRESENT with examples and definitions. Explore the power of words with Power Thesaurus.

Synonyms for PRESENT in English: current, existing, immediate, contemporary, instant, present-day, existent, extant, here, there, …

9. Likewise. Usage: Use "likewise" when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you've just mentioned. Example: "Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.". 10. Similarly. Usage: Use "similarly" in the same way as "likewise".

presents - WordReference thesaurus: synonyms, discussion and more. All Free.

Synonyms for PRESENTS: gifts, temporalities, grants, gratuities, donations, presentations, intimates, faces, represents, alleges, lays; Antonyms for PRESENTS: takes ...

Current is an excellent synonym of present. Current indicates that something is occurring, being used, or being performed at present. The term 'current' means 'anticipated to occur within a year or less.'. Current denotes "presently in effect" in the mid-15c. It meant "prevalent, generally reported or known" in the 1560s and ...

Synonyms for PRESENT: contemporary, now, existing, immediate, instant, being, in process, in duration, begun, started; Antonyms for PRESENT: past, over, completed ...

Argumentative essays. An argumentative essay presents an extended, evidence-based argument. It requires a strong thesis statement—a clearly defined stance on your topic. Your aim is to convince the reader of your thesis using evidence (such as quotations) and analysis.. Argumentative essays test your ability to research and present your own position on a topic.

64 other terms for present something - words and phrases with similar meaning. synonyms. antonyms. definitions. sentences.

I am writing many essays in preparation for my English Literature GCSE. I keep using the same words (presenting, showing, implying, conveying, portraying) to say how the author presents a character. Can anyone think of any other words I could use instead of these? Thank you. 0 Report. Reply. Reply 1. 7 years ago. username2552331. 13.

Synonyms for PRESENTED: offered, gave, carried, staged, performed, mounted, displayed, exhibited; Antonyms of PRESENTED: held, retained, kept, withheld, preserved ...

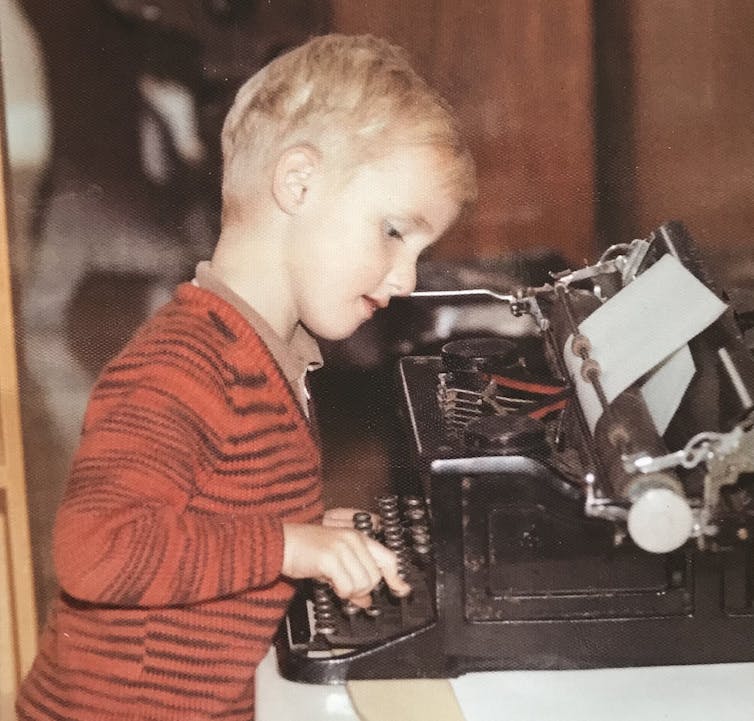

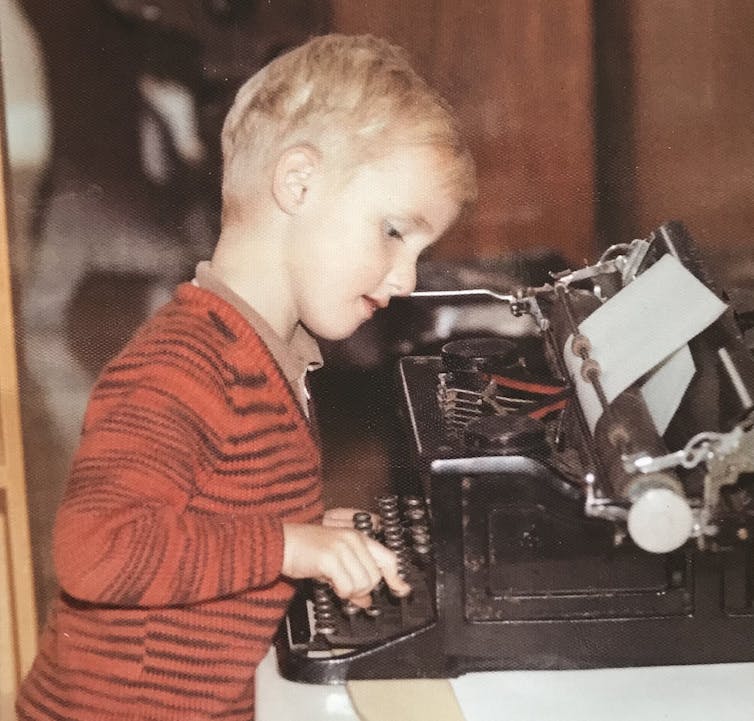

Andy Jackson at kindergarten. Andy Jackson. My sense back then was that disability was about impairment. They use wheelchairs. They're blind or deaf.

The meaning of PRESENT is something presented : gift. How to use present in a sentence. Synonym Discussion of Present.

The following essay was excerpted from Upworthy's "GOOD PEOPLE," by Gabriel Reilich and Lucia Knell, available now wherever books are sold. I received my death sentence at 2 years old, with ...

Synonyms for This presents. 86 other terms for this presents - words and phrases with similar meaning. this exhibits. v. this represents. v. this conveys. v. this shows.